A new issue, that is in fact age-old, is receiving enormous interest these days from economists, social scientists and journalists. The danger of automation, or the process by which machines render labour to be obsolete, is seen as a real and fundamental danger. Nothing about this is new. The English economist David Ricardo wrote about it in On Machinery two hundred years ago. The same misunderstandings and confusions always return.

Philip Plickert recently wrote an article about automation in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ) (see here). This article thoroughly shows how prominent the on-going discussion has become. Plickert refers to several Anglo-Saxon ‘experts’ who research the possibilities and the consequences of increasing automation. However, these experts do not seem to recognise that they are reproducing ancient prejudices. The author himself seems to be fully aware of it but nonetheless fails to realise the implications of it because he is blocked by other prejudices. The FAZ quotes labour researcher Richard Freeman of Harvard University. Freeman says that: ‘As soon as robots and computers can do something cheaper, they take people’s jobs away – except when workers are willing to accept lower wages.’

Freeman’s statement epitomizes a kernel of the confusion that surrounds the concept of automation. Of course, machines can destroy certain jobs (but not jobs in general) because they can provide an enhanced performance, reliability and speed. Nothing has changed in this regard since the dawn of human history. However, Freeman is wrong: if people, at the start of the process of mechanic rationalization (which began well before the industrial revolution) would have been successful at preventing their job losses, it would be difficult to explain how technological innovation led to rising prosperity. In fact, this phenomenon would have simply never occurred.

The author of the FAZ correctly notes that: ‘In the long run, the expectation that the new industrial world would no longer provide employment turned out to be false. The contrary is true: rising productivity lead to increased prosperity for the population as a whole. The use of modern machines made production much cheaper, prices fell, and with falling prices demand and consumption increased. Instead of old occupations in agriculture and handicrafts, which became obsolete, many new industrial jobs were created instead.’ This is an ambitious statement and we should be suspicious when the FAZ discusses the relationship between rising productivity and rising prosperity. Why do prices have to drop for prosperity to rise?

But, first things first. We explained the proper relationship many times already. In our book The End of Mass Unemployment, Friederike Spiecker and I put it this way:

“Is it not obvious? Unemployment is an inevitable fate. What was produced yesterday by many workers at an assembly line, becomes automated today. Robots do the work. Yesterday, workers packed and labelled the finished goods. Today robots pack, label and send goods to their destination. The whole process, from beginning to end, is controlled and done by computers. As a result, more and more people lose their jobs. Some find no new employment, not even after repeated re-training hence creating long-term unemployment. Are we in the process of becoming unemployed because of the introduction of increasingly smart and powerful machines? Anyone who ever took a look at a car manufacturer’s assembly line will see a dystopia of robots that make human labour obsolete. There are almost no workers left. Machines do everything. It makes a lasting impression. It is hard to not feel sympathetic for labourers who stormed factories a century ago to destroy machines that took their work away and put their means of survival in jeopardy.’

But sometimes impressions are deceiving. We all live on planet earth, which is merely a very small sphere, made of mostly iron, that rotates around the sun according to the laws of gravity. It took mankind a long time to understand this. Until four hundred years ago, almost nobody understood it: the rising and the setting sun seems to tell us something very different than gravitation. It is the same for economics. The mechanism that creates wealth from capital (i.e. labour power and machinery) seems to destroy employment, just as it seems that the sun rotates around the earth. At first glance, automation seems to be a mysterious and destructive force, until it is properly understood.

Let’s simplify things to the extreme for a moment. Imagine Robinson Crusoe on his desert island. He keeps himself alive by catching fish. In order to not have to spend all his time fishing, he makes himself a fishing rod. This investment pays off: he will now spend less time catching fish; therefore, his productivity can increase. For example, he can now build himself a hut without starving. The aim is, of course, to improve his living conditions and his well-being. Crusoe can choose what to do with the time he saves: he can use it for the production of other goods or for leisure. But he cannot consider being idle (or, if it was a social system, being unemployed) whenever he is not working. Ultimately, the rod increased his productivity and led to his ability to acquire new goods (e.g. the hut or added leisure).”

In the next two parts of this written series, we will show how the same relationships exist in highly complex modern societies. We will present empirical evidence that shows that ingenuity and technological innovation do not lead to increasing unemployment. This premise, in fact, can be shown perfectly well.

Increases in productivity can lead to growth in an economy‘s real income. If productivity gains lead to a general rise in real income, everybody would be able to afford more goods and enjoy more leisure time. If the demand for goods increases then it is necessary for companies to have appropriate supplies and for customers to receive real income growth in order to consume the extra production output.

Increases in leisure time are a little more complicated because it is not easy to determine whether the vast majority of workers favour less total working hours. If workers agree to less working hours, it should be ensured that the option of shortening working hours benefits all workers equally. One must, at the same time, prevent the collapse of demand and see to it that companies create new vacancies.

Now we still need to answer the question of how to generate rising incomes and rising demand. Increasing demand is absolutely necessary in order to avoid layoffs and downscaling. According to the FAZ, the only way to accomplish this is by reducing prices. This is indeed a possibility in the presence of rising productivity. If there is sufficient competitive pressure, companies will decrease employment in order to reduce prices, or, they may let their output prices rise at a slower pace than that of their competitors. Consequently, the general price level decreases, nominal wages remain constant and real wages rise. Rising real wages generally (if there is an unchanged propensity to save) lead to increasing demand for goods and services, which – in itself – leads to positive job effects and thus compensates the negative effect of layoffs.

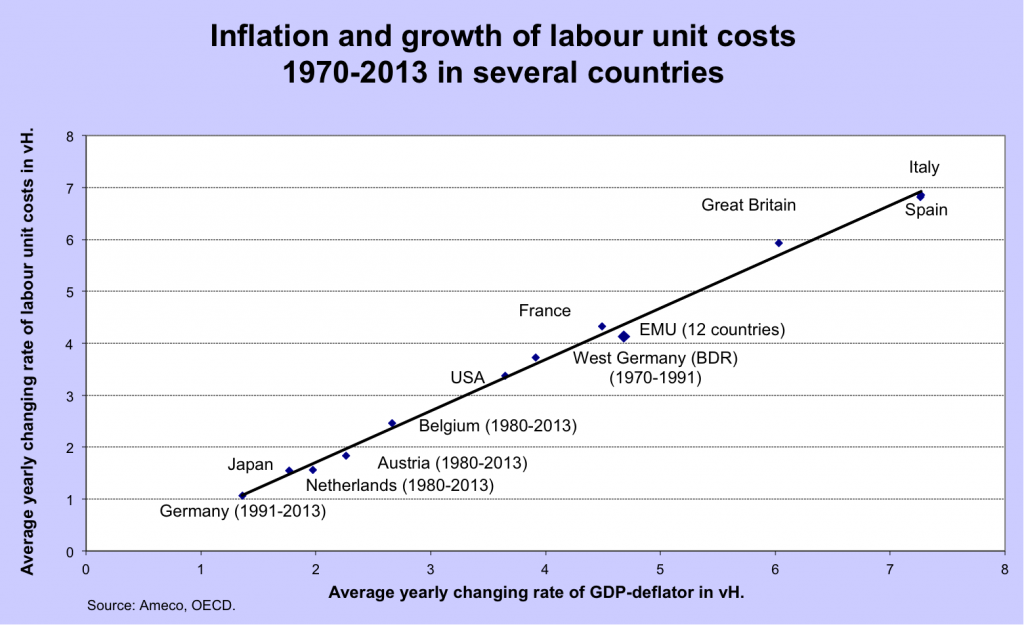

But why is it necessary – as is assumed in the FAZ article – for prices (or the price level) to fall in order to generate an increase in real wages and demand, which in turn, would make it possible to increase the volume of production with an unchanged number of employees? The answer is simple: it does not need to fall. Changes in price levels that usually correspond to positive inflation targets are wholly dependent on the evolution of nominal wages. We have shown the relevant empirical relationship already many times (see Figure 1): Real wages will rise year-after-year in accordance with increases in productivity if nominal wages follow productivity increases, plus the respective inflation rate or the inflation target (measured by GDP deflator). If nominal wages were to grow at such rates then companies would be able to contribute to a slightly positive inflation rate. This is not a problem. In Germany, from about 1970 to 1991 (until the German unification) inflation was about 3.5% per year. Since the mid-nineties, wage moderation policies greatly reduced nominal wage increases. These pressures caused only about 1% of inflation to result from the interplay of nominal wages and productivity growth.

Figure 1.

Over longer periods, such as the ones we consider here, competitive pressures in product markets usually lead to a decreasing inflation rate if wages do not rise in accordance with what is called the ‘golden wage rule,’ (i.e. the rise of productivity plus an agreed upon inflation target (set at 2% by the ECB)). And this is a problem. Persistent downward pressures on nominal wages lead to enduring low inflation rates or even deflation (as in Japan since the early nineties). Furthermore, they create a lag in real wage growth relative to productivity growth. From this, it follows that it is perfectly rational to forego using pressures on nominal wages in attempting redistribution. Instead, nominal wages need to increase from the outset in tandem with productivity growth and the inflation target.

This is a message that a newspaper such as the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung is unlikely to accept. The economists of the FAZ solely consider the necessity of flexible wages, which implicitly supports real wages lagging behind productivity growth. However, this is counterproductive. If real wages lag productivity, as has been the case for the last fifteen years in Germany, part of the potential productivity output will never be realised because there is insufficient demand within the internal (national) market. As a consequence, unemployment will inevitably rise.

Everybody saw what happened. Germany let the evolution of its wages lag in relation to the evolution of its productivity. It told its trading partners that they are living beyond their means. German wage moderation led to a situation in which other Eurozone countries were no longer competitive. As a result, the German trade surplus grew year after year, while trade deficits were accumulating in the partner countries. Germany’s policy was ‘successful’ because its partners had no means to defend themselves. It is no longer possible to depreciate their currencies. In the longer term, this situation is unsustainable. The deficit countries cannot cope with their ever-increasing debt levels. German wage moderation has become a danger to the existence of the euro zone.

For the world and certainly for relatively closed economies such as the US or Europe, the result is entirely clear: declining real wages and real wages that lag behind productivity growth increase unemployment. When automatisation and robotisation (and the increases in productivity that go along with them) are not used to create additional demand, companies will have no other choice but to cut back on their workforce. This much is perfectly clear. There is, however, no logical reason for raising real wages by relying upon imperfect market processes that create major negative side effects (i.e. unemployment). We can do much better. It is entirely possible that the social partners, or the government itself if necessary, make sure that nominal wage growth corresponds to increases in labour productivity plus the inflation target. Anyone who supports the setting of an inflation target by the Central Bank must, on logical grounds, agree to steer the evolution of nominal wages in accordance with this target. Those who disagree either do not understand the macroeconomic necessity of this mechanism or they are ideologues pursuing a specific and counterproductive agenda.

In the second part I will explain how and why labour productivity concretely evolves.