In the past, there were still recessions in the economy. These were phases of shrinking gross domestic product (GDP) that lasted two, three quarters or a whole year. Rising unemployment and shrinking incomes were practically always the result. And monetary policy always had to lower interest rates and the state had to intervene by increasing its own (debt-financed) spending if it wanted to prevent worse, namely a total crash.

To take away the horror of this phenomenon, the “technical recession” was invented a long time ago. If GDP falls for two quarters in a row, it is called a technical recession. But since it does not matter whether GDP falls twice by 0.1 percent or twice by five percent, this categorisation says nothing at all. What always matters is whether there are forces that counteract a crash once it is underway and prevent a very big crisis.

There are rumours that some form of recession is currently looming in Germany, but the professional optimists in the German media and in German economics have quickly invented a whole new form of recession, the “winter recession” or even the “mild winter recession”. Winter is apparently meant to suggest that we are dealing with a seasonal phenomenon that disappears of its own accord as soon as the sun shines again. Winter recession also sounds as if it is the nasty cold winter that brings us a recession and not an economic policy that has completely lost its way.

Of course, the “winter recession” includes a positive interpretation of all indicators. The signs, one hears everywhere, are still pointing to positive surprises for Germany, even if some things are pointing downwards. But the augurs are wrong. All the signs are pointing to recession and, what people would prefer to let go completely unnoticed amidst all the talk about the “shortage of skilled workers”, they are also pointing to rising unemployment.

Since we already know that monetary policy in Europe is exacerbating the crisis instead of fighting it, this recession, even more than most of its predecessors, has the potential to turn into a major crisis, the consequences of which will be felt for many years to come. In addition, the threat of a recession immediately after the end of the great Corona slump makes matters much worse, because it does not solve Europe’s already long-running problems, but again puts them on the back burner.

For all these reasons, the downplaying of the downturn by the professional optimists is simply irresponsible. Those who persuade economic policymakers that everything is not so bad and will somehow sort itself out are serving certain ideological positions (“the market helps itself and you don’t need the state”), but they are probably doing enormous damage.

Why we are all poorer

Let’s start where it all originated. This recession, as I said some time ago, is the result of global redistribution, which in turn can be traced back to the shocks in the fossil fuel markets. Consumers in the countries that buy and consume fossil fuels are being asked to pay for the benefit of those who sell them. Real incomes in our country (for workers and for entrepreneurs) are shrinking because the oil and gas bill has risen enormously. Consequently, there is less income available for the purchase of consumer and investment goods produced by us or by our European neighbours.

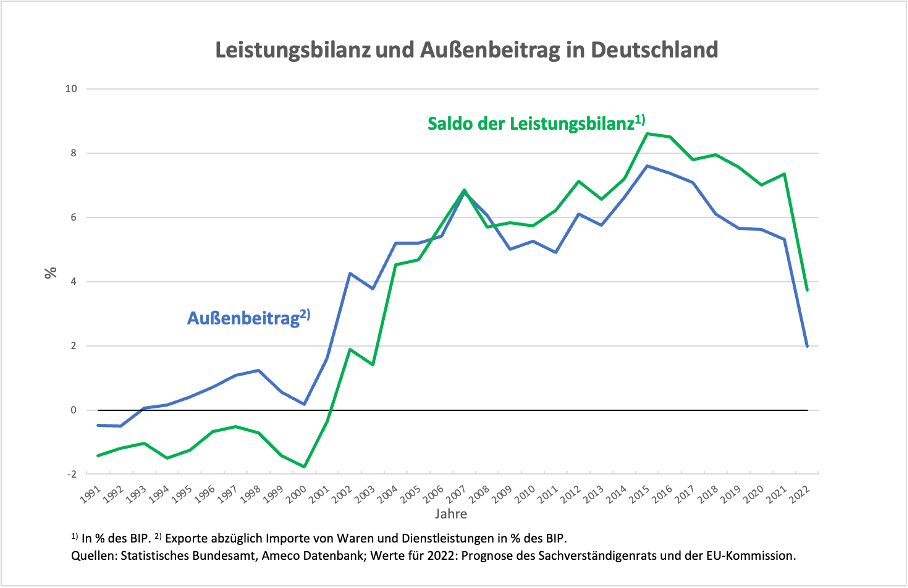

You can see this directly in Germany in the current account surplus, which will have shrunk by about half at the end of this year (Figure 1). That is a sum in the order of 140 billion (or just under 4 per cent of nominal GDP) that is simply gone and no longer available for distribution domestically.

Figure 1

Because there is this negative terms-of-trade effect (the TOT effect results from the fact that import prices rise much more than German export prices), the bargaining partners cannot simply pretend in their negotiations that the price increases measured domestically benefit German companies in full.

Those who come to the conclusion that wages must rise strongly in view of the current price increases according to the formula “current inflation rate plus productivity growth” in order to secure demand are totally wrong (the Financial Times has also failed to understand the significance of TOT losses for wage development). The TOT effect acts like a reduction in productivity and must be accounted for accordingly at a discount.

Wage increases based on the current inflation rate and productivity trend without considering external pressures would undoubtedly lead to new and permanent price increases. These, in turn, would be taken by monetary policy as a reason for even more restriction via rising interest rates and this would – again without any doubt – result in even higher unemployment. However, it must be said that the major agreements reached in Germany in the chemical and metal sectors a few weeks ago were a good compromise between permanent wage increases for the next two years and one-off payments.

What do the indicators say?

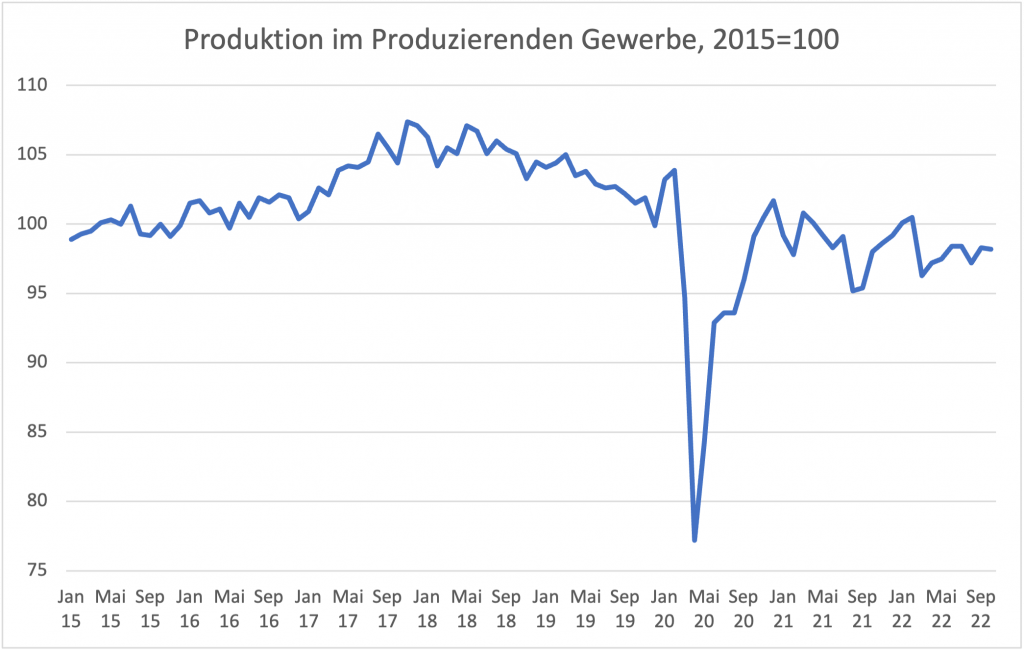

In the case of industrial and construction output, the downward trend that has been observed since the beginning of 2021 continued in October (Figure 2). Production had already been trending downwards since the beginning of 2018. After the slump in spring 2020, production recovered but lacked any positive momentum.

Figure 2

Source: Federal Statistical Office

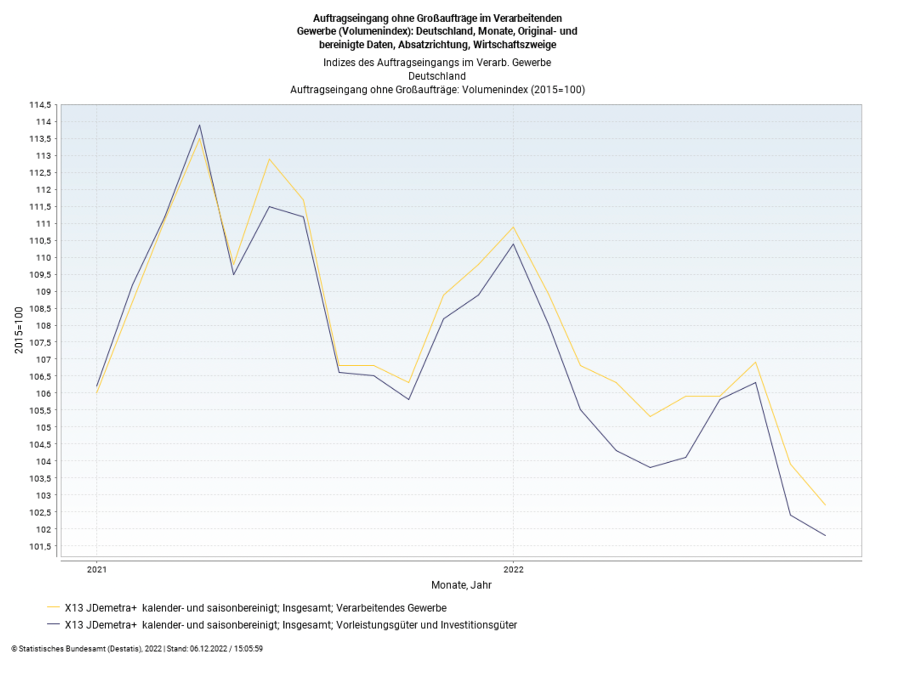

New orders in industry and construction, which point a little further ahead than production, are also clearly on a downward trend. Last year there was a brief upswing here, during which the huge losses during the Corona shock were partly made up. Since the beginning of this year, however, things have clearly gone downhill (Figure 3). Domestic demand for capital goods is particularly weak. Here, the value in October is ten percent below the level at the beginning of the year. Just a reminder: institutes, the Council of Economic Experts and the government are counting on an investment upswing next year (as shown here).

Figure 3 (original image from the German Statistical Office)

Things are much worse in the construction industry, which is already in the midst of a severe slump. Demand has fallen by a total of 30 percent in building construction since the beginning of the year. In residential construction, demand has plummeted by a whopping 40 per cent after peaking in March, even though there is a general lament about the lack of hundreds of thousands of affordable homes. However, there are supposedly still “expert” observers who believe that interest rate hikes in general, and especially such small ones as this year, have no negative effect on investment activity.

This picture is also confirmed by the assessment of the current situation in the monthly survey of the ifo Institute. This continued to fall in November across the economy as a whole, as it had for several months before. However, the media have pounced on the overall value of the ifo index because it has recently risen again slightly. This is a misinterpretation, however, because companies’ expectations for the next six months have improved. However, these expectations are at an extremely low level (almost as low as at the lowest Corona point), where fluctuations on the scale of November have no significance for the current development. The assessment of the situation in November was worse than before the Corona crisis.

The consequences of the loss of workers’ buying power can be seen directly in retail sales. Retail sales plummeted in October and have been declining since the first quarter compared to the previous quarters. The positive effect expected by many of a decline in the household savings rate, which had risen sharply during the Corona shock, is obviously being eclipsed by the loss of income, so that on balance most households have reduced their consumption in the course of this year.

Finally, unemployment has risen sharply in the last three months and the number of job vacancies has fallen significantly. Underemployment (unemployed plus those employed in special measures by the Federal Agency) has risen (seasonally adjusted) by an average of more than 30 000 persons per month over the past four months. The number of registered vacancies has fallen significantly month by month during this period – by 7,000 in November and by 17,000 in October.

Does economic policy give support?

In a constellation where private demand in Europe is inevitably falling because of temporary price and terms of trade effects, the ECB’s policy is, I can only repeat myself (last described here), totally inappropriate. How inappropriate has just been impressively demonstrated by the ECB’s chief economist (who, by the way, was a voice of reason for a long time but then completely fell over). We should not expect monetary policy to have an immediate effect on financing conditions, he said at a recent event. However, monetary policy does have the effect of sufficiently tightening financing conditions over time, dampening demand and weakening price pressures.

This statement only makes sense if one believes that price pressure has something to do with demand, i.e. with “too strong demand”. However, if one is hoping for demand to be weakened by monetary policy in order to dampen price pressure, one is currently on the completely wrong track. Price pressure has nothing, absolutely nothing to do with demand, but solely with the shocks mentioned at the beginning. These shocks dampen demand by themselves, so there is no need for additional dampening by the ECB. How does the ECB know that only its additional dampening will push demand down far enough to reduce price pressures?

Because the ECB is doing exactly the wrong thing, the state’s task is even more difficult. If it wants to prevent a deep crash of the economy, it must not only fill the gap that stems from lower domestic demand and is reflected in the lower current account surplus, but also the one that is additionally created by the ECB by reducing investment activity. This is almost impossible. But a forward-looking policy would try to prevent a severe slump through a pronounced anti-cyclical policy. However, there can be no talk of this in a government that is pushing for compliance with the debt brake to the very end. At the top of this government, there is simply a lack of the expertise needed to pursue an appropriate macro policy. Unfortunately, neither official nor unofficial advisors are to be seen far and wide to help it along.