Hardly anything has been written or said more in recent weeks than about the paper by Trump’s new economic adviser, Stephan Miran, which forms the basis for the so-called Mar-a-Lago Accord, a new attempt to find multilateral solutions to the global monetary system. The analogy to the Plaza Accord of the 1980s is obvious, but Miran’s attempt to find also unilateral solutions to a multilateral problem will not get us anywhere. Moreover, he is too entrenched in mainstream economic theory to come up with realistic solutions.

However, the basic approach of linking the monetary system to the trading system is entirely correct. The monetary system currently in place is chaotic, dysfunctional and not helpful for the United States, which is something no Trump critic wants to acknowledge. Trump’s finance minister, Scott Bessent, struck the right note in his first major speech a few days ago (linked below): it is about cooperation and fundamental rethinking of the global monetary system.

Triffin’s dilemma is misleading

The confusion surrounding this whole complex issue is enormous. Even the age-old ‘Triffin dilemma’ is being dusted off by many authors (including Miran) because they want to show that the US current account deficits are also essential for supplying the world with US dollars. But this is misguided. No clear distinction is made between a currency system with fixed exchange rates, as under Bretton Woods, flexible exchange rates, or a chaotic mixed system like the one we have today.

Empirically, Triffin is clearly wrong anyway. Even under the Bretton Woods system (i.e. until around 1970), when one might have expected the US dollar to be needed as a reserve currency in all countries, the US never had a significant current account deficit, as Figure 1 shows.

Figure 1

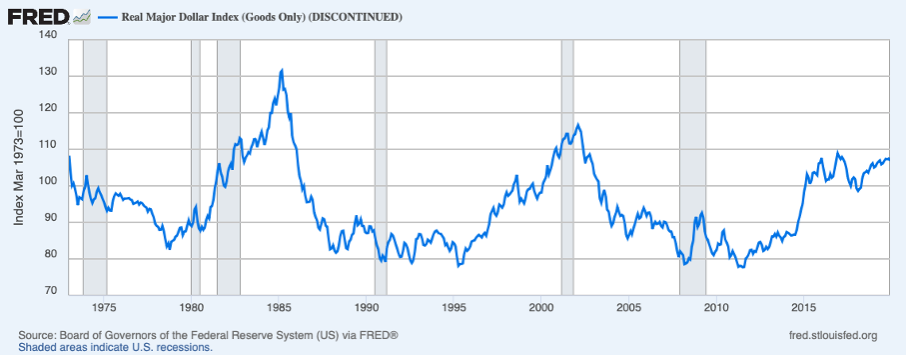

From the 1970s onwards, there were some fluctuations above and below zero, but it was not until the 1980s, as a result of a speculative-driven massive appreciation of the US dollar, that a really large deficit position emerged, which was, however, quickly corrected by the devaluation of the dollar that followed the Plaza Accord. A permanent deficit has only existed since 1990. Clearly, until 1990, the world had access to enough dollars without the dollar appreciating continuously in nominal and real terms (Figure 2).

Figure 2

The supposed privilege of the USA

The frequently heard complaint that the USA is exploiting its privilege of having a reserve currency through its persistent current account deficit is also much less dramatic than it sounds. The USA does not actually need reserves because it has the world’s most widely accepted currency. However, with a functioning system of flexible exchange rates or a well-designed fixed exchange rate system, no country would need reserves in the form of foreign currencies, because interventions in the foreign exchange market are only necessary in extreme emergencies to prevent unwanted devaluation, and the necessary sums can then be borrowed very quickly from the countries whose currencies are appreciating.

What exists today (with flexible exchange rates in most parts of the world) as ‘reserves’ is usually held by small and weak countries that want to protect themselves against speculation on a devaluation of their currencies because they cannot cope with flexible exchange rates. Reserves also include loans from the International Monetary Fund, which are backed by the United States and other industrialised countries. A separate category is made up of large countries that try to defend their currencies against excessive appreciation against the US dollar. The classic and quantitatively significant cases are China, Japan and Switzerland. In this case, it is not really a question of reserves, but rather of investments in US dollars purchased in the course of intervention on the foreign exchange markets.

This is indeed a major and absolutely serious problem for the US. Take Switzerland, for example. Switzerland has a nice ‘treasure’ of around 750 billion euros in government bonds at the central bank because the Swiss central bank has been buying dollars and euros on the foreign exchange market with printed Swiss francs for many years. This treasure has therefore been created out of thin air. From the US perspective, Switzerland has done something that harms the US, namely it has revalued less, i.e. lost less competitiveness than would have been appropriate given market conditions. At the same time, it has exchanged the francs created out of thin air for US dollars and used them to purchase US government bonds.

This is a double annoyance for the US. Now the American government is paying interest to a country that only holds government bonds because it has harmed the US through money creation. In other words, Switzerland’s wealth has been created out of thin air, but at the expense of the US, and the US has to pay for it. This is indeed unreasonable. Consequently, the proposal put forward by the Trump team to exchange government bonds held by central banks for special bonds with lower interest rates and longer maturities should not simply be dismissed as a ridiculous idea.

The accumulation of government bonds in the hands of a central bank would indeed be unproblematic if there were relatively symmetrical fluctuations in exchange rates. In that case, the central bank would sell the government bonds the next time its currency weakened and use the dollars it acquired to buy Swiss francs in order to support the exchange rate. However, francs that find their way back into the hands of the central bank are destroyed. Then the ‘beautiful assets’ would disappear overnight. But that hasn’t happened in twenty years.

The situation in China is slightly different, which shows that the US accusations are far too simplistic. The Chinese have also intervened to keep the appreciation of their currency low. At the same time, however, they have encouraged generous wage increases in the country, so that the real exchange rate (competitiveness), which is ultimately what matters, has appreciated much more strongly than the nominal exchange rate. In doing so, they have done what the US wants, but still fall through the American grid because the focus there is primarily on the nominal exchange rate and the bilateral balance with the US. However, the latter is fundamentally unsuitable as an indicator.

Only a global currency system can solve the problem

However, the cause of the whole mess is at least as unreasonable as the result, but has so far been ignored by the US. Switzerland’s currency would have been revalued beyond all reasonable limits simply because the ‘markets’ expected the franc to continue to appreciate and Switzerland to remain a ‘safe haven’ for all time. No country can allow unlimited appreciation, as the US knows better than anyone, because it then runs the risk of losing its entire industry. This shows, however, that the urgent issue here is not Switzerland’s inappropriate monetary policy, but primarily the madness of the monetary system in which we live.

A few days ago, however, the new US Treasury Secretary Bessent at least acknowledged that the basic idea of Bretton Woods, namely that a global economy needs global coordination and cooperation, is correct. This is a big step in the right direction for the US and a step away from the ‘Wall Street above all else’ mentality that has prevailed in Washington until now. Yes, it is nothing short of revolutionary to hear such words from the minister responsible in a country that has defended the ‘freedom’ of capital markets and the ‘rationality’ of currency markets like a berserker for over 50 years.

His statement that the IMF should focus on its core task and investigate and denounce trade imbalances more vigorously is also absolutely correct. He should have added, however, that the IMF must then, like the majority of top American economists, abandon the foolish idea that current account balances can be explained by the willingness of the countries involved to save (as shown on this page some days ago). Had he done so, however, he would have realised what an intellectual Herculean task lay ahead of him. He would also have realised that it would be impossible to develop a sensible concept with Trump’s libertarian friends and Vice President Vance.

Many also see the US as having an immediate obligation to change. But that is not easy to justify. The economic situation there remains good and much better than in Europe. Talk of national bankruptcy and insolvency emerging in Europe is simplistic and even dangerous nonsense. The government’s new borrowing and total debt are not at levels that would be problematic in any way. In fact, the government could reduce its new borrowing year on year (by a total of around four per cent of GDP) if it managed to reduce and ultimately eliminate the current account deficit.

In the chaotic monetary system in which we live, no one can blame the United States for trying to reduce its huge foreign trade deficits. The appropriate means is a devaluation of the US dollar, which also entails a corresponding real devaluation. If the index level in Figure 2 were to fall to 80, much of the work would be done without affecting the status of the US dollar as an important and widely traded currency and without causing tariff chaos.

However, Trump’s advisers are apparently shying away from this because, as good monetarists, they fear inflationary consequences. Miran writes:

“If the Fed prints dollars to buy foreign currency, it must do something with that foreign currency. It can leave foreign currency at a foreign central bank, but that requires cooperation from that central bank and offers a relatively low yield. Since increasing the money supply is inflationary, doing so imposes a cost on Americans, and using the proceeds to earn low levels of interest at a foreign central bank is not a productive use of funds”.

This is incorrect. Such an invention does not create any inflationary risks. As has been shown many times on this page, inflation has nothing to do with the money supply, however defined. The returns on investing the money obtained through intervention in other countries may be low, but this is money created out of thin air, and any return on it is effectively a gift. Nor is cooperation with other central banks necessary; the central bank can invest the money directly on the capital market, as Switzerland and other countries have done.

Away with bilateralism

Historically, most American administrations and their advisers have suffered from a phobia of multilateralism. America must be able to solve its own problems. This is a mistake. Global currency relations are not a bilateral problem, and currency speculation is one of the main causes of major trade distortions. In order to trade rationally with each other, all countries in the world need a monetary system that ensures that real effective exchange rates remain virtually unchanged. This has enormous political consequences. ‘Competitiveness’, the most important goal of Europe and Germany, must be globally outlawed as a political objective. Only the balancing of inflation differences between countries through systematic and rapid exchange rate adjustments can ensure conditions in international trade that are rational and similar to those in national trade. This would indeed be the core task of a reformed International Monetary Fund.

All countries in the world, not just the US, are called upon to seek economic momentum at home. However, this has consequences that Europeans in particular fear. It may sound paradoxical: because trade can help everyone, but cannot give anyone special treatment, it is important to focus on one’s own capabilities. Cooperation, not confrontation, is essential to this end. In the best case scenario, the current American attempt to use national power to impose its own view of things will be a wake-up call for those who have been brutally exploiting the current non-system for decades and pretending to be the guardians of ‘free trade’ or even a ‘rules-based order’. Germany is at the forefront here.