Inflation continues to be on everyone’s lips. At 7.4 per cent, a rate was reached in April this year that is almost unique in the history of the Federal Republic of Germany. Only in the early summer of 1973, around the turn of the year 1973/1974 and in October 1981 was the rate of increase in the consumer price index higher than at present. The pressure on the ECB to respond with interest rate hikes is growing daily. At the same time, the proponents of a tighter monetary policy fail to provide a plausible explanation as to how and with what macroeconomic consequences interest rate hikes can bring the current price increases for imported commodities to a halt.

In order to better understand what is currently happening with prices, one needs to look closely at the empirical evidence and have a clear idea of the processes in a market economy. Only then it is possible to assess what the consequences of a reversal in monetary policy would be and what wage policy should and should not do. The representatives of both policy areas, the wage bargaining parties and the central bank, are, in fact, important actors in macroeconomic terms who exert a major and mutually dependent influence on the course of nominal and real economic development.

The foreign policy shocks and natural disasters that have hit and will hit Germany and Europe are beyond the control of either policy area. But how these shocks are dealt with, whether the forces of the market economy are used wisely to absorb the shocks or whether the shocks are exacerbated by misconduct on the part of one and/or the other policy area, is decided by the representatives of wage and monetary policy, and they bear responsibility for this. Fiscal policy, for its part, can and should be supportive in terms of cushioning social hardship, but it cannot make up for mistakes made by monetary and wage policy.

Producer price increases as a precursor to the great inflation?

There is concern that today’s price development is more dramatic than the inflation of the 1970s because producer prices are currently rising many times faster than they did then. Since producer prices are a harbinger of inflation at the consumer level, one must assume that consumer prices will follow suit and consequently inflation will be much higher than then. What are we to make of this argument?

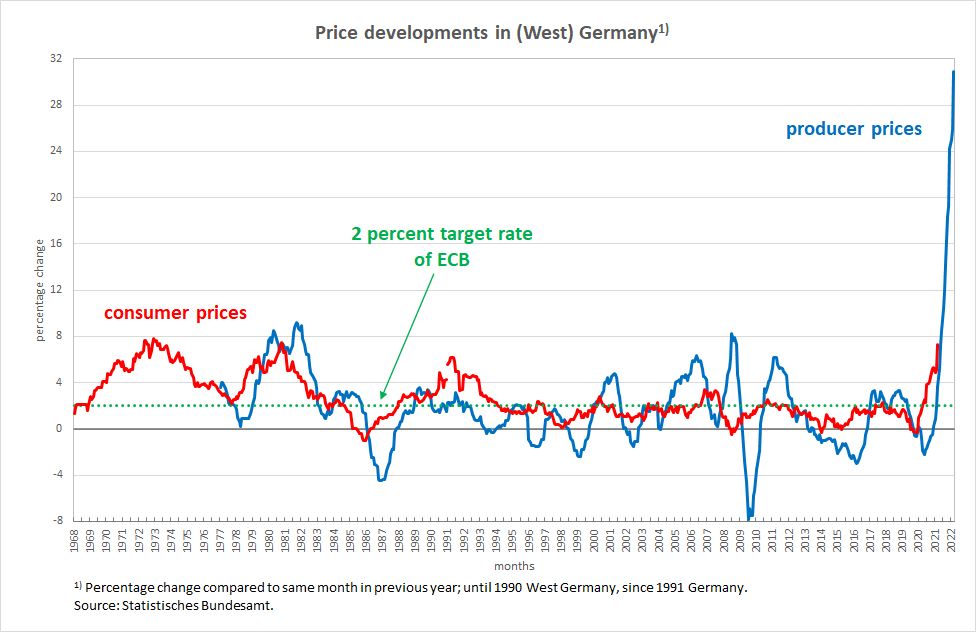

Figure 1 shows how big the discrepancy is between then and now in terms of producer price increases. At the beginning of the 1980s, the price increase at the producer level was about nine percent. Since July 2021, the growth rates have been in double digits for the first time and have reached 31 percent by March 2022.

Figure 1

The graph also shows very clearly that producer prices and consumer prices have never moved as far apart as they have this time since the late 1970s. This suggests that the process is different today than it was then and that comparisons with the inflation trend and monetary policy of the past are therefore of little use.

Let us assume that in a country (as just shown in the case of Argentina) there is an inflation rate of 50 per cent that has been going on for several years and simply does not want to disappear. There, no one can say anymore exactly what the inflation (from Latin inflare = to inflate), i.e. the “inflating” of prices on a broad front, is due to in detail. Practically all prices are rising sharply, both those at producer level and those at consumer level. This is what is meant by undesirable inflation: a process of sharply rising prices that no longer has any clearly identifiable causes in the sense of specific real shortages, but which comes about and continues as a result of mutually accumulating price and wage increases. Even if there was a triggering factor at the beginning of this process, it is no longer relevant because the process has taken on a life of its own.

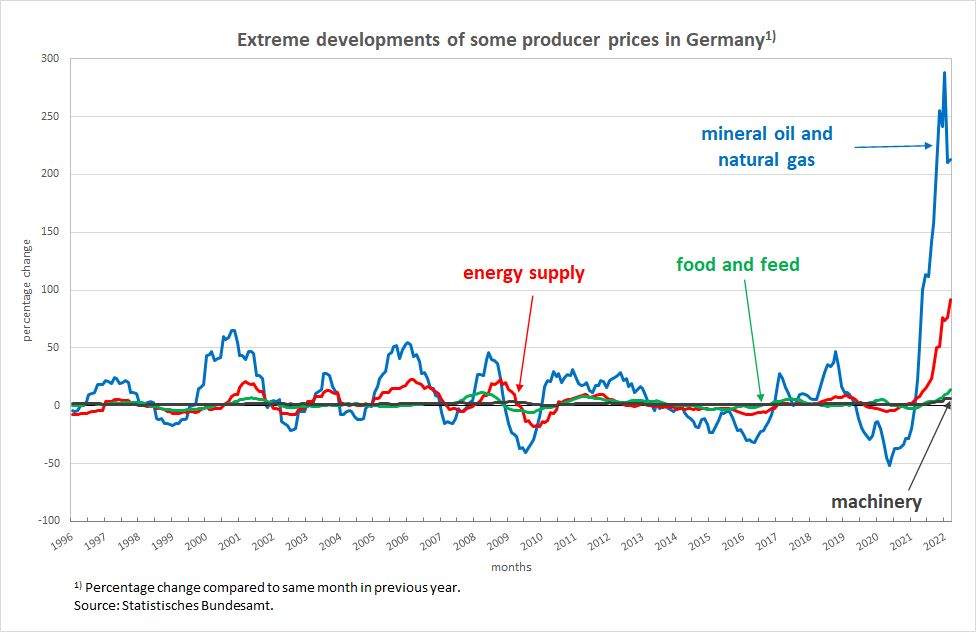

What kind of process is currently taking place in Germany (and in Europe as a whole)? Are more or less all prices rising for no apparent reason and on a similar scale? No, they are not. The decisive cause of the high price increases at the producer level are, as Figure 2 shows, extreme price increases for very specific (pre-)products, namely natural gas and crude oil, which drove the price index for energy supply up by an enormous 91 percent in March.

Figure 2

And since energy is an intermediate product that is involved in virtually all manufacturing processes of goods, this price increase eats into the producer prices of many other goods. But – and this is the important point – it does not do so on the same scale as the energy price index, because goods require different amounts of energy to produce. Accordingly, only a part of their production costs rises sharply.

There are also shortages of other intermediate products, such as certain foods or certain metals, which have to do with both supply bottlenecks and specific surges in demand. But here, too, price developments – as long as they are not primarily speculation-driven – signal real processes that do not have to do with an indiscriminate explosion of prices and incomes across the board, as would be the prerequisite for a self-reinforcing inflationary spiral.

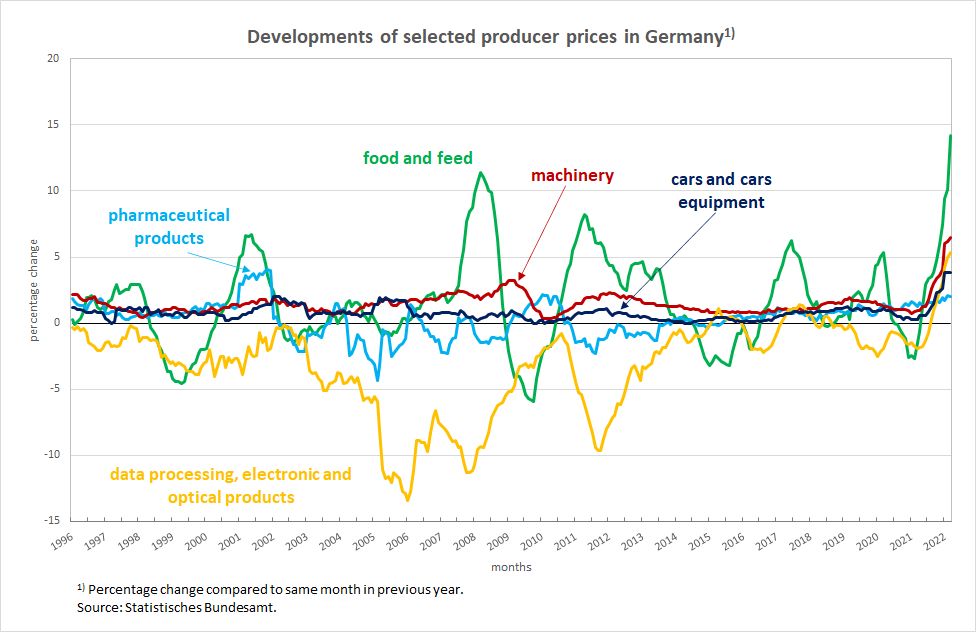

Figure 3 illustrates the relationship for some products: Whereas in earlier years the price developments of various goods diverged strongly from each other, the current margin shows a certain synchronisation: the direction of many individual producer prices is upwards, but the dimension of the increase is very different.

Figure 3

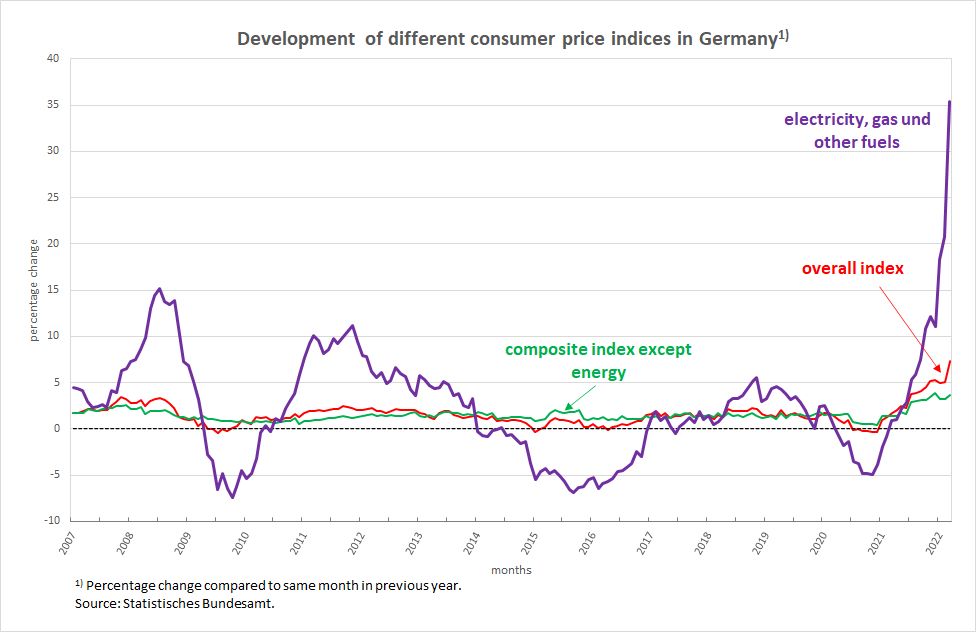

And this also affects the development of different consumer prices differently. Figure 4 shows how strongly the extreme price increases at the producer level for natural gas and crude oil of almost 300 percent affect the consumer price index for electricity, gas and other fuels, namely with a plus of 35 percent, and how much this pulls the overall consumer price index up, namely to over 7 percent. Without the energy bundle of goods at the consumer level, the index is up 3.6 percent in March. This means that the prices of the remaining goods at the consumer level have so far by no means taken on a development that could be described as inflationary, despite the energy price surge and other bottlenecks such as the corona-related disruptions of global supply chains.

Figure 4

The question is whether they will do so in the future.

Will the causes of the current rates of price increases persist?

There are three main causes of the current price increases: There are corona-related supply bottlenecks in world trade, which lead to shortages and thus to price increases because of internationally strongly interlocked production chains. They will decrease again as the pandemic situation eases and as a reaction to these trade problems in the medium term a shift of production back closer to the end consumer might occur (keyword de-globalisation). How quickly and extensively both will happen is difficult to predict. But it is in the nature of things that price pressure from this side cannot be expected to last indefinitely.

The second cause is the war in Ukraine. It is leading to supply and production bottlenecks for Ukrainian exports (grain and grain products) and to a shortage of raw materials from Russia caused by mutual sanctions, especially fossil fuels, but also metals. Since both countries cover significant world market shares with their respective production, the decline in supply quantities cannot be compensated for by other suppliers in the short term, or only to an insufficient extent – noticeable price increases for these goods are the result. In addition, the expectation of such shortages contributes to hoarding and financial speculation, which fuels the real shortages and price increases – a self-fulfilling and reinforcing forecast. Since, on top of that, it is a question of intermediate products that are used as inputs in various final products, the rising costs pave their way up to the consumer prices in the affected product groups.

With regard to this cause, too, time horizons for the continuation or even aggravation of shortages can hardly be estimated. However, the state or the community of states should do everything possible to stop speculation on financialised markets, which is usually easy to do, but is usually successfully thwarted by the lobbyists. Windfall profits based on oligopoly structures (e.g. refineries) must be taxed. For if price developments no longer correctly indicate real scarcities, but are based to a significant extent on speculative bubble formation and incomplete competition, this leads to misallocations, harms many people active in the real economy and, conversely, rewards speculators and oligopolists.

One must always bear in mind that there are not only losers but also profiteers from price increases. After all, the increased money paid by input consumers and end users ends up in the coffers of others. This is true even if, in sum, the real cake becomes smaller for everyone because individual groups manage to increase their share of the shrinking cake so much that, in absolute terms, they have more than before.

The third cause of the current price development is the structural change caused by pandemic, war, climate crisis and the urgently needed efforts to protect the climate. When many people simultaneously demand e-bikes, timber, solar panels, energy consultants, electricians and landscape gardeners, for example, the corresponding industries reach their capacity limits in the short term, which drives up the prices that can be enforced there.

This effect – unlike speculative exaggerations and oligopolies – is entirely desirable. In this way, prices signal to consumers what they should use sparingly or what they should substitute if possible. The suppliers, in turn, are signalled what to produce and which resource-saving production technology is particularly worth inventing and using. As a result, price increases reduce shortages in the medium to long term by pushing back demand and promoting an expansion of supply. It is precisely in this mechanism that the strength of the market economy lies. Preventing rising prices through state intervention is therefore counterproductive.

However, the state can and should directly help those in society for whom rising prices for energy and e.g. food are an existential threat because they have no alternative, cheaper products and have such a low income that their budget was already exhausted before the prices for basic necessities rose. Such state aid is not guaranteed with the measures currently adopted, because they again aim far too one-sidedly at a general relief of consumers.

What can monetary policy do?

The first two causes of the current price increases are external to the German or European economy (apart from speculation). They are linked to a redistribution of real incomes away from the commodity consumers to the commodity suppliers. There is no way around this realisation: If things – for whatever reason – actually become scarcer, the market conditions shift in favour of the suppliers. If they come from abroad, real income migrates there. A tighter monetary policy cannot prevent this.

However, by raising interest rates, it can make it more difficult to initiate helpful production changes to eliminate the shortages. For these practically always consist of physical investment. Once again it becomes clear that the failure to put strong reins on the financial markets has negative consequences for the real economy. For of course, all the money that is available on the financial markets due to the loose monetary policy seeks its way into all kinds of investment forms, which primarily include speculative ones – be it gold, metals, food or other commodities. If this is to be curbed by making credit more expensive, i.e. by raising interest rates, this general remedy will affect all investment projects, even those investments in fixed assets that are now needed even more urgently than before the war.

Monetary policy should therefore only tighten the reins if the other decisive policy area, wage policy, forces it to do so by setting an inflationary process in motion. This would indeed cause massive damage to the entire European economy for years to come and must be prevented at all costs. Taking the precautionary position of monetary policy now, instead of entering into an intensive dialogue with the trade unions throughout Europe, would be the wrong way to go. The developments after the second oil price crisis at the end of the 1970s have shown this.

What about wages?

If the state takes on the task of relieving the burden on lower incomes, wage policy can support this with agreements that aim in exactly the same direction: significantly higher increases for the lower wage groups and standstill for the upper ones. Overall, i.e. for the total volume of the deal, there is nothing to gain for the unions in the case of scarcity-related price increases. Any additional average wage increases beyond the golden rule will be passed on by the companies in prices. And then there is the threat of real inflation, i.e. price increases on a broad front, which the central bank will fight very quickly with high interest rates and which will inevitably lead to rising unemployment.

One wonders why the chairman of the DGB, from whom nothing has been heard for years on the subject of appropriate wage policy, is now of all times rushing ahead and pretending that wage policy must now be realigned. In the last two decades, the DGB has not even been able (and apparently not willing) to ensure that workers have received the full nominal wage increases to which they are entitled at all times, amounting to the average productivity increase plus two per cent target inflation set by the ECB. To pretend now that the unions must ensure compensation for much higher price increases in collective bargaining, for which German employers are largely not responsible, is not very credible and would only fuel the looming economic malaise.

The desire to virtually undo real shortages by simply increasing all nominal wages must fail. For then an inflated nominal demand meets the same real shortages and inevitably leads to new price surges. In a market economy, the distribution struggle for goods that have become scarcer in real terms is conducted via prices. The only appropriate help that can and must be given to those on the lowest incomes in this struggle is a redistribution from top to bottom. This is where the trade unions should get involved and make it clear to the high earners that it is primarily they who have to pay the bill for the shortages, so that the current price surge does not turn into sustained inflation and a massive recession.

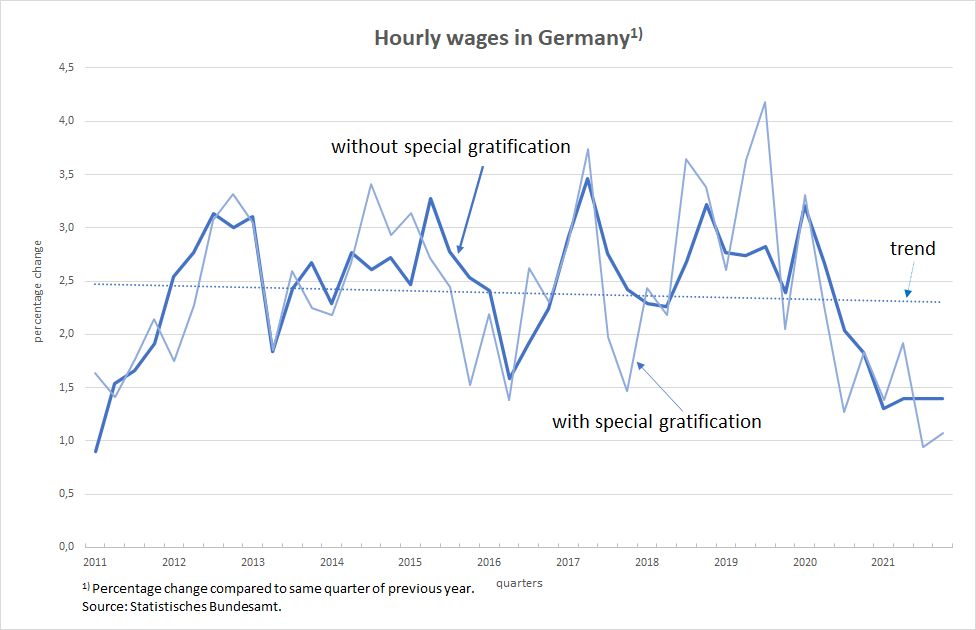

German collectively agreed wages have developed very moderately over the past ten years (Figure 5). There are good reasons to say that this has been too moderate in the EMU context (as shown many times, including in book “Against the Troika”). Consequently, a reversal in the sense of a truly productivity-oriented development or even above it would be absolutely appropriate. But jumping from one extreme to the other and now creating the impression among trade union members that there is something to be gained just now only shows that the top functionaries of the German trade unions are not up to date.

Figure 5

A look at the development of labour costs in Europe as a whole over the past year shows that there is still no inflationary pressure from wages: the labour cost index in the EU rose by an annual average of 1.7 per cent in 2021 – with a slight upward trend, i.e. by 2.3 per cent in the fourth quarter. In the EMU, labour cost growth was even lower than in the EU at an annual average of 1.2 per cent, also with a slight upward trend (1.8 per cent in the fourth quarter).

However, a look at the average annual increase in individual countries such as Poland (7.8 per cent), Bulgaria (7.4 per cent) and Romania (7.2 per cent), but also in some Eurozone member states such as Lithuania (12.0 per cent), Estonia (6.4 per cent) or Slovakia (5.3 per cent), all of which show a strong upward trend, shows how urgent it is to coordinate monetary and wage policy throughout Europe. The forces of the market economy to cushion the current shocks cannot have a meaningful effect if there is no cooperation between the major economic policy actors, but instead, for ideological reasons of a neo-liberal belief in the market, each area fights for itself and thus massively increases the problems.

In a new article in the not too distant future, we will take another detailed look at wage developments in the EMU and in the countries whose currencies are pegged to the euro.