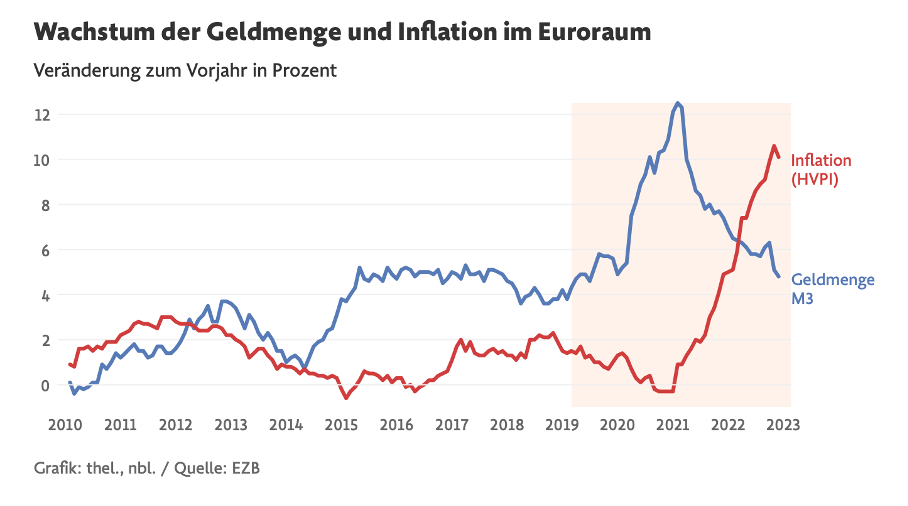

In its latest monthly report, the German Bundesbank, formally a regional branch of the ECB, devoted a long essay to the relationship between money supply development and inflation. The result is meagre. Even the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ), which is not suspected of being particularly critical of the Deutsche Bundesbank, cannot avoid giving an article on the Bundesbank analysis the title “Inflation myth money printing”. The original chart from the FAZ on this (figure 1), depicting growth rates of money and prices, says it all. In the whole of the past decade nothing dramatic has happened with the money supply (here the so-called M3), which the Bundesbank regards as the most relevant of the various money supply aggregates.

Only with the onset of the pandemic and the extensive measures that amounted to a far-reaching standstill of the economy was there a pronounced need for liquidity, but this disappeared again completely with the end of the deep slump in the real economy. That this kind of money hoarding could have something to do with the acceleration in price development that began at the end of 2021 is out of the question. This hypothesis is not even seriously put forward by the Bundesbank. However, in such a case one should not simply interpret the empirical data as if there were a theory behind it. As will be explained later, there is no such theory.

Figure 1

A close connection between money supply and inflation is claimed by so-called monetarism, i.e. the doctrine that emphasises that inflation, as Milton Friedman, one of its most famous founders, called it, is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.

The current preoccupation of the German branch of the ECB with monetarism is interesting insofar as the Bundesbank has had to experience over the past twenty years that the ECB has increasingly abandoned a concept based on this monetarist context. In contrast, the Bundesbank, after it was able to implement an independent monetary policy after the end of the Bretton Woods world monetary system, had fully built on monetarism. At the beginning of the European Monetary Union, German politicians and the Bundesbank had counted on the ECB to consistently continue this policy (the “stability culture”, as the Bundesbank calls it).

In the current phase of high price increases, where the theory of money supply is receiving new impetus from all possible directions, the Bundesbank’s extensive referral can only mean that the ECB is to be persuaded to set the course more strongly in the direction of monetarism again. That, however, would be fatal. The intellectual contortions undertaken by the Bundesbank in order to somehow save the context give an inkling of how absurd a return to this outdated view would be for the ECB.

The world in equilibrium?

The Bundesbank’s economists consistently use neoclassical equilibrium models for their work. These models are based on the idea that the entire economy is a stable (a stationary) system that has to deal with shocks, but in principle always returns to equilibrium with the help of the market mechanism. Explicitly, the Bundesbank analysis states: “The prevailing paradigm in macroeconomics assumes that an economy tends towards a stable long-term equilibrium and that deviations from this are due to shocks, i.e. exogenous impulses hitting the economy (page 24).” However, it is more than astonishing that the Bundesbank economists use a model in which the currently so decisive energy prices do not appear at all, i.e. with which one cannot analyse the currently dominant shocks at all.

The economics underlying analyses such as those of the Bundesbank assumes that there are a large number of individual markets that all tend to return to a stable state after initial disturbances that come “from outside”. The problem is that in such an equilibrium system based on microeconomic adjustment processes (the description of which goes back to the work of Leon Walras in the 19th century), it is impossible to predict from many unrelated markets whether the price adjustments in the many individual markets will add up to an overall outcome that corresponds to the objectives of governments or the central bank. The inflation rate in such a model is simply indeterminate.

Ten percent price increases on average across all markets are just as compatible with this model as ten percent decreases. This is extremely unsatisfactory because a low inflation rate is seen in the neoclassical/neoliberal policy approach as central to those in the economy who want to invest and need stable long-term prospects. Consequently, a mechanism has been sought that, completely independent of individual decisions in many markets, ensures that the overall outcome is always consistent with a relatively stable price level.

Money as a transaction limiter?

Such a mechanism could only exist if it were possible from outside the market system to influence the decisions of the market participants in such a way that an invisible hand intervenes whenever the individual decisions threaten to add up to a result that is beyond what those who bear responsibility for the functioning of the whole want. This is where money came into play. Surely, according to the idea that emerged as early as the 17th century, it should be possible to limit the number of coins on which everyone who buys or sells depends in such a way that the total amount of the value of transactions is limited.

This sounds convincing at first glance, but it has nothing to do with the reality of modern monetary economies. Two huge problems emerge. The sheer number of coins is irrelevant to the quantity of transactions because coins can be used more efficiently or less efficiently. One coin can be used for ten transactions in a given period of time or just one, because it depends on how quickly the money changes hands. Money is not consumed by the transactions, but only changes hands. The so-called velocity of money is not in your hands, even if you control the amount of coins.

The second problem is that while you want to limit price increases, in a growing economy you don’t want to limit the total amount of transactions that can take place without inflation. How can this be done? If no individual economic agent can be held responsible for the price increase it triggers by its transactions, but only the total sum of all decisions is of importance, which no individual can know, the individual will do nothing. Even if politicians (or the central bank) announce that they want to keep price level increases in check, this does not imply for anyone that they have to change their way of doing business.

These two problems are still absolutely insurmountable today. Indeed, they are even more explosive today because money no longer consists only of coins and most economic entities in a country are involved in international transactions with different monetary units for which there are no rules or target values set by any institution anyway.

The quantity equation

Bundesbank officials are nevertheless not afraid to refer to a “quantity theory”:

“The quantity theory of money predicts a stable, long-term 1:1 relationship between the growth of the money supply and the growth of the price level, that is, the inflation rate.”

This is remarkable. Behind monetarism is the so-called quantity equation, but it should not be called a theory and certainly not a theory that predicts a 1 : 1 relationship. M × V = P × Y is how the equation is often written, where M stands for money, V for the velocity of circulation of money, P for the price level and Y for real national income.

However, this is no theory, no real connection between the variables, but merely an identity without a concrete statement. V is, in fact, the variable that, by definition, takes care of the equality of the two sides, because there is always an (unknown) multiple of the money supply that “finances” the right-hand side, the nominal gross domestic product (or another income variable). The only statement that can be taken from this equation is that all transactions in a money economy are financed in one way or another.

Obviously, the left-hand side is tremendously flexible, because a multiple of a money supply generated by the central bank is always used for financing. How efficiently the economy handles money and thus how many times a money supply is turned over is something that monetary policy has no influence on and it cannot know in advance. Milkmaid calculations, in which the growth rate of (what) money is compared to the growth rate of the real economy, are therefore without any basis.

But the right side, what is financed, i.e. the inflation rate on the one hand and real income on the other, also offers no handhold. Monetary policy cannot say whether a certain action hits prices or quantities. If monetary policy raises interest rates, it is almost always directly at the expense of investment and thus at the expense of the quantity produced. Whether and how prices react to this in turn depends on many factors that monetary policy cannot influence.

Consequently, one has to make incredibly absurd assumptions to come to the conclusion that the strict control of a certain money supply could prevent prices in an economy from rising far above the inflation target. The belief that one can control the “money” relevant for inflation in such a way that inflation, if one excludes manual errors of the central bank, is impossible and at the same time all development opportunities of the national economy are preserved, is not justified by anything.

The real is given

The monetarist doctrine has “helped itself” in this dilemma by assuming that real development cannot be influenced by the money side in the “long run” anyway. Money is neutral in the “long run”. This hypothesis, now called “quantity theory”, is simply linked to the assumption, which goes far beyond the equilibrium assumption, that the real development of the economy is given. No different from a planet clearly calculable on its orbit, the real economy glides through time and space without really being able to be influenced.

That is simply crazy. It only shows the absurd way in which “theories” are constructed in economics: One makes almost arbitrary assumptions and yet blithely concludes about real developments and makes policy recommendations. Even if European monetary policy makes one mistake after another in the short term and completely ruins the investment activity of an economy, this plays no role in such a model for the “long-term” development. Even if, as has happened in many countries of the world (mostly under the guidance of the IMF) over and over again, unbelievable mistakes are made in macroeconomic management and one has to struggle with high inflation rates and chaotic currency relations, this does not really influence real development, because this is virtually God-given.

This makes the overall statement of all these “analyses” absolutely meaningless: because, according to assumptions, every economy tends towards equilibrium, the real development is predetermined and monetary policy is neutral, monetary policy can in principle do nothing wrong. If it combats a price increase that is not in line with its objectives, it is irrelevant whether the price increase is the result of real shortages, the consequence of speculation or whether there is a real inflationary acceleration that is driving itself.

It is then also absolutely secondary whether monetary policy underpins its actions with excessive money supply developments or relies directly on the interest rate effect. The Bundesbank has illustrated this nicely with two diagrams. In both cases, however, monetary policy affects what the Bundesbank calls “supply and demand on labour and goods markets”. And in both cases it is a very long way from the action of monetary policy to the real economy and then from the real economy to prices. It is obvious from these diagrams that there is precisely no direct path in any sense from the money supply or from interest rates to prices.

With any actor large enough, such as the government, one could construct a very similar picture and claim that the path from government demand to aggregate demand is the appropriate way to curb inflation or ensure rising prices. The special role of monetary policy suggested by the proponents of monetary policy does not exist here.

In the case of restrictive monetary policy, investment must always be damaged in order to exert pressure on wages through rising unemployment. Why this should make sense is beyond anyone’s comprehension. If, as is currently the case, prices rise across the board because there are temporary shortages in some important goods markets, it is precisely investment that is needed to overcome these shortages. Why cut investment, increase unemployment to depress wages, when wages are not rising excessively at all and consequently there is not the much-vaunted danger that the temporary rise in prices will lead to permanent wage increases that are not in line with the inflation target.

Who really has a direct influence on many prices?

The latter suggests, and the Bundesbank’s chart makes it easy to see, which actor acts much closer to prices and thus has a much more direct influence on the inflation rate. Wage developments, which are negotiated by the collective bargaining partners, are the real candidate for directly influencing the price level. This is mainly because a great many prices are decided here at the same time from a certain perspective. Wage negotiations, unlike negotiations on individual prices in individual markets, have a macroeconomic orientation that explicitly includes the inflation rate.

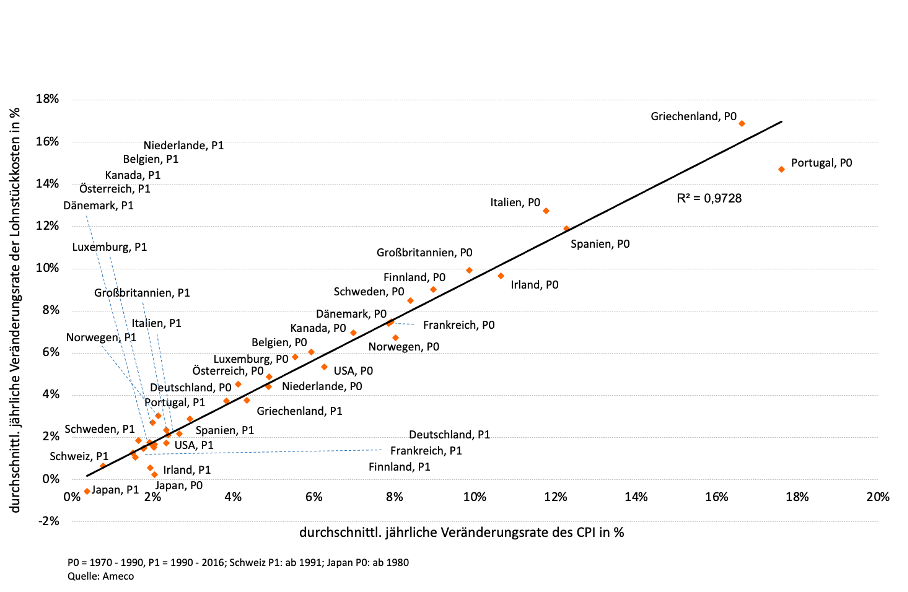

If one concedes what is empirically clear, namely that unit labour costs (Lohnstückkosten in German) have a major influence on the development of inflation and determine the inflation rate in the longer term (Figure 2), then one can also explain how processes occur in which inflation accelerates even in the absence of exogenous shocks and can take on very high values over a long period of time. Obviously, one cannot explain this with an equilibrium theory, because it is not at all about single identifiable shocks, but because there is an accumulating dynamic that is usually triggered by price surges and driven by subsequent wage adjustments.

Figure 2

Processes such as those currently taking place in Turkey, with inflation rates of between 60 and 80 per cent over many years, have nothing to do with equilibrium and shocks that temporarily disturb the equilibrium. Obviously, nothing is predetermined there in real terms either. An economics that nevertheless allows itself to be guided in its macroeconomic paradigm by the principle of a stable equilibrium and a predetermined real development simply does not want to make a contribution to explaining reality. Society may accept this as occupational therapy for detached academic circles, but when this approach is made the basis of central banks’ work, it is irresponsible because it is suggested that practical policy recommendations can be derived from such models.

The ideological background to the Bundesbank’s (and the entire prevailing paradigm’s) refusal to assign an appropriate role to wages in explaining inflation is obvious. If one were to take note of the clear empirical findings on the correlation of unit labour costs and inflation, one would have to concede that real wages cannot simultaneously balance the labour market. If inflation rates follow unit labour cost increases over longer periods, real wages rise like productivity and it is absurd from the outset for companies to base their decisions on the technology to be used on short-term deviations of real wages from productivity development, especially since these short periods are also characterised by falling demand for goods in the case of falling real wages.

If the labour market in the conventional sense no longer exists, where, as in the Bundesbank scheme above, the signals of restrictive or expansive monetary policy arrive and lead to falling or rising wages, the entire model is obsolete. In a world where wages are negotiated for large numbers of workers and an inflation rate is explicitly targeted as part of the deal to be reached, there is no need for either rising or falling unemployment to signal to the bargaining parties which direction they should move in. The inflation expectations (which need to be “anchored” in the slang of the central bankers) that central banks keep raising to a mantra are a mirage. In the real world, the central bank and the government can simply talk to the bargaining parties and make clear the fatal consequences of a negotiated settlement that in one way or another ignores the inflation target set by the government and the central bank.