A 15-member scientific and political commission is currently beginning its work in Berlin with the aim of making proposals on whether and, if so, how the German debt brake can be reformed. Surprisingly, not one of the 15 people appointed by the Federal Minister of Finance has ever attempted to analyse and discuss the government’s debt balance as part of a larger context at the macroeconomic level in their scientific or political work.

This is more than surprising. Anyone who examines the state and its debt balance in isolation assumes that the state has no influence on the economy as a whole and that the economy, including foreign trade, has no effect on the state. This is obviously wrong. Precisely those who complain that the state has become too big and is exerting its power in all areas assume in their financial analyses that the state plays no role. Conversely, the influence is even more obvious. The state must respond to deteriorations and improvements in the economic situation because its revenues and expenditures (and the election results of politicians) depend directly on them.

The best and most logically compelling way to link the state and its debt level to the rest of the economy is through what are known as sectoral financial balances. They show at a glance how the revenue and expenditure deficits of individual sectors are interrelated throughout the economy and throughout the world. Anyone in this world who wants to achieve a surplus of income over expenditure, i.e. who wants to save (i.e. live below their means), needs a counterpart somewhere in the world who does exactly the opposite, i.e. spends more than they earn (i.e. living beyond their means). If they cannot find such a counterpart, they must cut back on their savings plans, or the overall economic income (and their income) will fall to such an extent that they will be forced to reduce their savings plans.

The world as a whole can only ever spend as much as it earns and, this is the part that many people do not understand, it can only earn as much as it spends. The world cannot live either below or above its means. Only individual countries can have surpluses of income over expenditure (current account surpluses), which are necessarily offset by current account deficits in other countries. The state must ensure that savings plans on the one hand and the willingness to take on debt on the other lead to overall satisfactory economic development. This means that the state can never assess and evaluate its debt situation in a rational manner if it does not know or does not take into account what is happening in other sectors.

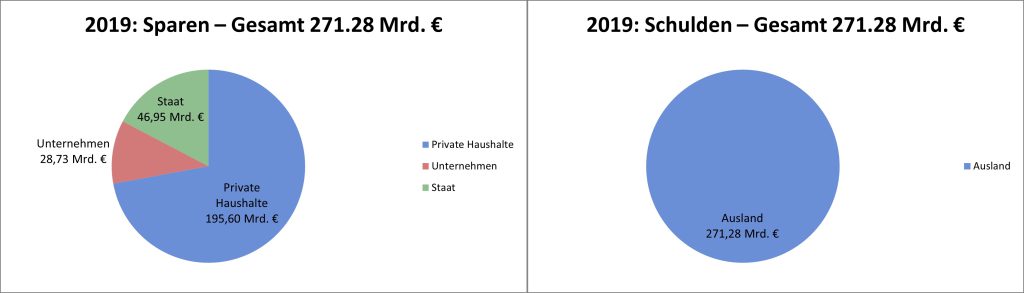

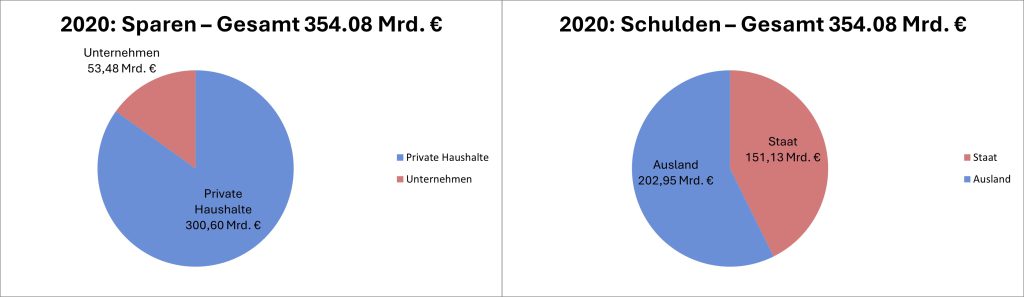

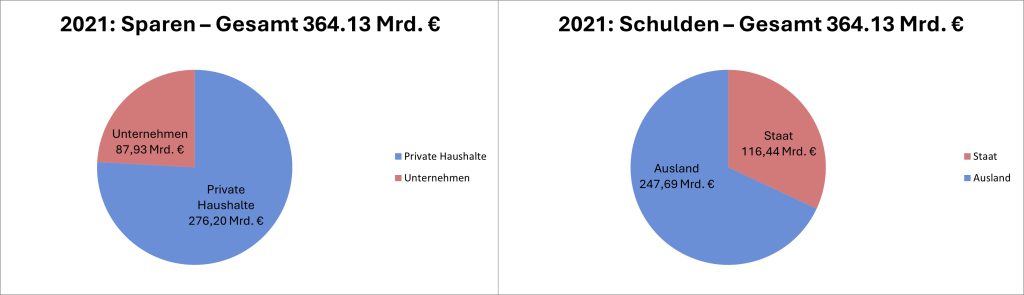

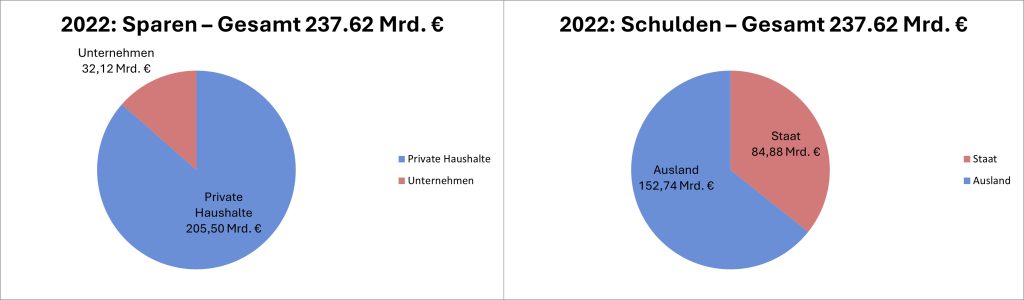

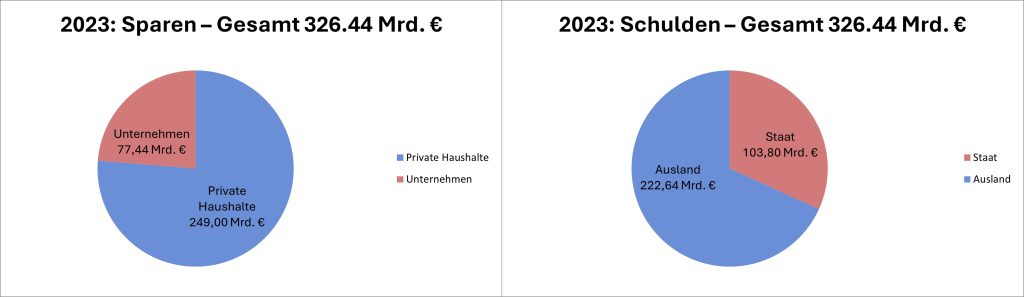

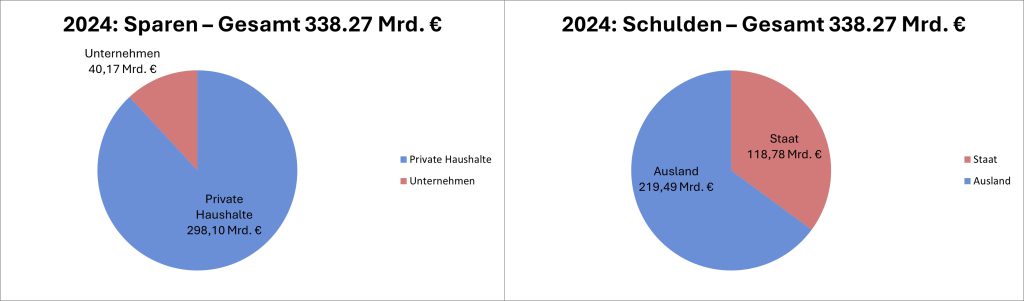

Since the 1950s, the Deutsche Bundesbank has been calculating the financing balances for Germany on the basis of national accounts and other available indicators (albeit with total disregard by the top officials). The latest calculation dates from June of this year and covers the year 2024 as the last available result. I am trying to present the balances today in a different way so that it is clear at a glance that savings and debt are two sides of the same coin. At the same time, these images show very clearly that the state can never separate itself from the rest of the economy and that any analysis that assumes this is pointless from the outset.

The German debt brake and the European debt rules are legal constructs that have no inherent economic logic. Both systematically lead to fiscal policy actions that are damaging or unsustainable because they completely neglect the state’s crucial task of stabilising the economy.

Germany’s fiscal balances over the last five years show the enormous role that foreign debt has played in the stability of the German economy. In 2019, foreign countries were even the only net debtors (Ausland means foreign countries). Because foreign debt was insufficient, the state stepped in in all subsequent years (Staat means state or government), while German companies and private households were always net savers (Unternehmen means companies, private households are easy to translate). The widespread view among ‘liberals’ and ‘market economists’ that companies ensure that savings are turned into investments has no empirical basis and is pure ideology.

It is obvious that a significant decline in Germany’s current account surplus, as is indicated for this year, will bring the state into play – in a way and to an extent that cannot be cast in any pre-formulated legal text. Therefore, there can only be one reasonable conclusion: the German debt brake and the European debt rules must be completely abolished and replaced by rules that explicitly refer to the sectoral financial balances that each country faces.