Preliminary remark on the importance of macroeconomic analysis

There has been a lot of feedback on the first part of this series. Among them was the recurring question why the word “corruption” does not even appear in such an analysis, when we “know” that these countries cannot get off the ground because they are thoroughly “corrupted”. Even beyond corruption, many people believe that countries still in transformation from planned economy to market economy simply do not have the institutional prerequisites to develop dynamically. Therefore, a purely macroeconomic analysis is simply not meaningful.

This is a fundamental misunderstanding concerning the relative importance of macroeconomic analysis in relation to institutional or, as it is called in Germany, regulatory analysis or Ordnungspolitik. Countries with weak institutional conditions can also be economically successful if they manage to set the other parameters, namely the macroeconomic parameters, in such a way that the weak institutional conditions are overridden.

To put it mechanically and simply: If a country with a potentially weak growth and productivity performance manages to offer favourable monetary conditions to domestic investors (i.e. favourable interest rates and favourable real exchange rates), it can still stimulate investment and create enough jobs. On the other hand, a country (Brazil is the classic example) that has great growth potential but cannot get inflation under control and therefore has permanently exorbitantly high interest rates and whose currency keeps appreciating in real terms cannot use its potential.

Corruption in thousands of different forms exists in all countries of the world (including Germany, by the way) – albeit to varying degrees. No one can even begin to quantify the significance that “corruption” has on economic development. But although there has always been corruption in some form or another, a great many countries have been absolutely successful in the past when faced with favourable macroeconomic conditions. An Italian colleague once put it this way: in my country, there is evidence that corruption has existed for 2,000 years, but it is only in the last twenty years that economic development has been much worse than in comparable European countries. This is obviously not due to corruption, because it has not changed.

One can also put it the other way round: If already the Western countries with their (by definition!) perfect institutional conditions need an extremely low interest rate level or a real devaluation to develop dynamically, then a developing country or a transition country must under no circumstances have worse macroeconomic conditions to be successful. If it has much worse macroeconomic conditions, this is exactly where economic policy must start, because the country with its poor institutional conditions can never be successful with worse macroeconomic conditions than those prevailing in the Western countries.

The reasons for the economic decline

That is precisely the point here. We do not claim to be experts on the institutional or political conditions in Ukraine or Russia. But if we compare the macroeconomic conditions for successful development in these countries with the macroeconomic conditions in Western countries and find that they were and are much worse in Eastern European countries and Russia than in the West, then we can stop thinking about corruption or other institutional deficits. Then one must first ensure that the macroeconomic conditions for successful development are in place. This in no way excludes addressing the institutional issues and problems and bringing them closer to a solution. However, the latter is an effort that will never lead to success as long as the overall macroeconomic constellation is not development-friendly.

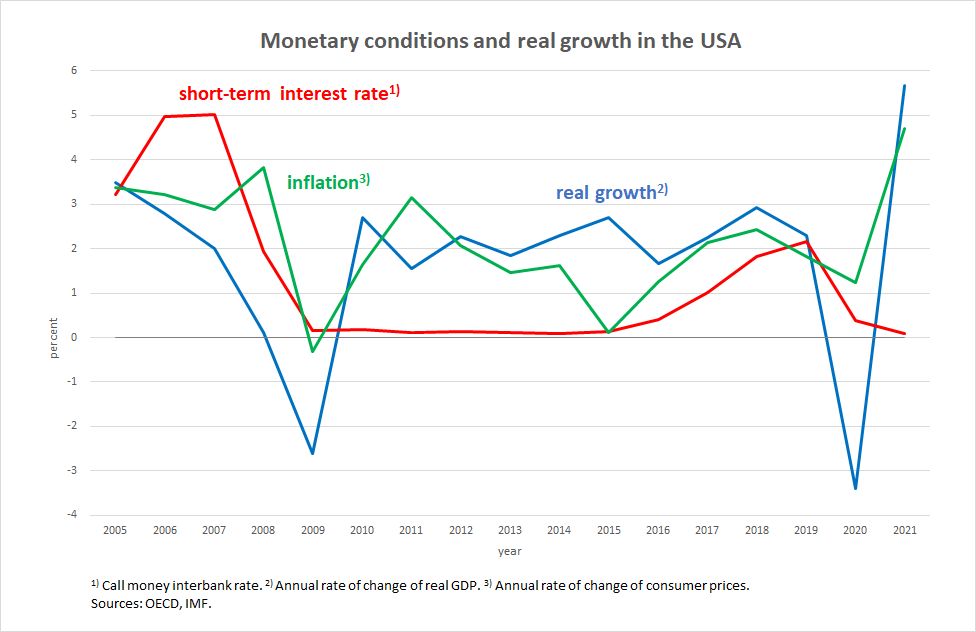

In the following, we first present the interest rate level, the inflation rate and real growth for the USA, the EMU, Russia, Ukraine and for China. Figure 1 shows that in the USA the short-term interest rate rose significantly shortly before the deep recession of 2008/2009, but remained very close to zero for several years after 2009. Real growth (real GDP) was very stable from 2010 to 2019 and inflation was also low and fluctuated little.

Figure 1

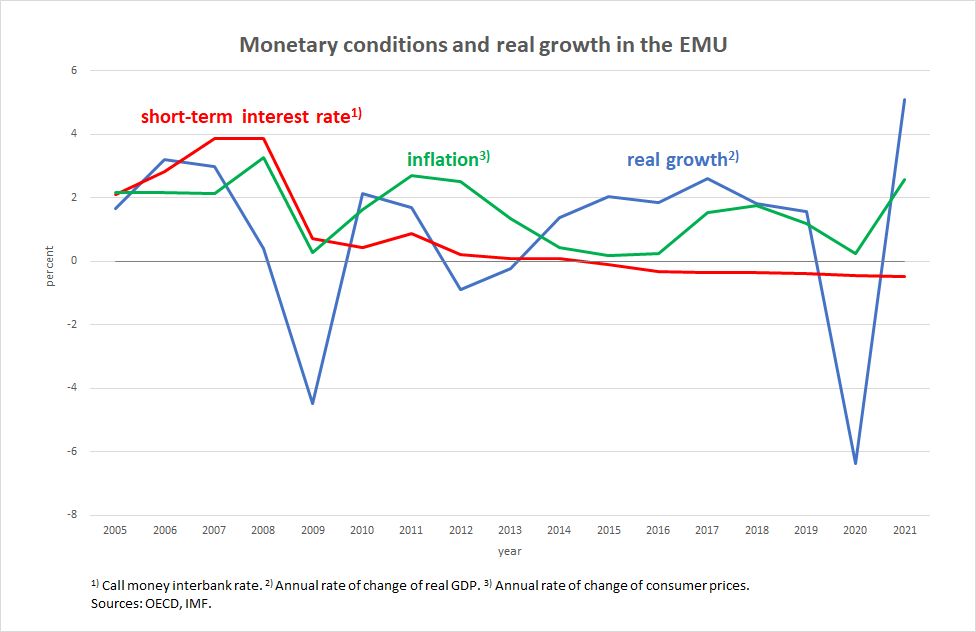

In Europe, more precisely in the EMU, the same ten years were somewhat less stable because monetary policy was less consistent after 2009 and there was the euro crisis (which was mainly related to real exchange rates): after the deep recession due to the 2008/2009 financial crisis, the euro crisis led to another recession in many European countries because of wrong economic policies in the form of fiscal restraint (Figure 2). Even after that, Europe was much less willing than the US to use expansionary fiscal policy to support the recovery and significantly reduce unemployment.

Figure 2

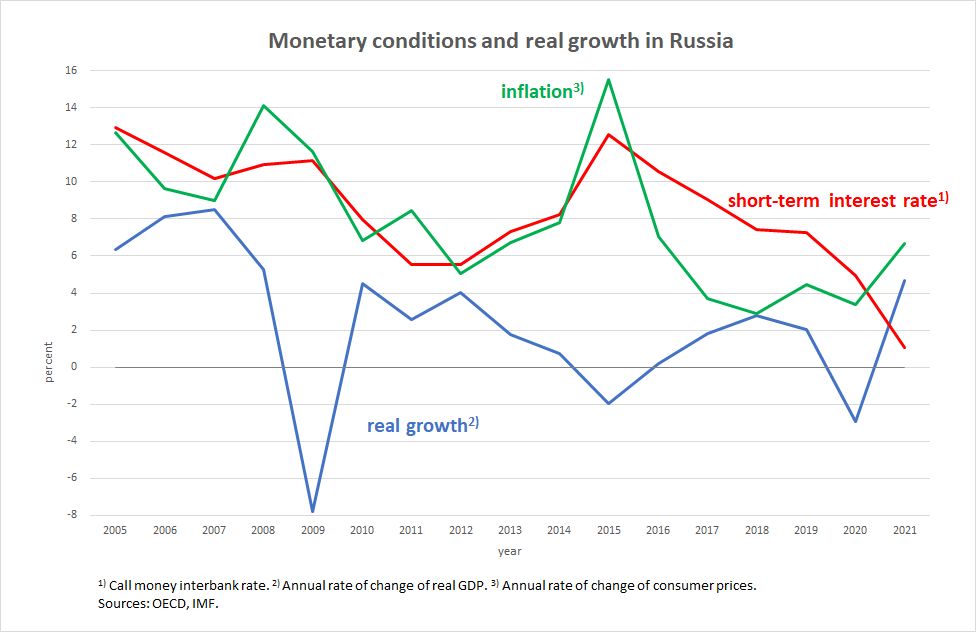

The fifteen years in question were completely different in Russia (Figure 3 – with a changed scale!). Real performance was consistently weak after the financial crisis of 2008/2009, which hit Russia extremely hard, with GDP falling by almost 8 per cent in 2009. Inflation was high and very volatile. Interest rates largely followed the inflation rate, which might give the impression that real interest rates were not very high at all. But with a volatile inflation rate, it is not easy or even impossible for potential investors to predict what the inflation rate will be in ten years. Thus, even an interest rate that in retrospect may be low in real terms, i.e. after deducting inflation, may have been much too high for the investor in advance. This is because an investor cannot firmly expect that the inflation rate and thus his own price increase possibilities will remain as high over the term of the loan as they were when the loan agreement was concluded.

Figure 3

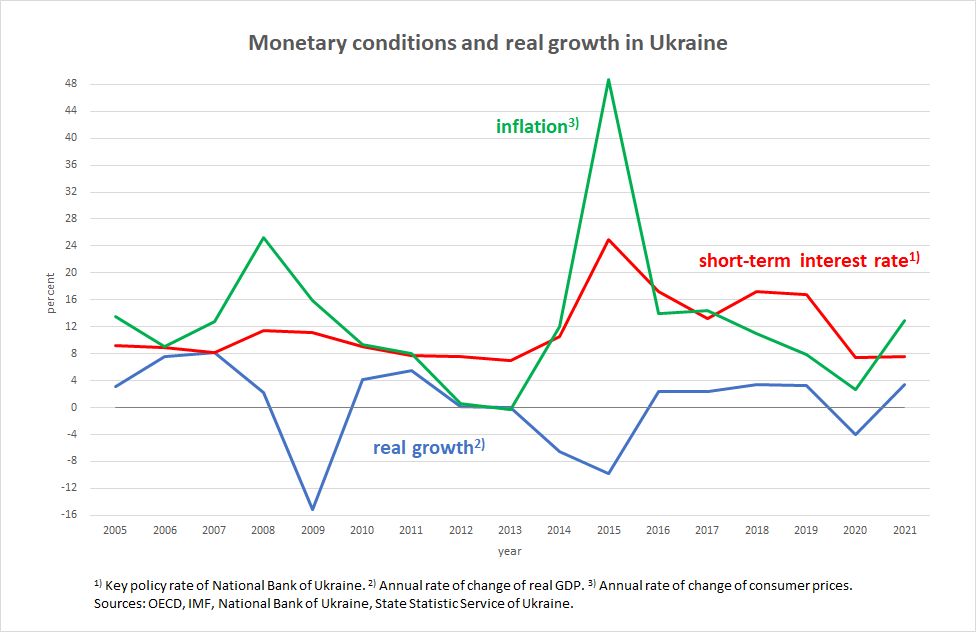

The situation is even worse in Ukraine (Figure 4, again modified scale!). Here, real development is even weaker than in Russia, and monetary conditions are simply prohibitive for growth and development. Even before the 2008/2009 crisis, when Ukraine’s GDP fell by over 15 per cent, inflation reached over 20 per cent. During the turmoil of 2014/2015, GDP fell again by almost ten per cent and inflation rises to almost 50 per cent, resulting in record interest rates that remained very high until 2019.

In addition, as we will discuss in more detail in the next part, currency relations fluctuated very strongly and there were repeated unjustified revaluations of the hryvnia. With such a constellation of important macroeconomic data, it is no use transferring a few billions to this country or simply entrusting the country to the IMF. The IMF has practically nowhere in the world succeeded in avoiding such constellations and finding stable working solutions because it simply relies on the wrong concepts.

Figure 4

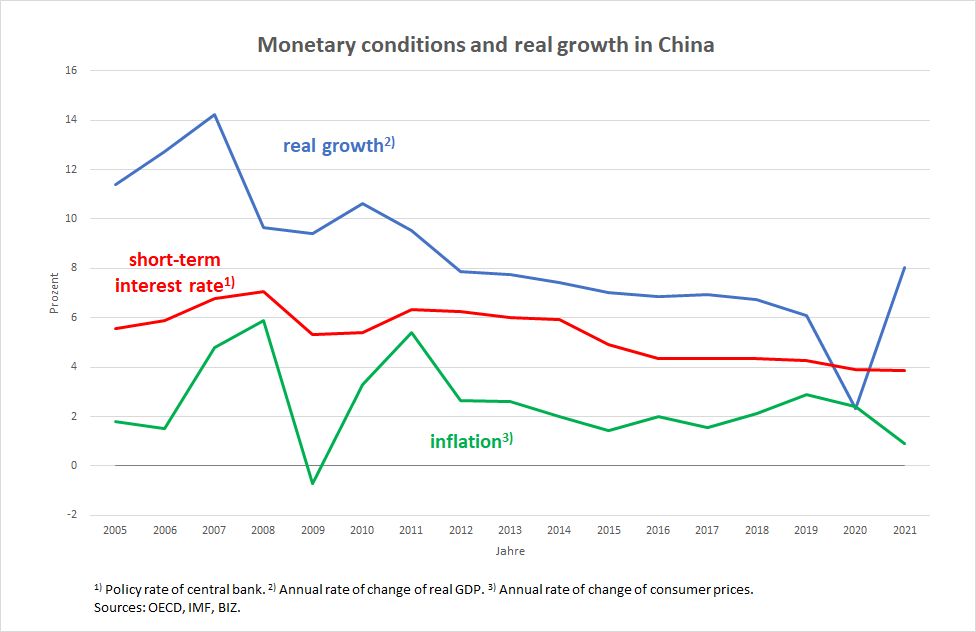

To illustrate what a good macroeconomic constellation looks like – obviously without the IMF ever being involved – we have compiled the same data for China (Figure 5). Here, inflation and interest rates are impressively stable and low, creating excellent conditions for investment. China was also well protected externally via a very stable exchange rate that was certainly significantly undervalued at the beginning of the opening in 1993. China is one of the few countries in the world that has not slavishly followed Western recommendations à la Washington Consensus in terms of macroeconomic management, and it has done extremely well with it.

Figure 5

If one takes into account how often German companies complain about corrupt structures in China and how poorly this country scores on Transparency International’s Corruption Index (CPI) – of which one may think more or less highly – it becomes clear what we explained at the beginning: Investment-friendly macroeconomic constellations in the monetary sphere spur economic development, even if institutional structures leave much to be desired. And vice versa: even with better conditions in terms of corruption – Georgia, for example, to name just one example, has clearly been performing better than China for years – longer-term prosperous development is practically impossible without good monetary conditions.

Read in the third part why a functioning monetary system is indispensable.