Sometimes a very simple statement can tell you abruptly how a society lies to itself in order to avoid unpleasant contexts. So it is with inflation – and so it is with unemployment. One year of high price increases, usually called “inflation”, has made society and politics quake; forty years of unemployment, on the other hand, are simply pushed aside because they do not fit into one’s own world view.

In a remarkable interview, ECB Executive Board member Isabel Schnabel offered a deep insight into her economic worldview. The result is shocking. Ms Schnabel not only defends the completely failed doctrine of the so-called monetarism, but her historical view of unemployment is characterized by great ignorance. Both are fatal, because the false lessons one draws from history often directly explain the mistakes one makes in the present.

It is more than astonishing how Ms Schnabel sees the situation on the labour market in the 1970s compared to today. She said:

“Above all, we have an unusually strong labour market. Unemployment is – and this is a huge difference from the 1970s – at an all-time low in the euro area. We have great labour shortages. But at the same time, of course, that means that in this bargaining process workers have more bargaining power…”

This is more than problematic for their judgement of the workers’ response to the current temporary price increases. If this (completely wrong) view prevails throughout the ECB’s Executive Board, it explains the ECB’s misjudgement of the duration and danger of the temporary price increases. Now the ECB has even raised interest rates again, although the danger of the emergence of real inflation has meanwhile been largely averted (as shown on this page recently).

But the ECB is by no means alone in this misjudgement. Time and again one hears, especially in Germany, that there is currently a particularly large shortage of skilled workers and that even jobs that require only low qualifications are hard to fill. This may be true in the eyes of companies that were used to always being “supplied” very quickly with the qualifications they needed by the government employment office. In the eyes of an entrepreneur who lived through the 1970s, the statement that there is a labour shortage today is a bad joke.

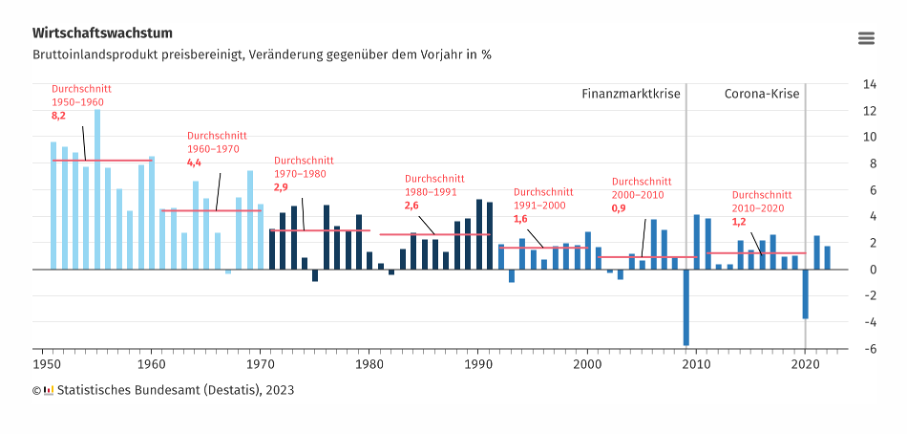

Before the first oil price explosion in 1973, Germany and half the world had been through 20 years of a super boom, which, as the Federal Statistical Office has just shown in historical statistics for Germany (Figure), picked up speed again at the beginning of the 1970s. The situation on the labour market was very clear. In Germany there were about 100,000 unemployed and about one million vacancies, a ratio of one to ten. There was practically no labour to be found because the majority of the 100 000 people who were registered as unemployed at all were registered with the employment office only just before taking up a new job.

Real GDP growth in Germany

Today there are about 2.5 million officially counted unemployed and about 800 000 (also officially counted) vacancies. That is a ratio of three to one. Anyone who compares a ratio of one to ten with a ratio of three to one and comes to the conclusion that in the second case there is a “historical” labour shortage and that workers therefore have more bargaining power today is fundamentally wrong.

On the basis of this misdiagnosis, the ECB evidently ends up stoking fears of a wage-price spiral, which are completely unfounded. Not only because of the inverse ratio of vacancies to unemployed, but also because of many deliberate political actions during the decades of neoliberalism, the trade union movement in Germany and throughout Europe has been massively weakened. Not least under the Red-Greens at the beginning of this century, with the Hartz IV legislation, the trade union movement and the ability of trade unions to mobilise their members for strikes was dealt a severe blow in the largest country in the monetary union. Did all this pass Isabel Schnabel by? If so, she has no business in the place where she sits.

The fairy tale of the labour shortage

One wonders, however, how the economy was able to grow strongly at all at the beginning of the 1970s when, compared to today, there was no possibility of recruiting labour from outside. The answer is simple: the companies had to turn all available workers into skilled workers in their own companies with the help of intensive training. Those who could not find employees had to resign themselves to the possibility of expanding the business with the existing workforce. And there was every reason to invest in fixed assets, more in productivity-enhancing ones than capacity-expanding ones.

The employers’ complaints about a lack of skilled workers, which are launched into the public every few months, are an expression of a free-supply mentality on the part of employers that cannot be justified by anything and that was able to emerge in the past decades because unemployment was consistently high. Those who invoke self-healing through market forces in their Sunday speeches immediately become supporters of state interventionism when it comes to labour availability. However, the state has no obligation whatsoever to ensure a smooth supply of labour. The employers’ mentality is particularly blatant when they also believe that this supply must always come at the same wage conditions.

If you urgently need labour, you have to do what you always do when you cannot easily acquire a scarce good: you have to spend more money. This is the only way to tap potentials on the labour market that are not otherwise available. But when it comes to higher wages, employers always like to forget that they are in a market economy and not in a state provision institution.

But the politicians have themselves to blame. When federal ministers travel halfway around the world to recruit workers in a developing country, they give the impression that this is a genuinely political issue. Solving the shortage of skilled workers through immigration is, however, unparalleled cynicism in a society that does everything in its power to close its own borders as perfectly as possible to immigration from poverty, even in disregard of human rights.

It goes without saying that we are allowed, for “our economic reasons”, to poach from developing countries the skilled workers they also urgently need. At the same time, however, we do everything we can to prevent immigration for economic reasons (the economic reasons of the migrants, that is). More schizophrenia is hardly possible. Migrants can also be educated, but of course it costs more than poaching educated workers already in their countries at the expense of their taxpayers.

The solution to the problem is simple: there are as many workers in a country as there are. Where does one get the chutzpah to say that we must grow more than we are actually able to and that the gap must be filled by the immigration of well-educated skilled workers? If society is able to increase its prosperity through rising productivity, all well and good. If it fails to do so, it must adapt to what it has. It must be an absolute taboo, especially for “value-based” nations, to tamper with the labour potential of other countries.

What we are really interested in is maintaining our salary hierarchies. Where would we be if a salaried roofer earned a quarter of what the personnel manager of a car company takes home? Or a train conductor half the income of a savings bank director? Or a nurse three-quarters of a teacher’s salary? That would be truly unbearable. We really don’t want to take the market economy that far. Skilled workers simply have to be available in abundance and cheaply so that the top fifth in the income hierarchy can continue to live in luxury not only in absolute but also in relative terms.