There are answers given by politicians to journalists’ questions that are stereotypically repeated hundreds of times, and although each of the answers is completely meaningless, they are never followed up. So, it is with the debt brake for Germany and Europe and the question of whether it should not be revised after the Corona shock. All defenders of the debt brake or the European debt rules (from Olaf Scholz to Christian Lindner) keep saying that no, these rules do not need to be revised because they have just proven their flexibility in the Corona crisis. In the exploratory paper of the potential traffic light coalition partners, point 10 “Germany’s responsibility for Europe and the world” literally states: “The Stability and Growth Pact has proven its flexibility.”

But that is exactly the wrong answer to what was behind the journalists’ question – only, unfortunately, none of the questioners realizes it. There was never any doubt that a rule that explicitly provides exit clauses for emergencies can actually be suspended in an emergency. That is not remarkable in any way. The fact that the get-out clause could be used has precisely nothing to do with flexibility. A rule is flexible precisely when its application can be “adjusted” without much contortion in emergencies other than those explicitly provided for in the rule.

Actually, what journalists are interested in is whether, after the use of the exit clause during the crisis, the rule is now subsequently flexible enough to give economies enough breathing room for a recovery to materialize. In other words, one wonders how countries whose debt levels are now much further from legal norms than before can reduce those debt levels without immediately facing a new recession with unemployment rising again. This important question is not answered by referring to the exit clause provided for by law, but is simply ignored.

An honest answer

The honest answer of those who do not want to change the existing debt rules would have to be the admission that they will have to live with years of austerity on the part of the public sector from now on. After all, in order to bring the new debt of the German state to the level of close to zero provided for in the Basic Law or to return to the debt level of 60 percent of GDP provided for in the EU Stability Pact, the German state budget, like the state budgets of the other EU countries, will have to make net savings, i.e. systematically spend less than it takes in each year.

In this situation, anyone who wants to stimulate additional private and public investment, as the new three-party coalition in Germany is planning, would have to cut government spending that is not detrimental to investment. But there are no such cuts – not even in social spending, which would be unwise to cut for normative reasons alone. After all, every government expenditure benefits the corporate sector directly or via some detours, and every cut in such expenditure inevitably translates into declining corporate profits.

Almost the same problem arises when additional public investment is financed by higher taxes. Whenever the higher taxes lead to a cut in spending (on investment or consumption) by those taxed, their hoped-for positive effect is negligible. Only in the case where rising taxes predominantly affect those households whose savings rate is very high and who consequently offset the tax burden by a declining savings rate, the overall effect of higher taxes and higher government spending is clearly positive. This argues in favour of (increasing) wealth taxes for very rich households. But the quantitative effects are likely to be small; more important than stimulating the economy in such a measure is combating rising inequality.

The state does not act in a vacuum

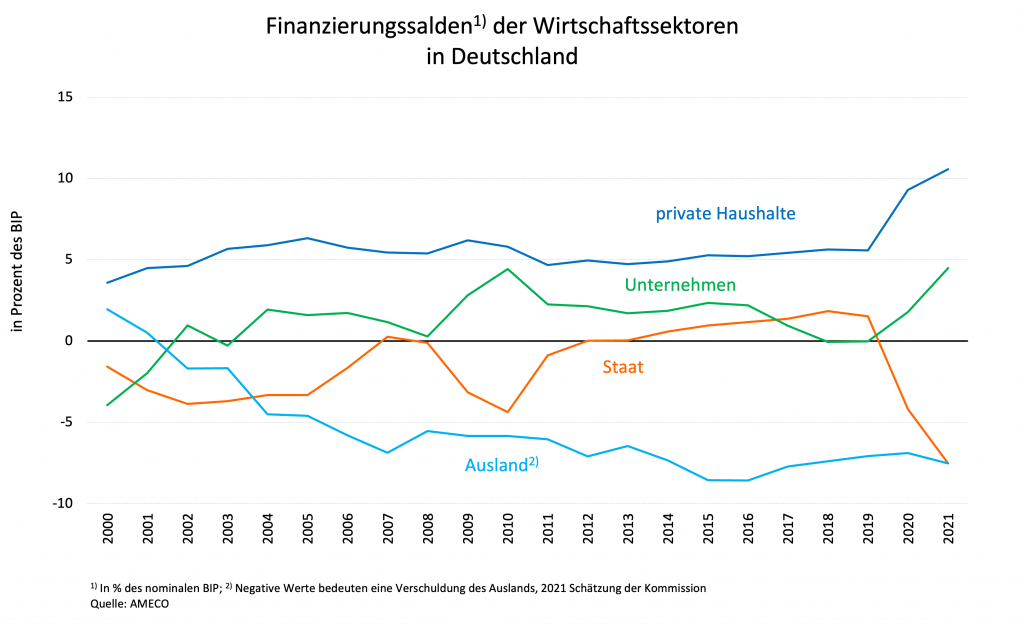

In order to assess what effects government saving has over time, it is necessary to get an idea of whether the other sectors of the economy can be expected to do the opposite, i.e. to take on (additional) debt to offset the demand-reducing effect of government saving. Figure 1 shows that neither households nor German companies can be expected to contribute in this respect.

Both sectors are net savers and are so far above the zero line that a return to a lower level of saving can perhaps be expected for next year or the year after, but not a dive into net new borrowing. Nor is there any further stimulus (such as an interest rate cut) to make high net saving less attractive. In particular, companies will not be dissuaded from their twenty-year policy of acting as net savers by such tricks as reducing bureaucracy and speeding up approval procedures for public projects. There is no way in the world that private households will be persuaded to give up their savings position, especially since citizens are being told that they have to save even more to safeguard their pensions. For example, the exploratory paper says: “A subsidy should provide incentives for lower income groups to take up these products [meaning private investment products for savings].”

Figure 1

The only way the German government can repay debt is to borrow even more from abroad. If Germany’s current account surpluses were to increase massively once again, it could use this demand stimulus for the German economy to restrain its own spending, as it has done over the past decade. But there is no factual basis for this. A real devaluation of Germany within EMU cannot be achieved again. Moreover, this would immediately reduce the chance of the other EMU countries to consolidate their public budgets to almost zero. And the hope that sounds from the exploratory paper, that not only Germany’s competitiveness but also that of the rest of Europe vis-à-vis the rest of the world could be strengthened is downright absurd. The United States would (rightly!) nip such an attempt in the bud with protectionist measures or a weakening of the U.S. dollar.

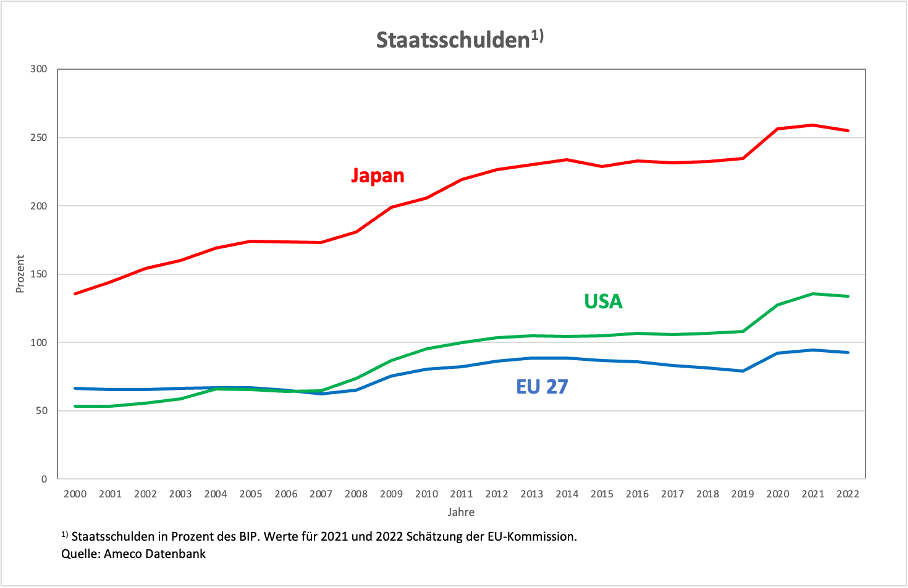

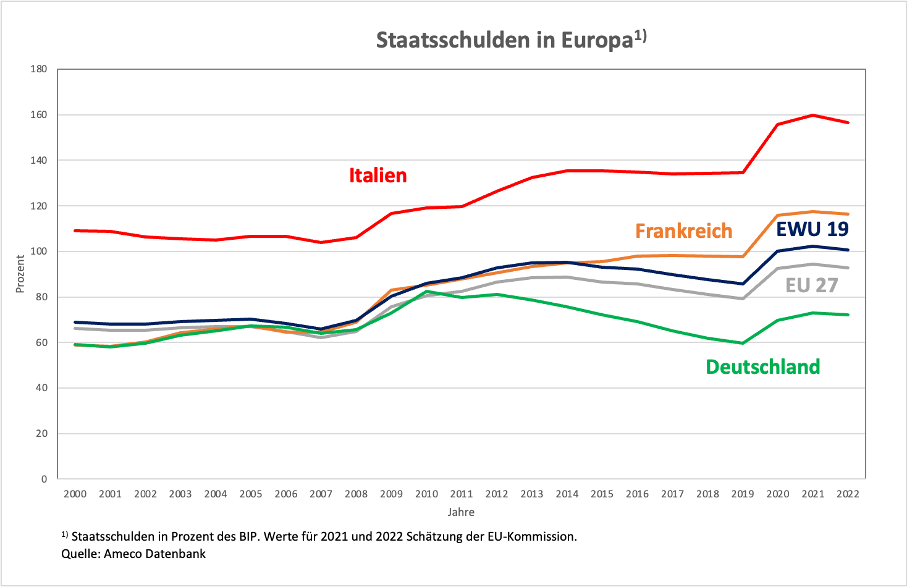

Debt levels are high, but unproblematic

Consequently, there is no other rational option than to accept and tick off the significantly increased debt levels of the states after Corona (Figures 2 and 3). Any attempt to achieve debt reduction in the next two years is bound to fail (which is why the slight downward bending of the curves assumed by the EU Commission in its debt forecasts for 2022, as shown in the figures, will have absolutely nothing to do with reality). Over the past decade, only those countries – such as Germany and the Netherlands – that have had high and rising current account surpluses have succeeded in depressing government debt.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Who is taking the bill?

The state used its monopoly over money in the Corona crisis in almost all major industrialized countries, borrowing heavily itself at low interest rates, thus preventing a much deeper crash of the economy. It cannot do this all the time and in almost any way it chooses. But it must be able to do it whenever there is a serious crisis, especially one that has been triggered quite specifically by the state in response to a health risk to large parts of the population. It must be possible to respond to such an emergency situation completely independently of the current level of debt. The case of Japan shows that this is possible: in 2020, Japan increased its debt level by 21 percentage points from 235 percent of GDP in 2019 to 256 percent (an increase of 10 percent) and will accumulate around 3 percentage points more in the current year. This has obviously not harmed its credit rating on the financial markets, as evidenced by interest rate levels and exchange rate developments.

The government’s response to the emergency situation in the form of a sharp increase in debt now in no way justifies burdening certain groups of society far more than others with the attempt to repay the debt. But this is precisely what happens when tax increases are ruled out and government budgets are “combed through” (in many cases in the “tried and true” manner) to eliminate such public spending as is obsolete in light of certain political ideas. The result, as proven time and again in the past, will be a burden on those groups of society that can hardly defend themselves because they are poor and unorganized.

The argument that has been heard again and again for decades, that subsidies can be cut, is also nothing more than a smokescreen intended to make it appear that companies are also being hit by government cuts. Subsidies always secure jobs in some way, and pointing this out has regularly succeeded in nipping any political initiative to cut subsidies in the bud in the past. In other words, the announcement of subsidy cuts lacks credibility. The suspicion is that it is only made in order to make impending cuts in the social budget look less one-sided. After all, without such cuts, the plan to spend 50 billion euros a year on sprucing up the public infrastructure while complying with the debt brake and at the same time not raising taxes is like trying to square the circle.

Those who do not want to further divide society must refrain from any attempt to use the expenditure side of government budgets to gain the leeway to reduce public debt. If the Greens and the SPD get involved in the FDP’s game with the fate of those who are financially dependent on the state in one way or another, their claim to want to ensure a reduction in glaring inequality is invalid from the start. Those who fail to reform the debt brake and the European Stability Pact are sinning against future generations. Because they will leave behind a society that not only lacks the necessary infrastructure but, far more importantly, a society that lacks any social cohesion.