The British Economist is considered the serious business newspaper par excellence. Anyone who wants to read fundamental, albeit conservative, ideas on economics and economic policy cannot avoid dealing with the Economist. The publisher even has an “Intelligence Unit” that offers data and analyses that are supposed to meet scientific standards. On 3 May, the Economist devoted its cover story to the American national debt and came to the conclusion that there is no sustainability.

The story in the Economist, as in hundreds of other newspapers around the world, starts with the imminent threat of an absolute debt ceiling in the USA, which currently stands at 31.4 trillion US dollars or 117% of GDP. If there is no quick agreement between the administration and parliament, the US government would be forced to cut government spending, raise taxes or, the most unlikely case, suspend servicing of US government bonds, i.e. allow what is called a sovereign default.

The American debt ceiling is a truly ridiculous bureaucratic monster that has no economic justification whatsoever but attracts a lot of media attention every few years – right up until the point when the parties involved in the US agree to raise it after all, because anything else would simply be too stupid. But the Economist wouldn’t be the Economist if it didn’t dig deeper and ask whether, quite independently of the debt ceiling, the American national debt isn’t getting out of hand.

This is where it gets interesting, because it shows that even a paper that claims to provide serious analysis cannot jump over its narrow-minded neoclassical shadow. The Economist writes:

“Rates may come down in future. They may also stay high for a while yet. And in the higher-rate world that America now inhabits, large deficits can lead to pathologies. To fund so much borrowing, the government must attract a greater share of savings from the private sector. This leaves less capital for corporate spending, reducing the ability of firms to invest. With less new capital at their disposal, workers become less productive and growth slower. At the same time, the government’s need to attract savings from investors at home and abroad can place upward pressure on interest rates. The risk that investors, especially foreigners, decide to shift money elsewhere would add to America’s fiscal vulnerability. That, in turn, would constrain the state’s ability to deploy stimulus in the face of cyclical slowdowns.”

Here we go again: the state must not overuse the savings of private households, because otherwise there will be too little left for the real investors, the companies. The argument goes that the American state also withdraws savings from abroad, which could even lead to rising interest rates. Those who do not want to invest in the USA will simply go elsewhere. This is classic “crowding-out”, according to which the unproductive state crowds out the productive private investors and asset holders decide how much debt a state may take on. Neoliberals have used this argument for decades against the expansion of state activity – and they have been successful.

Twenty years after a real turning point on this issue, one can still come up with the old argument without the entire academic community, including conservative circles, tearing one to shreds in terms of argument. The turning point can be dated to the beginning of the century. Since then, the savings behaviour of the entire private sector and especially that of companies has changed so fundamentally in the USA and in almost all major industrialised countries of the world. In the new settings, crowding-out sounds like a fairy tale from long ago.

We just love fairy tales…

One of the most beloved stories in economics is the one about a state that is so smart and wise that it only intervenes in economic activity when there is no other solution at all. Neoclassical economists and Keynesians can agree at any time of the day or night and within minutes that the state must act countercyclically “in crisis” or “in recession”, i.e. take on debt to stabilise the economy. Neoclassical economists, however, insist that the state must then save during the upswing and reduce its debts again with the help of surpluses. If it did not do so, it would end up with constantly rising debt levels, which in the long run would entail unsustainable interest burdens.

This is a nice story and for many decades the only thing people argued about was whether the states would really do this with the surpluses in the upswing. The Keynesians were full of confidence in the rationality of the state here, but the neoliberals were highly suspicious because they generally did not trust the state to behave rationally in their sense.

However, as is so often the case with simple, beautiful stories, they unfortunately do not quite capture reality in all its cruel complexity. People have settled comfortably into this simple world, but unfortunately the world has just changed fundamentally and demands solutions that require from the one and the other alike what they find most difficult: rethinking!

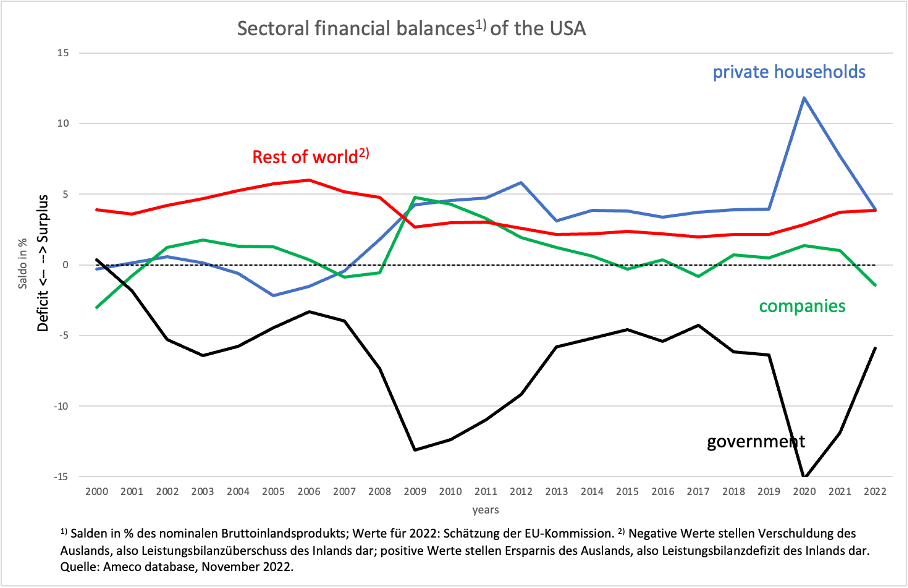

Let’s take a look at the US (figure), which is typical of a large relatively closed economy, i.e. an economy in which external relations are not of significant importance. The financial balances of the sectors (net saving is above zero and net debt is below zero) here very clearly show the fundamental change that emerged at the latest with the global financial crisis of 2008/2009, but which was also indicated beforehand.

Figure

Corporations, which until the turn of the century were still predominantly on the debtor side, have now become predominantly comfortable on the saver side alongside private households. Since the US has a current account deficit (i.e. it is also burdened by net foreign savings), there is in principle no other place for the state than on the debtor side.

…and do not want to take note of the facts

The reason for that is simple: these curves have the stupid habit that they must always add up to zero. No one can incur debt, i.e. live beyond their means, unless someone else lives below their means, i.e. spends less than they earn. If everyone tries to save, the economy collapses, and the state has to step in with new debts and new demand to prevent the worst.

Which means nothing other than that the market economy that both the neoliberals and the traditional Keynesians dream of has not existed for more than two decades. In the USA and Europe, foreign trade does not play a major role (for the world as a whole, there is no foreign trade at all), so they cannot, like Germany, rely on foreign countries, in the form of current account deficits, to take on the role of debtors.

If companies systematically switch sides almost all over the world, the fate of state finances is sealed. The state will then have to incur new debt forever and ever, no matter what the absolute debt level is. Crowding-out does not exist at all because the state and the companies are not on the same side of the financial balance. Small mercantilists like Germany may escape this compelling logic for a while yet by running even higher current account surpluses, but they are the famous dwarfs whose shadow is only so long because the intellectual sun stands close to the horizon in their country.

In this new world, contrary to what the Economist believes, investors no longer have to worry about where to put their money if a country’s public debt seems too high to them. After all, there is no alternative to states that are heavily indebted. If companies everywhere save, government debt everywhere will rise permanently and the few mercantilists will come under more and more pressure from those who are exploited by them.

In this new world, there is no need to philosophise about whether and how quickly the state should take advantage of “the good times” to keep its debt in check. The good times simply no longer exist because corporations are so strong and so powerful that no one dares to push them back into the role of debtor through higher taxes. The strength of the corporations is the direct result of the neoliberal revolution in the second half of the last century. This means nothing other than that it is the neoliberals, with their course of coddling the corporations, who are directly responsible for the fact that the national debt is increasing immeasurably. Congratulations!

The free-market capitalist system is on a direct path to collapse worldwide if the states do not incur debt. If one combines the power of companies to choose their side of the savings coin with the demand on the state to reduce its debt, one chooses – given the ever-present propensity of private households to save – a constellation that is impossible for logical reasons. If ignorant politicians do not inform the citizens in time about the objectively given necessity of state debt, sooner or later swindlers will win elections who claim that they can make the impossible possible.