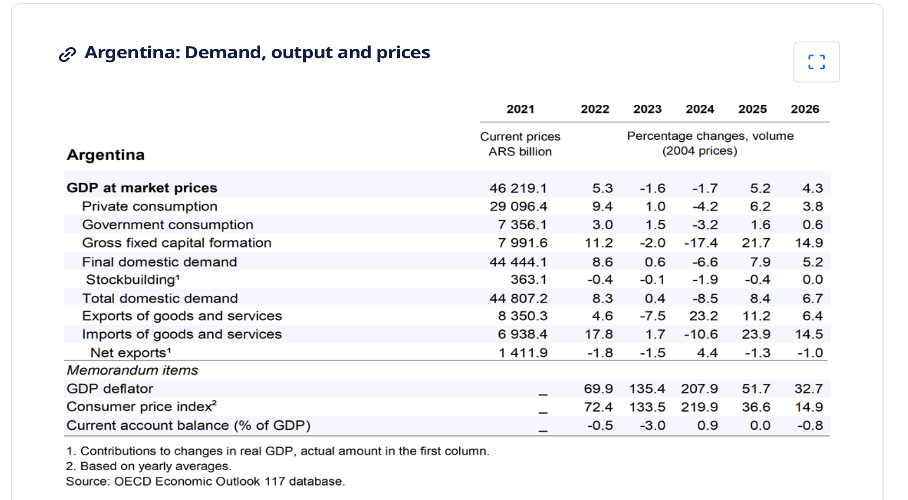

It is not surprising that Argentina’s situation, with its libertarian president, is being hyped by many media outlets. The libertarian-leaning business editors are eagerly waiting to report on the breakthrough of radical ‘liberal’ ideology. However, when a major international organisation such as the OECD allows itself to be drawn into this political game, it becomes annoying. In a report published in June 2025, the organisation writes about Argentina:

“GDP growth is projected to be robust, at 5.2% in 2025 and 4.3% in 2026. Private consumption and investment will continue to recover, sustained by higher real disposable incomes, more favourable financing conditions and an improving business environment. The recent removal of capital restrictions will support further improvements in economic sentiment and investment. Inflation will continue to decline, albeit at a slower pace. Amid rising imports, the current account will deteriorate.”

Higher disposable incomes are therefore the most important driver of growth in the OECD’s view – which is more than astonishing. The accompanying table (see below) shows that private consumption is expected to increase by more than 5 per cent this year and investment by more than 20 per cent. But where does the higher real income of private households in a country like Argentina come from? Why have wages suddenly risen significantly faster than inflation? Were companies unable to pass on wage increases to higher prices this year, even though the economic situation has improved? And if so, what about corporate profits? They must have fallen sharply. But how does that fit in with the massive expansion of investment activity?

The OECD’s analysis becomes even more surprising when one considers the political framework. According to the OECD’s own assessment, policy is consistently restrictive. It writes:

“Monetary policy will need to remain tight to keep inflation on a firmly downward path. Fiscal policy should build on the recent successful adjustment with more sustainable consolidation measures to maintain strong fiscal outcomes. This includes phasing out subsidies and raising public-sector efficiency, while replacing distortionary taxes with broader income and consumption tax bases. Recent efforts to reduce the regulatory burden will boost productivity and should be continued…”

With restrictive monetary policy and restrictive fiscal policy, Argentina is experiencing a strong upturn and an investment boom. Argentina has apparently completely reinvented the art of economic policy. In the US and Europe, monetary policy must trigger a recession if it wants to reduce inflation, because it can only exert sufficient pressure on wages through a decline in investment activity and rising unemployment. In Argentina, however, there are rapidly rising real wages, rapidly rising profits, rapidly rising demand and, at the same time, restrictive monetary policy that is likely to curb inflation. This is obviously complete nonsense. Consequently, the forecasts of 5 per cent growth this year and 4 per cent next year are pure fantasy.

What is the situation?

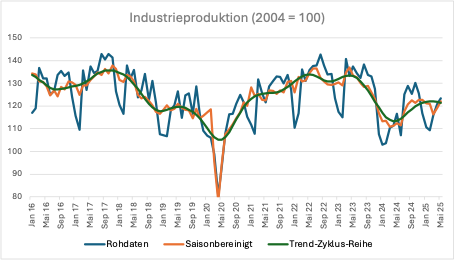

The few reliable facts currently available paint a very different picture. Industrial production (here to be found in Spanish) recovered slightly after a sharp slump in 2024, but is stagnating at a low level (Figure 1). Most recently, in May 2025, it was exactly at the same level as in September 2024. The trend cycle, which adjusts the data for both seasonal and short-term fluctuations, clearly contradicts the existence of an upturn that could simply be extrapolated.

Figure 1: Industrial production index (IPI manufacturero)

Source: Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos (INDEC)

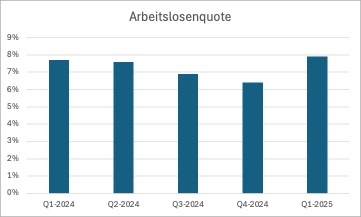

Unemployment is also moving in the opposite direction again. After the decline in unemployment to 6.4 percent in the fourth quarter of 2024 triggered jubilation in the liberal mainstream media and was sold as proof of the ‘success’ of Milei’s radical programme, disillusionment must now set in. The figures for the first quarter of 2025 show a sharp rise to 7.9 percent – the highest level since the pandemic. The labour market report (available in Spanish here) states that the number of people affected by unemployment in Argentina (including the hidden reserve) is around 30 percent of the total workforce.

Figure 2: Unemployment rates in 2024/2025

Source: INDEC

The monetary situation remains extremely difficult. Only negative impulses are to be expected, both from the domestic economy and from foreign trade. According to the Argentine National Bank, short-term nominal interest rates will be around 30 per cent in May 2025, with bank customers having to cope with much higher rates. The inflation rate was 43 per cent in May. This means that, as things stand, real interest rates are close to zero or even negative. This would put an end to the story of restrictive monetary policy. However, if the prevailing expectation is that the inflation rate will continue to fall – the central bank is talking about an expected inflation rate of 20 per cent (we were unable to find out how this was calculated) – then monetary policy is extremely restrictive and a revival of investment is completely impossible.

However, it is obvious that the central bank is doing nothing to actively bring about lower inflation, because to do so it would have had to raise interest rates well above the current inflation rate long ago. This also debunks the widely held myth that the central bank systematically reduces the money supply (the monetary base or central bank money supply) in absolute terms in order to control inflation. In an economy with very strong nominal growth (at 40 per cent inflation!), such as Argentina’s, this is simply not possible without raising interest rates so high that investment activity collapses.

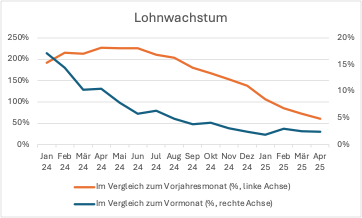

There is now also data on wage developments that clearly shows where the cause of the declining inflation rates can be found (here in Spanish). It is a clear slowdown in wage growth that explains the decline in inflation. Since autumn 2024, nominal wage growth has stabilised month on month at between 2 and 3 per cent (Figure 3). However, wage increases are still significantly higher than in the previous year, most recently at around 72 per cent (March 2025) and 60 per cent (April 2025).

This means that, with an inflation rate of 40 per cent, real incomes have actually risen significantly recently. However, it also means that corporate profits are under enormous pressure. Even if private consumption picks up, there is no prospect of a revival in investment activity.

Figure 3: Growth of Nominal wages 2024/2025

Source: INDEC (year on year: red line, monthly: blue line)

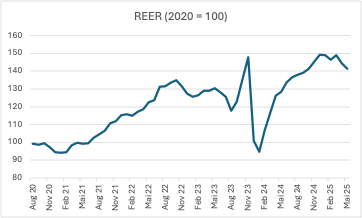

This situation is the direct result of the president’s policy of trying to curb inflation by means of an enormous real appreciation of the peso. The decisive indicator of competitiveness, the real effective exchange rate of the Argentine peso, is at a level that is causing enormous contractionary effects (Figure 4). This is even recognised by the OECD, which (in the table above) forecasts a significant increase in imports (up 24 per cent) compared with exports (up 11 per cent).

Figure 4: Competitiveness (real effective exchange rate)

Source: BIS

The so-called anchor approach (see this article) that Milei wants to implement means that domestic companies will no longer be able to pass on even the reduced wage increases in their prices because competition from abroad is too strong. If they try to keep prices low, they lose their economic substance; if they raise prices to at least break even, they lose market share to foreign competitors on a large scale. In this way, the country is manoeuvring itself into an unsustainable dependence on imports, which sooner or later must end in a major currency crisis.

No solution in sight

It is more than worrying that a large international organisation such as the OECD has allowed itself to be misled into producing a report that contains no serious analysis whatsoever, but instead promotes the widespread prejudices of the libertarian community. There are no easy ways out of Argentina’s predicament. At least, there are none that can be achieved without a U-turn by the state.

The president would have to jump over his own libertarian shadow and work with the trade unions and businesses to find a way to bring inflation down to tolerable levels without permanent restrictions from monetary policy or from imports. Only if deflationary pressure is reduced and Argentina’s competitiveness is restored can the market economy deliver what is expected of it. This cannot be achieved with a chainsaw, but only with a great deal of diplomatic skill and a better (non-libertarian) understanding of the crucial economic interrelationships.