The months of talk about a “winter recession”, a “technical” or “mild” recession in Germany, which will be overcome in the course of the year, has come to an end. The indicators are now too overwhelming and the criticism from the employers’ camp too loud for those responsible for economic policy and the media to gloss over the downward trend of the German economy .

The negative development had been apparent for more than half a year, as can be read here in an article from early December 2022. The recession is due to a lack of demand: the mass of the population – this applies to Germany as well as to half the world – has less purchasing power this year than last year; real incomes have fallen because prices for energy and many foodstuffs have risen sharply.

The loss of purchasing power also occurred at a time when the economy was just beginning to recover from the effects of the Corona pandemic. Companies in many sectors, as well as workers, had therefore already gone through a lean period and had not built up any cushions from a previous boom, as is the case in “normal” business cycles at the end of an upswing.

Between the start of the slump and the government’s admission that the economy was doing poorly, a lot of valuable time has passed that could and should have been used to stimulate the economy positively. What weighs particularly heavily: The lack of demand, caused by largely exogenous factors and based on price surges, is being massively reinforced by European monetary policy. In addition, there is a pro-cyclical fiscal policy in Germany, i.e. the state’s attempt to save and spend less precisely when there is too little demand overall. The interaction of these factors has what it takes to turn an economic downturn into a protracted recession.

These two serious mistakes in economic policy must be identified and corrected quickly if we want to turn the economic tide in the short term in order to avert a worsening negative trend. But the prevailing doctrine in economics is aiming in exactly the wrong direction. The Handelsblatt asked ten German economists what, in their view, needs to be addressed as a matter of urgency. With the exception of one, the answers do not even indicate an attempt at a macroeconomic analysis. The respondents ignore the central economic policy reasons for the economic deterioration. What is mainly stated in the advice refers to framework conditions (“Ordnungspolitik”). That does not have to be a mistake, but it doesn’t really address the causes of the current imbalance and therefore it doesn’t promise a cause-related and timely solution to the problems.

Europe-wide investment weakness

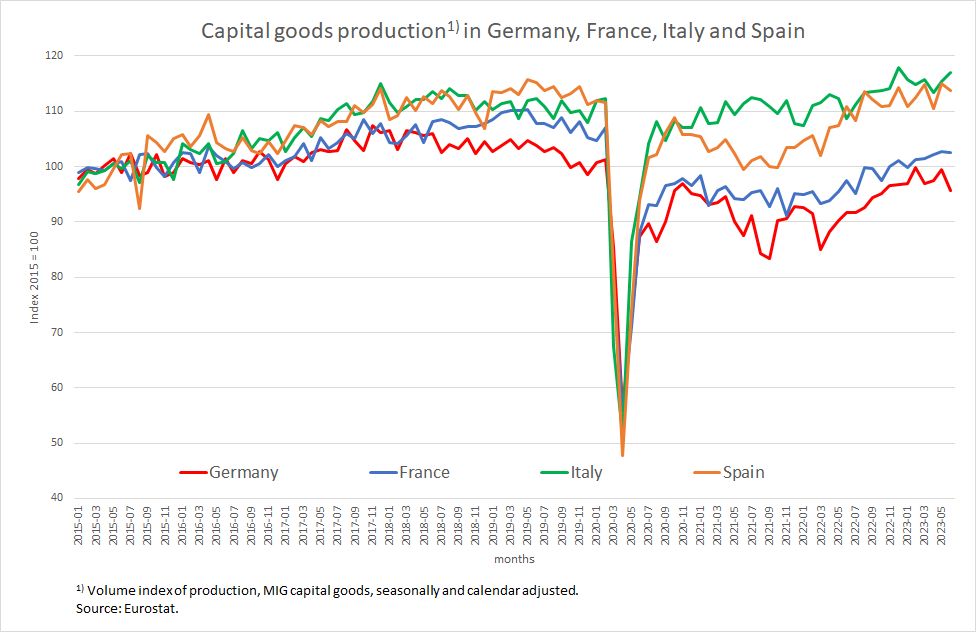

If the ECB explicitly states its goal of dampening demand through its interest rate policy, one should not be surprised if it succeeds in doing so through a brutal approach, as it itself stated in its most recent press statement on its interest rate decision at the end of July. The ECB has also emphasized that this policy aims to lower the rate of increase in consumer prices. However, since the cause of the price surges over the past two years, as we have shown in many articles, is not excessive demand driven by high wage increases, it cannot be meaningfully remedied by curbing demand. What the ECB is doing in pursuit of its price target is tantamount to a Pyrrhic victory: the European economy is now making up in investment weakness for what the energy and food price crises have done to demand (Figure 1).

Figure 1

The two largest EU countries, Germany and France, are producing capital goods at the same volume level as eight years ago, less than at the time before the pandemic shock. And this despite all the funding programs (e.g. Green New Deal or NextGenerationEU) and positive institutional course-setting (e.g. EU taxonomy) on the part of governments and the EU.

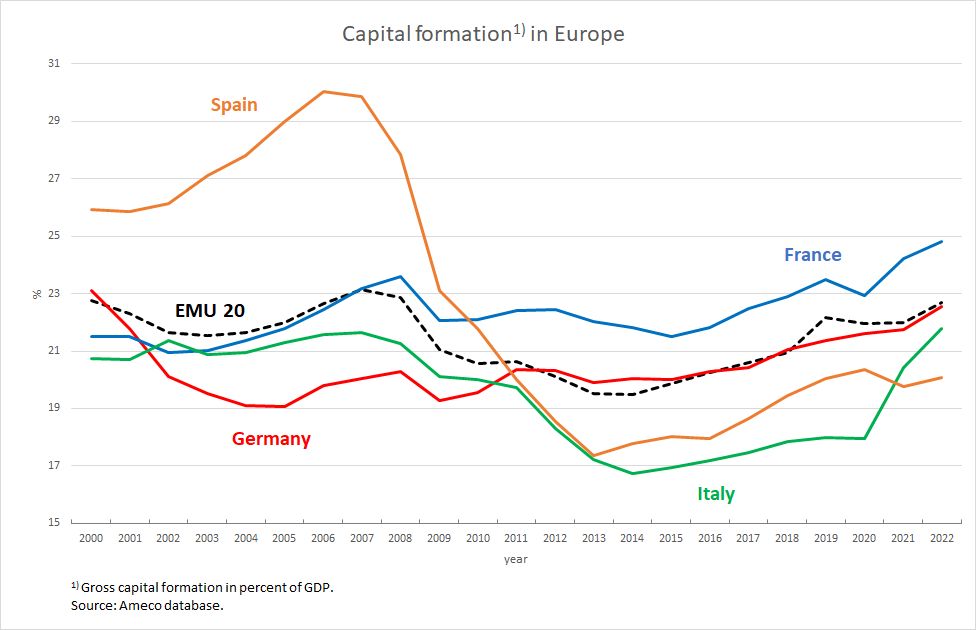

Italy and Spain have now returned to their 2019 production levels in the capital goods sector. But this level had plummeted in the course of the euro crisis in 2013 and had recovered only slightly by 2019, as a look at the investment ratios shows (Figure 2). In this respect, the starting point of the capital goods production index shown in Figure 1 is modest and therefore the current improvement in both countries by no means reflects a boom that would indicate an overcoming of the European investment weakness.

Figure 2

In addition, the production of defense equipment is included in these data. However, as is well known, the increased government demand for military goods is not an indicator of future productivity gains in the civilian sector and in this respect is not encouraging when it comes to the medium-term prospects for European real income development (see below for more detailed data for Germany).

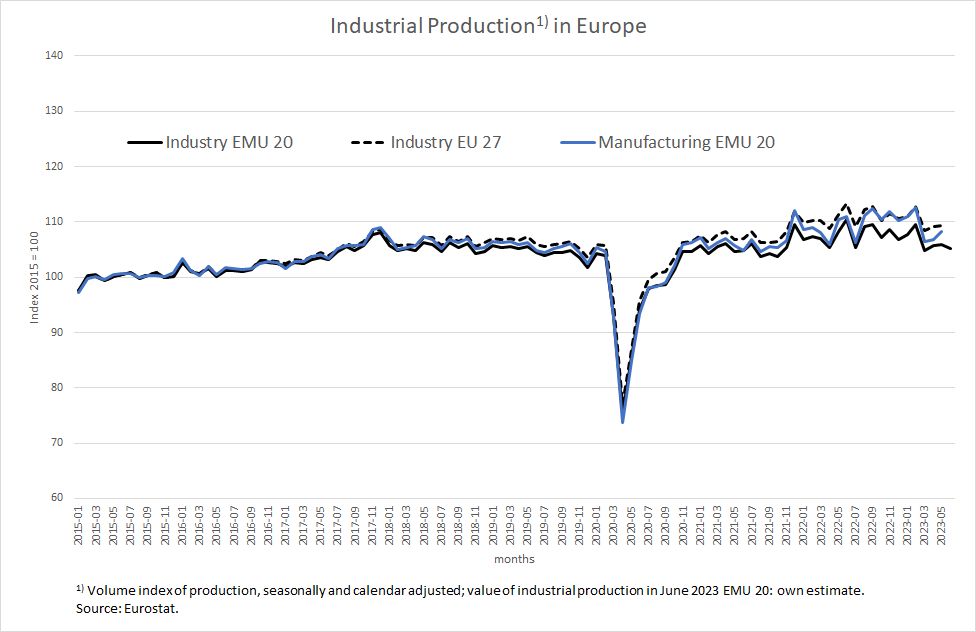

Looking at industrial production as a whole, the picture for the EU and even more so for the EMU is one that can at best be described as long-term stagnation (Figure 3): The slump in spring 2020 due to the pandemic-related lockdowns was more or less made up for within the same year. In 2021, production bobbed along at the recovered level. In 2022, the situation improved slightly on average compared to 2021. Since then, even this small progress seems to have disappeared and industrial production in the EMU has fallen back to the 2019 level.

Figure 3

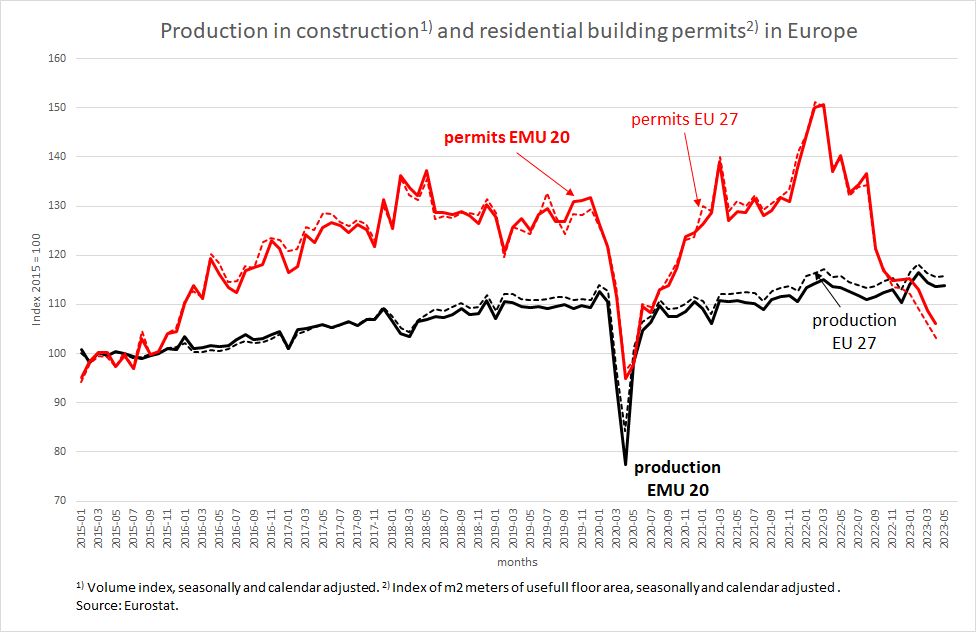

Construction sector on a downward slide across Europe

The economic slowdown is also already making itself felt in construction output (the black lines in Figure 4). However, the slump in permits for residential construction is particularly striking (the red lines in Figure 4). Here, Europe is on a path reminiscent of the 2020 crisis – only this time it was not a government-imposed production stop that caused the crash in permits, but the ECB’s interest rate hikes.

Figure 4

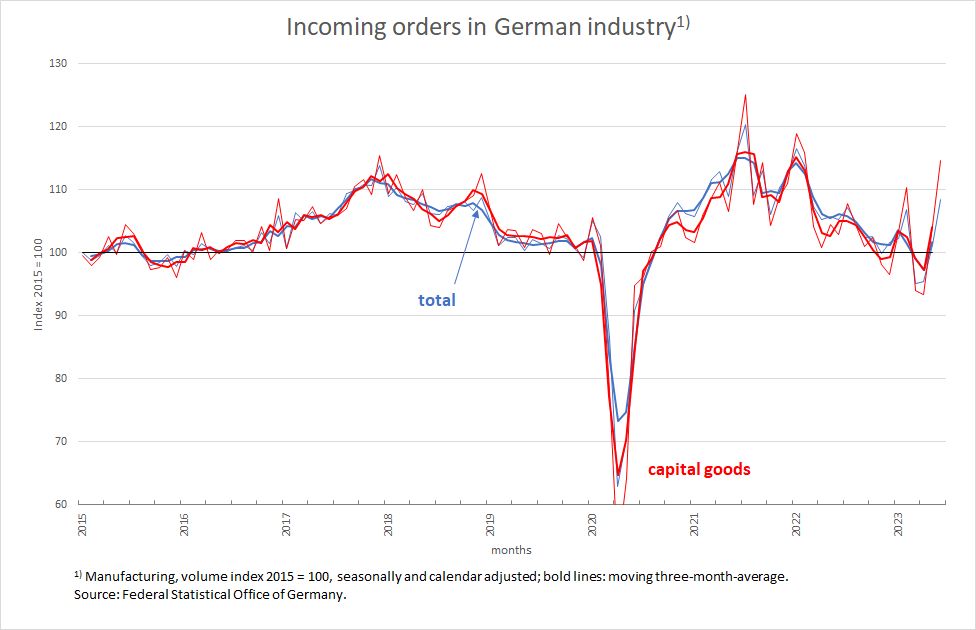

Demand for German industrial products without bulk orders continues to plummet

The indicator of incoming orders, which unfortunately does not exist for other European countries, confirms the bleak picture of the German economy. Looking at the three-month moving average, both for manufacturing as a whole and specifically for demand for capital goods, are at the same level as in 2015 (Figure 5).

Figure 5

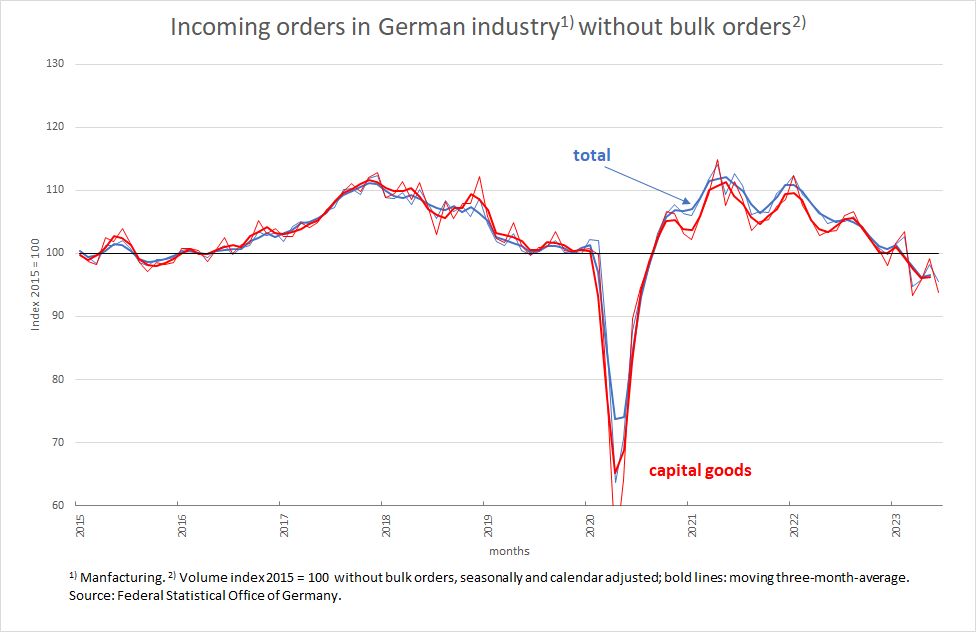

If one excludes bulk orders (Figure 6), the downward trend is also obvious at the current margin. Since government demand for defense equipment is likely to account for a large share of the bulk orders, the incoming orders adjusted for bulk orders probably paint a more realistic picture of the prospects for German industry. Moreover, these figures only cover the period up to June. Sentiment indicators such as the ifo index and the PMI Markit are already signaling a further significant weakening for July.

Figure 6

If the opposition now speaks of Germany’s de-industrialization and attributes this, for example, to a declining share of manufacturing in total production, they are wrong. The capital stock for industrial production exists and is not generally ailing – it is currently lacking capacity utilization. It is true, however, that if a state of underutilization persists for a longer period of time, capacities are not renewed and become obsolete accordingly.

Conversely, the Chancellor’s assertion that the settlement of semiconductor factories in Germany proves the attractiveness of the location shows how helpless politicians have become in the meantime. For behind these new investments, such as in Magdeburg (Intel) or Dresden (TSMC), there are between 30 and 50 per cent state subsidies of the total planned investment sums. A subsidy race is taking place here worldwide, but also within Europe, which raises not only questions of fairness, but above all the question of how much individual, globally active large corporations now have democratically elected politicians in their hands.

Pyrrhic victory of monetary policy

The fact that the price increases observed since 2021 have nothing to do with excessive demand, but with supply bottlenecks and speculation, is not recognized by the majority at the top of the ECB as a signal to evaluate and treat the price surges differently than with conventional interest rate policy. At a time when demand is weak across Europe and a recession threatens in Germany, hitting demand is monetary policy without sense and reason. Especially since, as we have shown many times (most recently here), there is no longer any ongoing inflationary pressure.

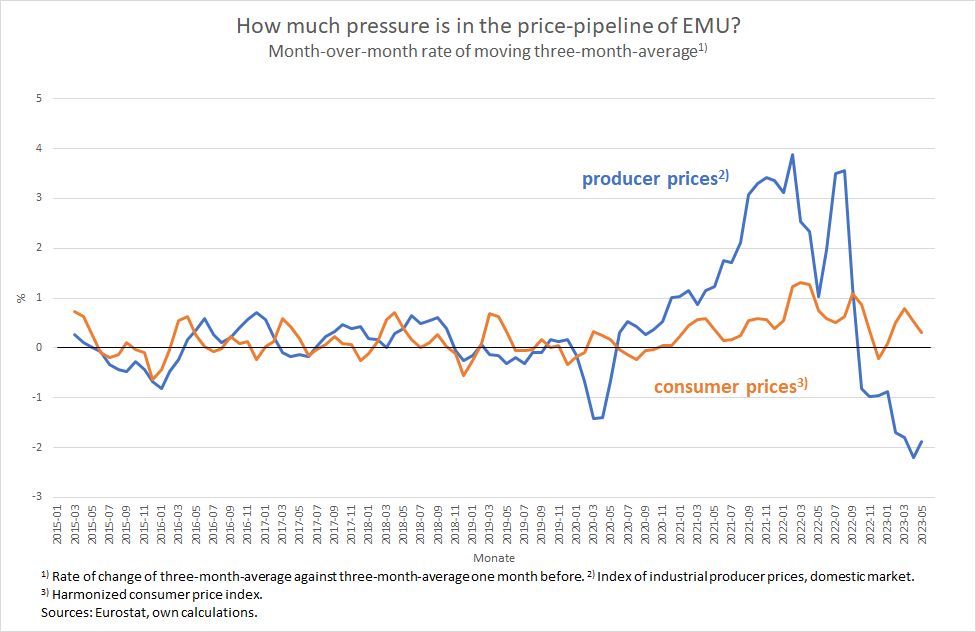

Figure 7

This is particularly evident in Figure 7, where the current rate of change, i.e. the rate of change from one month to the next (and not compared to the previous year) of producer prices and consumer prices in the EMU 20 is shown – based on a three-month moving average. The three-month average smoothes out the indicator’s short-term ups and downs making it easier to see the underlying trend.

It is easy to see that the extreme upward swings in producer prices between autumn 2020 and autumn 2022 are now followed by extreme downward swings. It is only a matter of time before consumer prices follow producer prices in movement – and without any further stalling of the economy by monetary policy. The last four months show a rate of change of consumer prices that, extrapolated to an annual rate, is already down to 2.4 per cent. Those who talk about “price pressures” being relevant for the future must look at this rate and not at the backward-looking comparison with the previous year’s value.

Producer price increases have disappeared at a time when monetary policy was just beginning to end its zero interest rate policy (from July 2022). This means that the interest rate policy had not yet been able to unfold its effect by increasing the cost of loans and by decreasing demand until the desired dampening of price increases was achieved. It was therefore not the cause of the price calming at producer level. The ECB itself assumes a lag of at least four quarters before its interest rate policy can be felt in prices. Everything that monetary policy has now done to dampen demand could and should have been spared. For the effects of the massive interest rate hikes only gradually come into play and hit a Europe that has been economically weakened by the pandemic and the Ukraine war and which – in contrast to the USA – will now not experience a soft landing in the economy and on the labor market.

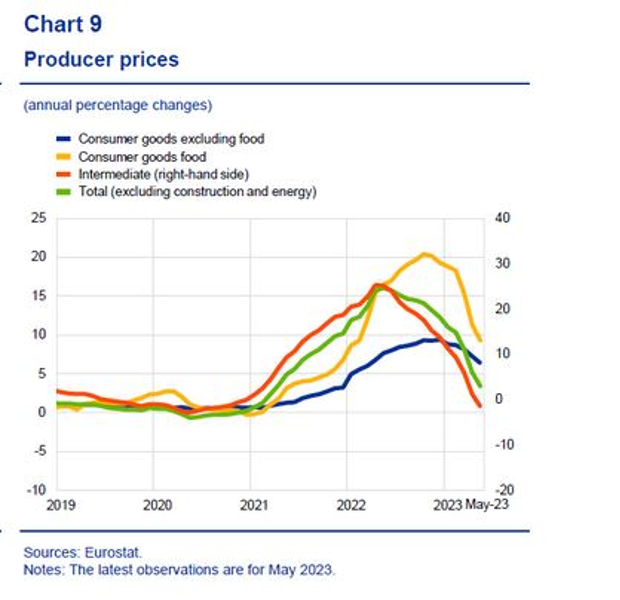

Surprisingly, a few days ago a member of the ECB’s Executive Board also pointed out that there is no longer any reason to fear price pressure. In a remarkable lecture in Italy, Fabio Panetta made it clear that he no longer sees any acute risk of inflation. He said: “Inflation pressures at the early stages of the price formation process are easing, with producer price inflation (PPI) declining further in recent months.” And he shows a picture of producer prices (Figure 8) that is exactly what we have been citing for months.

Figure 8

However, as long as the majority of the ECB’s top officials stick to the position that they have to continue to fight persistent inflation, it will be extremely difficult for the other areas of economic policy to bring about a turnaround in economic development. Even if the ECB does not raise interest rates further in September, the interest rate level now reached will make it very difficult for fiscal policy to overplay the restrictive interest rate effects. Only a truly massive fiscal stimulus to demand, as in the US, could achieve anything. But Europe is far from that given the shackles it has put on itself.

Fiscal policy as a savior in times of need?

And this brings up the second area where mainstream economics, especially in Germany, is standing in its own way. The debt brake enshrined in the German Constitution is proving to be what it always was when viewed with an open mind, and what is becoming clearer today than in all the years since its introduction: it is almost always an obstacle to a rational fiscal policy that can be flexibly adjusted to current developments. Fiscal policy is not only about government intervention in emergency situations caused by exogenous factors. Rather, it is about keeping macroeconomic development in balance at all times in such a way that a downward spiral caused by mutually negatively influencing individual economic rational behavior – regardless of what actually triggered it in the first place – is prevented.

At this point, the neo-liberal world view of an economy that controls itself sensibly through market equilibrium tendencies, in combination with a state that is as restrained as possible, collides with reality. In reality, unexpected shocks occur all the time which have to be processed in the economy and entail adjustment processes that are anything but equilibrium or balanced. Rather, they can develop a momentum of their own, the consequences of which are so negative for everyone together that state intervention to stimulate the economy is not only justified at some point, but is immediately necessary. If economic policy in such a situation behaves pro-cyclical – possibly for ideological reasons – it becomes part of the problem and not the solution. No one should be surprised that this increases the population’s disenchantment with politics.

Among the economists interviewed by the Handelsblatt, only Jens Südekum openly addresses the dilemma of German fiscal policy. Although he does not advocate for a formal abolition of the debt brake, he argues for a further suspension through the renewed application of the emergency clause. And he advises the use of loan funds from the Economic Stabilisation Fund for unspecified industrial policy programs. The latter can be viewed quite critically, both because of the time factor and because of the distributional effects. But at least someone is addressing one of the two central levers at stake in fighting against a recession.

Almost all other respondents are in favor of measures aimed at reducing costs for companies (improved depreciation, tax cuts, direct electricity price reductions, expansion of the electricity supply to reduce electricity prices, expansion of the labor supply to curb wage costs, direct wage subsidies, efficiency gains through tougher competition for qualified workers via greater transparency in pay). They obviously hope that this could noticeably stimulate companies to invest. Even if one disregards the time lag of such measures, this approach must be considered a failure in many cases.

Whenever the red carpet has been rolled out to profit earners in the past to encourage them to invest, nothing could be aligned in the long run if there was a lack of demand. This also makes sense: Who benefits from falling costs if capacity utilization is neither currently right nor improving in the future? The huge tax cuts for companies in Germany at the beginning of the century did not create any investment dynamics, but rather brought about a behavior of companies that directly calls the market economy into question (as shown here, among others).

Economic stimulus from abroad via free trade agreements as one of the proposals from the experts is also an old hat. Any stimulus through free trade fizzles out at the latest when foreign countries either have economic problems of their own and/or are no longer willing to tolerate the price competitiveness of a trading partner (i.e. Germany) that has been stifling them for years.

The fact that none of the economists interviewed by the Handelsblatt criticized monetary policy speaks volumes. That only one questions the debt brake clearly shows the decline of macroeconomic thinking in Germany. It is no longer surprising that no one mentions an unorthodox instrument that could be used to cushion the weakness in demand. Against the vote of the minimum wage commission, the state could raise the minimum wage so much that the lowest incomes would no longer suffer a real wage loss. Companies would initially complain vehemently about this, but it would benefit them one hundred per cent, because minimum wage earners would spend all their entire income on goods and services. In addition, the controlling effect of high and rising fossil fuel prices would not have to be set aside for social reasons.

But instead of a sound analysis of the macroeconomic situation and a correspondingly adequate economic policy response, many seem to be more concerned with using the current misery to enter the race on cherished hobbyhorses and to push through their own interests.