In December last year, Patrick Kaczmarczyk and I pointed out that even 20 years after the great currency drama in Argentina, neither the country nor the international community have found a way to bring the Argentine economy back to a normal path. Now Argentina has received a new loan of 45 billion US dollars from the IMF (International Monetary Fund, here is the IMF press release) and, there is no other way to put it, the drama is starting all over again.

If one looks at the figures provided by the IMF in its detailed Country Report, one is inclined to ask whether this institution has existed in this world for the past fifty years or whether it has perhaps been shunted out into space for a few decades, so that all the important changes that have happened even in the mainstream doctrine of economics have completely passed it by.

Argentina: A hopeless case?

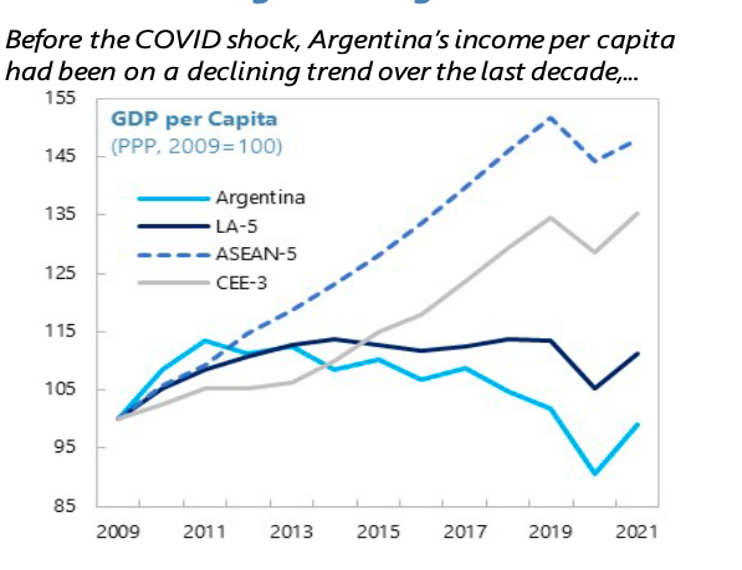

The economic situation in Argentina can easily be characterised in a few sentences. GDP per capita has fallen almost consistently since 2011 (Figure 1 from the IMF report, which includes five other Latin American (LA-5), five Asian (ASEAN-5) and some Eastern European countries (CEE-3) for comparison). This is more than dramatic, this is catastrophic. Official unemployment is over ten percent and the poverty rate, even as reported by the IMF, is over 40 percent. The inflation rate is currently hovering between 40 and 50 percent, as it has been for several years. The short-term interest rate is currently around 40 per cent and the Argentine peso has recently depreciated drastically against Western currencies.

Figure 1

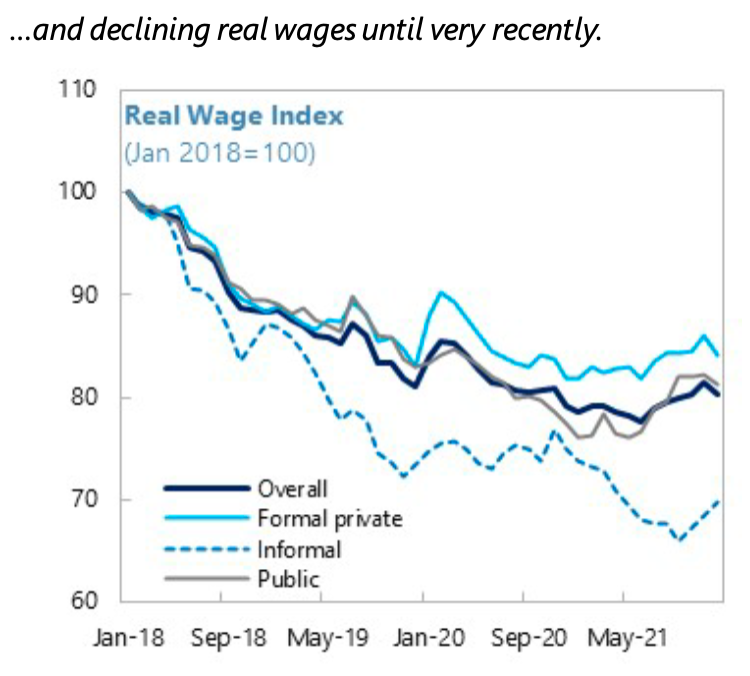

The fact that average real wages fell by almost 20 per cent between 2018 and the summer of 2021, which can also be read from the IMF report (Figure 2), says more than anything else.

Figure 2

What can be done in such a situation? Well, the IMF, in its programme up to 2027, which the Argentine government has agreed to, concludes that one must now be disciplined, grit one’s teeth, cut public spending to reduce government deficits, align monetary policy with a money supply (the monetary base should be 7.5 per cent of GDP over the entire period and M3 should also have a stable ratio of 3 per cent to the base) and one will halve inflation by 2027 and achieve positive growth rates every year.

The IMF is mentally stagnant, even if it uses some modern words.

This is obviously nonsense. First, it is monetarist nonsense that has been practised by the IMF for many decades, even though this doctrine has not been applied by central banks in the Western-Northern world or seriously taught at universities for at least two decades. The Argentine central bank, like all other central banks in the world, can only control interest rates and the IMF should have been explicit about this. But it “elegantly” circumvents this by pretending that the central bank can simply keep the money supply ratios constant in times of high inflation.

For the state to cut its spending at a time when the economy has not yet regained its footing after an extremely long recession (and, given the basic economic conditions, will not regain it either) is classic austerity policy and thus absurd from the outset. The intellectual obsolescence of the IMF is also shown by the fact that it has obviously not heard of sectoral fiscal balances and is therefore not in a position to analyse the government balance in this framework and to draw adequate conclusions for fiscal policy. Since it is not to be expected that private investment will pick up in Argentina any time soon, any attempt by the state to reduce its deficits independently of the rest of the economy is doomed to failure.

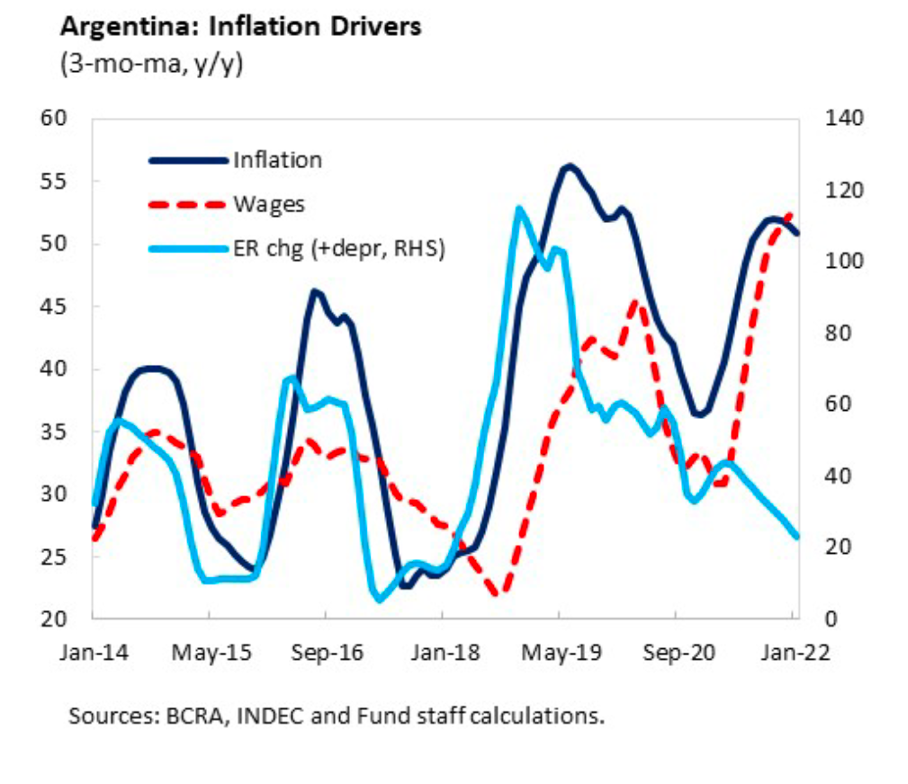

What is more than astonishing, however, is that one can use evidence found in the report itself to show why the IMF solution is completely out of the range of the reasonable solutions. The IMF itself identifies wages and the exchange rate, or the devaluation phases of the Argentine currency, as the decisive drivers of high inflation. (Figure 3, where the devaluation is plotted on the right-hand scale and positive percentages indicate a devaluation, even if the devaluation, as recently, is smaller).

Figure 3

Any sensible observer, looking at this picture, would have immediately said, sure, Argentina, like so many countries before it, obviously is suffering from a system of wage indexation based on past inflation rates (the so-called backward-looking indexation made famous by the Italian “scala mobile” of the 1970s and 1980s). And indeed, the Fund notes in its report that such indexation exists in Argentina.

Any observer who knows a little about the history of the scala mobile could have immediately told the Fund’s staff that it is completely pointless to keep fighting this indexation with restrictive monetary and fiscal policies, but that one has to do what Italy did in the 1980s, namely to convince its own trade unions that such a system is counterproductive and above all systematically harms the workers because it always leads to new bouts of unemployment. After all, indexation in Argentina did not even prevent the huge collapse of real wages.

But who is supposed to know something like that in the IMF today? Apparently not even the Italian Executive Director who, like all the others (including the German one), agreed. Mario Draghi (who worked under Carlo Ciampi, the brave fighter against the scala mobile) would certainly have known, but he has certainly not been involved.

The IMF staff, when reviewing the literature of past disinflationary periods, even mention Israel, where income policies have been successful. But it does not occur to them to make this insight the core of their recommendations. Incomes policy is mentioned, but only as “complementary” in the fight against inflation, because the experience with it is “mixed” and it must be accompanied by a good macroeconomic concept. This is exactly the wrong way round: there can only be a good macroeconomic plan if indexation is eliminated, and income policy is pursued consistently.

What can Argentina do?

In order to free itself from the inflation trap, Argentina must first of all end wage indexation. But this can only be done in a deal with the trade unions, in which the government explicitly commits itself to do everything possible to stabilise real wages and especially the real wages of the lower wage groups. To be successful, the government must make it clear to employers that the time of high inflation rates is over and that wage negotiations with the trade unions (under strict control by the government) will take place on a new basis, namely mutual respect for the moderate inflation target announced by the government (plus the central bank).

Argentina can only escape inflation and at the same time normalise its economic development and employment levels if it is clear to all parties that government-orchestrated incomes policies are unavoidable. Which ultimately means guaranteeing workers full and systematic participation in productivity gains. But the IMF can never recommend this, because it would violate the most sacred law of neoclassicism, the flexible wage (cf. this paper).

Only if income and inflation are secured by the state can the central bank set the interest rate in such a way as to stimulate investment. The interest rate could immediately be lowered from its high level to a rate that is below the expected nominal growth rate, i.e. clearly in the single digits.

The Argentine deal would have to be secured, and here lies the real task of an institution like the IMF, by an external economic regime in which the international community helps the country to defend its exchange rate against speculative attacks and to stabilise its real effective exchange rate.

However, a solution in Argentina as elsewhere can only be found without the age-old IMF: As long as the country depends on money from the Washington bureaucracy, controlled by Western diplomats who would never go against the prevailing orthodox doctrine in economics, there is simply no way out. One can already predict that Argentina has more difficult years ahead. The devaluation of its currency may provide a boost to exports and thus some relief, but the country is miles away from a concept that would allow it to offer a positive perspective to the mass of the population and reduce poverty.