Just imagine that the European Monetary Union (EMU) had never existed, the European Central Bank (ECB) had never been founded, Germany was still directed by the Deutsche Bundesbank in monetary matters, and there were the same post-pandemic shortages and the same speculation-induced price increases for individual products as at present. What a disaster that would be!

After the global pandemic, the German Bundesbank would undoubtedly be under strong pressure from the many “experts” who tell the story day in and day out in Germany of the great inflation that is now imminent and that must be fought immediately with interest rate hikes.

Raise interest rates by hook or by crook?

Even worse: the greatest scaremonger on inflation, Hans-Werner Sinn, would probably have been a member of the Executive Board of the Deutsche Bundesbank and would have left the Bundesbank heirs after his retirement who would be in no way inferior to him. Which is to say that in an economic situation like the present one (cf. Figure 1) the inflation fighters in the Bundesbank would raise interest rates with all their might.

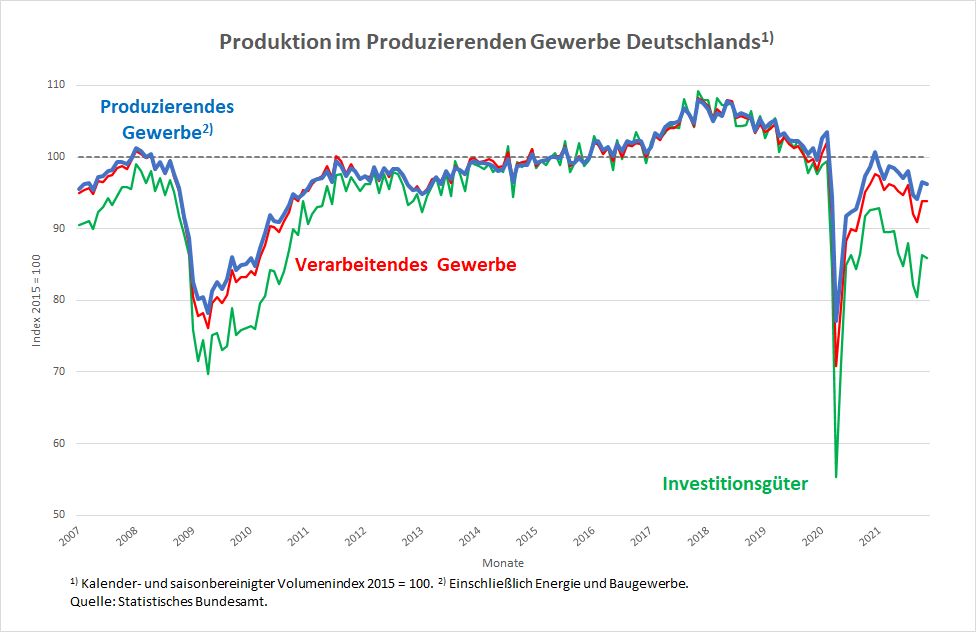

Figure 1

The German economy (the figure shows the manufacturing sector, i.e. industry plus construction, plus manufacturing and capital goods production) has recovered somewhat from the deep corona-induced slump. But it has not yet returned to its pre-crisis level. And, as Figure 1 shows, it is already on the brink again and in great danger of crashing again. The climate index of the ifo Institute clearly points in the direction of recession for the parts of the economy that are susceptible to economic cycles. In autumn last year, 3 ½ million people in Germany were still out of work (unemployed plus short-time work extrapolated to full-time, not to mention the other underemployed) and the number of short-time workers has recently risen again.

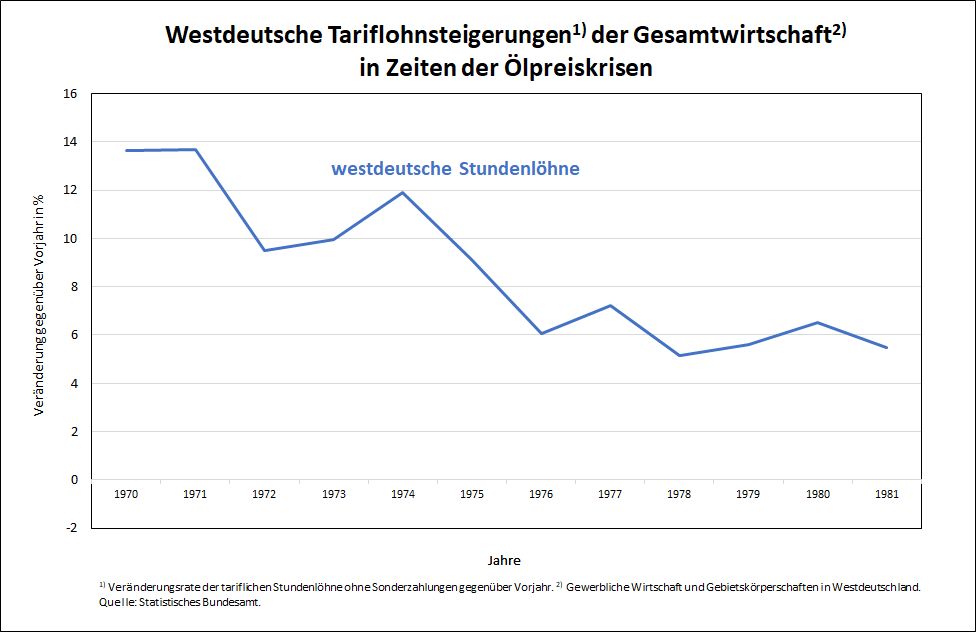

Everywhere parallels are drawn with the oil price crisis of the 1970s, where, according to the inflation fighters, it became clear that inflation coming in via imports had to be fought vigorously right away in order to prevent worse. The fact that in the 1970s wage developments in response to import price increases were in completely different spheres when the economy in West Germany and in the other industrialised countries was at full employment, is deliberately overlooked (Figure 2): At that time, the lowest value of the average nominal wage increase in West Germany was 5.1 per cent in 1978. At the beginning of the 1970s, there were about one million job vacancies and 100,000 unemployed in Germany and thus a completely different distribution of power between the bargaining parties. Today we have 800,000 vacancies and 3 ½ million unemployed.

Figure 2

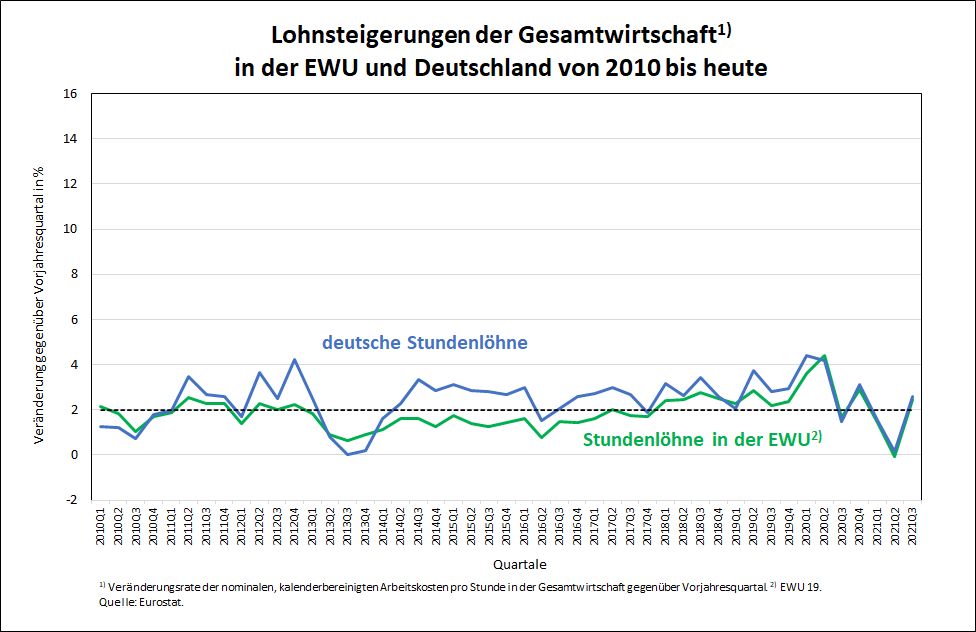

With an average wage increase of 2 ½ per cent in the last ten years and 2.6 per cent in the last two years, the bargaining partners have moved away in an almost unheard-of way from the growth rates that were commonplace in the 1970s. German and European wage settlements are even below the ECB’s inflation target of 2 per cent in terms of nominal wage growth on average over the last five quarters that are available (Figure 3).

Figure 3

The Bundesbank has indeed made such mistakes …

What we are describing here in the subjunctive is by no means fiction. The Bundesbank has made such serious mistakes several times in its history, without anyone in German politics or the public taking any notice of it until today. The first big mistake was already the sharp monetary tightening after the second oil price crisis in 1979, when wage developments had largely calmed down and the danger of inflation was simply imaginary.

In 1992, the Bundesbank raised interest rates in a situation where the German economy was already on a downward slide, causing a recession that hit the whole of Europe hard. One should also not forget the years 2008 and 2011, when the ECB, under significant German influence (the chief economist was a German, Jürgen Stark), raised interest rates at times when this was completely inappropriate.

… and that for the whole of Europe

What is even more awesome is that Hans-Werner Sinn and those like him are talking about the ECB and thus about Europe, where the “bazaar economy of Germany” (Hans-Werner Sinn’s completely off the mark description from the early 2000s), with a current account surplus of almost seven percent of GDP again in the meantime (6.9 percent according to the Bundesbank’s current calculations for 2021), deprives the other countries of the euro area of any possibility of finding a solution to their employment problems via exports, just as Germany has done. This massive violation of European rules (see the so-called score board of the macroeconomic imbalance procedure, where the current account is one of the indicators accepted by all countries) is treated as a taboo by both the scaremongers and the rest of the German public, including the entire political spectrum, and is simply kept quiet.

To keep quiet about this is a declaration of scientific and political bankruptcy, because the effects of German mercantilism are enormous. Unemployment is still very high in most EMU countries because Europe – unlike the USA – slept right through the ten years after the financial crisis. Instead of doing everything that would have been necessary to approach full employment, also on the part of the states’ indebtedness, attempts were made under German direction to consolidate the state finances by force, although this was impossible according to the situation of the balances of the other sectors (for an explanation, see this paper).

Needless to say, business investment, which Hans-Werner Sinn and his comrades-in-arms say is crucial for a prosperous economy, has never seen an upswing in the past ten years. Figure 1 shows that the production of capital goods in Germany in particular is clearly on course for recession – after the severe slump of 2020! The index for incoming orders from the domestic market for German capital goods manufacturers was 100 at the end of last year – and this with an index calculated on the basis of 2015=100. In other words, although there is about as much domestic investment as there was six years ago, there is absolutely no talk of an investment dynamic that would tolerate interest rate hikes.

In this situation, wanting to raise interest rates would not only be irresponsible, it would be dangerous. One wonders why the German business associations do not go to the barricades when German economists implicitly call for slowing down an investment dynamic (because that is exactly what happens when interest rates rise) that does not exist.

It’s good that today’s ECB exists

One has to be glad that there is an ECB that has emancipated itself from the nonsensical German paradigms and, by and large, has so far not allowed itself to be infected by the Germanic inflation phobia. The ECB top brass rightly insists that the inflation phenomenon is temporary and that there is no sign so far of a price-wage-price spiral emerging, which would be the only justifiable reason for the central bank to step on the interest rate brakes.

The ECB, unlike the facile German commentators, knows how weak the European economy is and how far it is from a situation in which the trade unions could really succeed in pushing through significantly higher wage increases. Those who, on the other hand, simply claim that the trade unions could very well push this through in the current situation precisely on the grounds of the current higher inflation rate, overlook the reversal in the distribution of power between the bargaining parties that has prevailed for years compared to the 1970s. He also overlooks the fact that the Corona crisis has also left deep scars on the labour force in the particularly negatively affected sectors, which undermines the willingness to fight for higher wages.

The warning of a looming price-wage-price spiral cannot be justified with the frequently and for years lamented German shortage of skilled workers, because the alleged shortage should have led to more reasonable wage agreements in the last ten years, at least in Germany, which was not the case. Instead, the situation on the European labour market as a whole has not allowed the trade unions in Europe to reach wage agreements in the past decade that would have made it possible to achieve the European inflation target. How should this have turned into its opposite in and at the end of the Corona crisis of all times?

Dangerous inflation harms the poorest

It is also great that on the subject of inflation, it is precisely those who hardly give a thought to the poorest in society who are the ones to suffer, but who have explicitly opposed the introduction of a minimum wage and who, of course, do not advocate its dynamisation in line with the current rate of inflation or demand that for basic income support. This is because a compression of income distribution achieved in this way is rejected in these circles, mostly on the grounds that it is anti-performance and thus detrimental to economic development and ultimately to the poor themselves.

Even to suggest that interest rate hikes would eliminate the scarcity of individual goods or stop speculation with energy, housing and food is more than negligent. Real scarcity can only be overcome by investment and that is slowed down by interest rate hikes. Even if money became more expensive for speculative purposes, it would be the wrong way to try to fight speculation in this way instead of through regulatory interventions that prevent this abuse of the market economy. To risk an even deeper slump in spending on physical investment now would be existentially threatening for many workers and especially the most vulnerable among them.

The kind of inflation that can actually be dangerous for a dynamically developing economy is precisely not a condition in which the prices of some products are ten or fifteen percent higher than a year earlier. Inflation dynamics is a process in which, after a triggering moment, prices and wages keep pushing each other upwards, without the price increases having anything to do with the scarcity of certain goods. The currently prevailing elevated inflation rate reflects the scarcity of precisely identifiable goods in the statistics, which will not persist in the long term and will certainly not continue to increase, as would be the prerequisite for inflation intensifying without wage pressure. There is no question of such a scenario in Germany and Europe. But if such a process were to really occur, it would certainly be the poorer part of the population that would be hit by the then unavoidable intervention of the ECB via rising unemployment.