Catastrophic events can carry the seeds of fundamental improvement. Thinking beyond the day, it is clear that a future peace can only be permanently secured with new concepts. Perhaps the West, and Europe in particular, will now finally learn that this requires much more than open markets.

After thirty lost years, the former transformation countries have a right not to continue to be regarded as appendages of the West – which, by the way, applies in the same way to the developing countries. Anyone who believes that it would be enough to simply offer them the opportunity to join the West completely, which means subordinating themselves to the West’s previous concepts without any ifs or buts, was wrong thirty years ago and is wrong today. This cannot be concealed by the currently so generously used concept of freedom, which in the narrower economic sense primarily conceals the dogma of free trade and the free movement of capital.

“Change through trade” at an end – but where was the beginning?

The current conflict between Russia and Europe shows, according to EU Commission Vice-Chairman Frans Timmermans (quoted here), that the concept of “change through trade” has failed. True. But it failed not because a better principle had been applied in the meantime or even because the old system conflict had broken out again, but because the trade that the West, including the EU Commission, offered to all transition countries was a sham.

There was simply too little change because the trade was the wrong one, i.e. it hindered the change that was actually necessary and desirable. After the fall of the Iron Curtain, the improvements that had been loudly promised by Western advisors and “partners” did not materialize in the countries of the former Eastern Bloc. This has created frustration among the population in these countries and brought politicians to power who question the model of change through trade and insist on their national interests. The EU Commission should know this better than others, since it deals with such politicians from its own member countries on a daily basis. The dispute between the EU Commission and Poland and Hungary over the rule of law before the European Court of Justice shows this more than clearly.

But how does Frans Timmermans want his sentence to be understood? If he thinks that the door of the exchange with Russia must now be permanently slammed shut because the exchange has not brought the desired success in terms of democracy and peace, he is making a big mistake. For in doing so, he is slamming the door on a real partnership, a partnership at eye level between the West and this great country. This partnership is the only key to lasting peace. Or do we want to build a wall around Russia to seal off this country from the Western world for the next hundred years? Would that bring lasting stable peace in Europe?

After the failed planned economy, the market economy is now facing failure

The West did not know what to do with the end of the Cold War in 1989 – it wanted and made money from it. What kind of cold war do we want to fight now? One between commodity producers and their customers? One between the privileged, who have always been privileged, and those who never will be under the current rules of the game? We already have this war within our own countries. Do we want to intensify it again on the international level, where the privileged have always won so far, instead of finally following our own centuries-old slogans about equality and equal rights?

The President of the EU Commission has rushed ahead with her sentence “We want them [Ukraine, author’s note] in the European Union” without having a long-term sustainable concept. The lack of such a concept can be seen, on the one hand, in the situation of the states of Southeastern Europe that have already been admitted to the EU. On the other hand, the admission of Ukraine to the EU would mean that Russia’s western borders would be almost continuous with EU countries. This would require, a fortiori, a plan for cooperative dealings with this large country, no matter who is at the head of the state there. Otherwise, Europe would find itself in a permanent tit-for-tat position or worse, but certainly not in a stable peace.

Conceptually, the large EU member states must make it clear to the Commission that membership in the European single market must not be the central goal of European cooperation. The single market in its current state already overtaxes countries like France or Italy. How, then, is an Eastern European country supposed to cope with it? Germany – like the Netherlands – has perverted the basic idea of the single market, namely to be a completely open market for equally strong companies and equally strong regions, with its mercantilism and its enormous current account surpluses, which have been accepted by the Commission for years.

Freedom and prosperity for all do not come through free markets everywhere

Trade between nation states that have independent governments must never become a one-way street. This applies to the global balances of exports and imports, but it must also apply to the corporate structures with which each country faces up to international trade. No country should simply sacrifice functioning industrial and technological structures to the international division of labor. After all, they are crucial to the future prospects of the respective populations because they represent the only source of material prosperity, namely progress in productivity. So as not to be misunderstood: This is not about platitudinous “growth,” but about positive technological development, which is also and especially necessary with a view to protecting our planet.

Within international rules, every country must have the opportunity to build up and preserve key industries. All successful Asian development models have shown that real catching up is only possible with the help of the state and the regulation of international exchange. Opening up without the state and without protective rules for catching-up countries only means that the already powerful become even more powerful.

The textbook construct of mainstream economics of comparative advantage in international trade, with its conclusions regarding free trade and free movement of capital, must be exposed once and for all as the scientific fig leaf of international predatory capitalism. How sincere Western Europe really is about letting countries like Ukraine, Turkey, but also Poland and Hungary and other Eastern European EU countries up to Russia itself and the poor countries of the global South catch up, develop democracy and protect freedom, will be decided in this field.

Financial speculation as a litmus test

In this context, it is interesting to see how the EU is currently reacting to the price increases for raw materials. For what the leading elites in the influential EU countries themselves are prepared to accept in terms of real income losses and what they expect of their own poorer compatriots or – conversely – grant them in terms of support, can be taken as a rough indicator of what poorer countries can at best expect from the EU.

The majority of politicians complain in the media about the bagging of people on low incomes due to the rise in the price of heating fuel, fuel, electricity and food, and eagerly discuss price-curbing measures. Few responsible people clearly address whose pockets are being filled by this development, whether this is justified and, if not, whether this cannot be changed. And hardly anyone criticizes the fact that the price distortions caused by speculation undermine the powerful instrument of the market economy, which is to indicate real shortages through prices and thus to have them eliminated or at least alleviated in the long run.

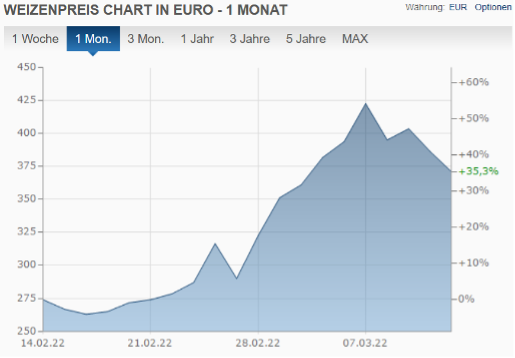

How can we tell whether price movements are based on real shortages or contain speculative components? Wheat, for example, will certainly become scarcer in real terms worldwide in the course of this year if the sowing and thus the harvest of the important wheat exporters Russia and Ukraine fall sharply due to the war, or if the supply of fertilizers from Russia to third countries shrinks. This argues for an increase in grain prices in the future. However, wheat has already become an enormous 35 percent more expensive in the four weeks since mid-February (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Source: Finanzen.net

The other strange thing is that the price trend reached a peak about a week ago. There, wheat was about 55 percent more expensive than in mid-February. After that, it went down rapidly. Did real wheat supply increase so noticeably in that one week to cause the observed price decline? Of course not – within one week, crop volumes anywhere in the world do not change so abruptly. Did the real demand for wheat decrease so much in this one week that the observed price decrease occurred? Of course not either – within one week, consumption volumes do not decrease so much and inventories do not fill up so rapidly that real orders would decline so significantly.

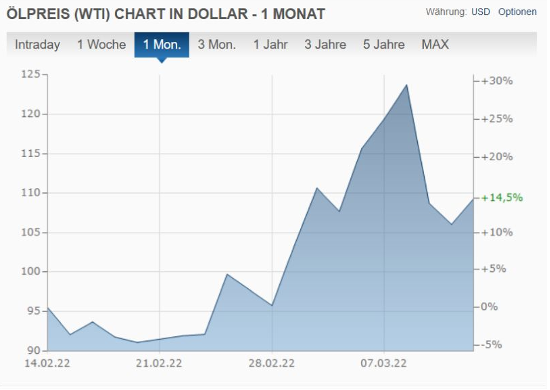

A similar picture emerges for the oil price (Figure 2): Significant price increase for four weeks by a good 14 percent with an interim peak of almost 30 percent.

Figure 2

Source: Finanzen.net

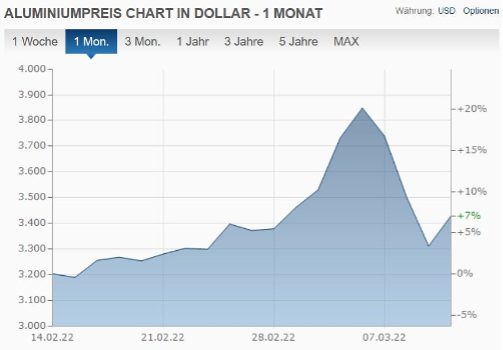

This pattern can be found in a wide variety of commodities, including aluminum (Figure 3): extremely steep short-term increases, followed by another steep decline, with an overall rising trend on average.

Figure 3

Source: Finanzen.net

The reason for these price fluctuations is that people speculate with commodities. Financial investors observe the political situation, add up 1 and 1 and buy papers denominated in wheat, for example. Other financial investors also jump on this bandwagon, and the price rally picks up speed. The actual magnitude of the price increase due to current and foreseeable physical scarcity, and which it should have as a meaningful signal to the suppliers and demanders of real quantities, does not matter much to the financial investors – the main thing is that they get in and out of the commodity markets in time to maximize their returns. And this harms all those who cannot and do not want to cover themselves with commodity paper but actually need real commodities, i.e. the input consumers and the end consumers, including and especially the low-income consumers. After all, they have to pay the peak prices or at least the margins with which the “real” traders of physical commodities try to hedge against the price turbulences.

Is it fair for those operating in the financial economy to enrich themselves at the expense of those operating in the real economy? And do “artificial” price turbulences strengthen the function of the market economy system to indicate physical shortages? Do they increase the population’s confidence in our economic system?

It is possible to ban speculation in commodities overnight. The states, which really have an interest in the situation of the population and in the international stability, can just prohibit purely financial speculation with raw materials. Those economic entities that do not produce or process commodities or use them as inputs in their production (and do not have warehouses in which to store commodities), as well as those that cannot be shown to have been established commodity traders for many years, can be prohibited from buying or selling securities backed by commodities. This would take a tremendous amount of momentum out of the markets from one hour to the next and would again allow commodity price movements to be used as an indicator of real scarcity.

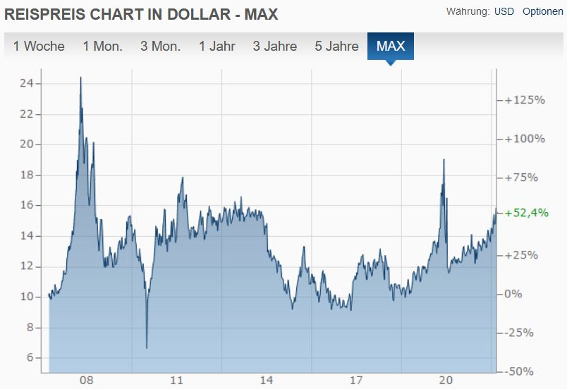

This is a litmus test of whether or not the elites are willing to give up their socially damaging sinecures. The fact that the speculation issue had to hit the population so massively in the Western industrialized countries before prices and state market interventions were even discussed at government level is an unparalleled indictment of the Western world. It exposes the phrases of the President of the EU Commission about Europe’s global leadership role through free and fair trade. After all, shouldn’t the speculation that has been going on for many years with the staple food rice (Figure 4), on which the survival of millions of people depends, have been reason enough to put a stop to the hustle and bustle on the financial markets?

Figure 4

Source: Finanzen.net

A new beginning is inevitable

Fundamental to a new beginning must be the realization that there can be no sensible trade between states without a sensible monetary system. Leaving currency issues to the market was the most important of the many economic policy mistakes made after the fall of the Iron Curtain. Russia was the largest and the most important country whose completely naive political leadership was thrown into the icy waters of the international capital markets in the 1990s. Without the Russian currency crisis and the failure of the Yeltsin government, Putin would not have come to power so easily.

The currency relations of all countries must be managed in such a way that no country can gain absolute advantages over another, which means that, in principle, real exchange rates must be constant. This means the end of the competition of nations repeatedly invoked by the EU Commission and by Germany. The Lisbon Treaty of 2007, which focused on the competitiveness of the EU as a whole and on the competitiveness of the member states, was a fatal mistake. It pointed in the wrong direction at the very moment when it would not have been too late for insight into the complexities of international cooperation.

The principle of a constant real exchange rate must apply outside and inside the European Monetary Union. Every country that joins or is associated must be given the guarantee that the exchange rate of its currency will be protected from speculation with the help of the ECB and valued in such a way that inflation differentials against EMU are balanced. Only for countries with extremely low levels of prosperity is entry into a global currency system at a slightly undervalued rate acceptable.

A first step of political emancipation and a strong sign of intellectual separation from the prevailing market doctrine would be the withdrawal of the Europeans from the International Monetary Fund. This would show the transition countries and at the same time the developing countries that they are really serious about a new beginning.

A new political beginning throughout Europe must also clarify its own attitude toward China. The American claim to hegemony, with its tendency to stylize China as the great adversary simply because it is capable of becoming bigger than the United States, must not be followed by Europe. China is big, it will become even bigger economically, and even if the country continues to be ruled dictatorially by a communist party for many years to come, ways must be found to deal with each other cooperatively in the long term. This includes not ignoring respect for human rights for the sake of trade. But it also means accepting the consequences of the Western system, which are becoming visible not least in the refugee camps on Lesbos.