Norway held elections yesterday. However, hardly anyone in Germany and Europe is interested in this, as we know that the country has so much money in reserve (in its sovereign wealth fund) thanks to its rich oil and gas reserves that it no longer needs to worry about the future. But some people believe that the country is suffering from its wealth because it does not know how to proceed after the raw materials boom.

Indeed, there are some astonishing phenomena. A Norwegian colleague pointed out to me that the Norwegian krone has been depreciating in real and nominal terms for years, even though the country is one of the world’s largest current account surplus countries. This is more than surprising. How can it be that such a rich country with such natural trade advantages (as an oil and gas exporter) has such a weak currency?

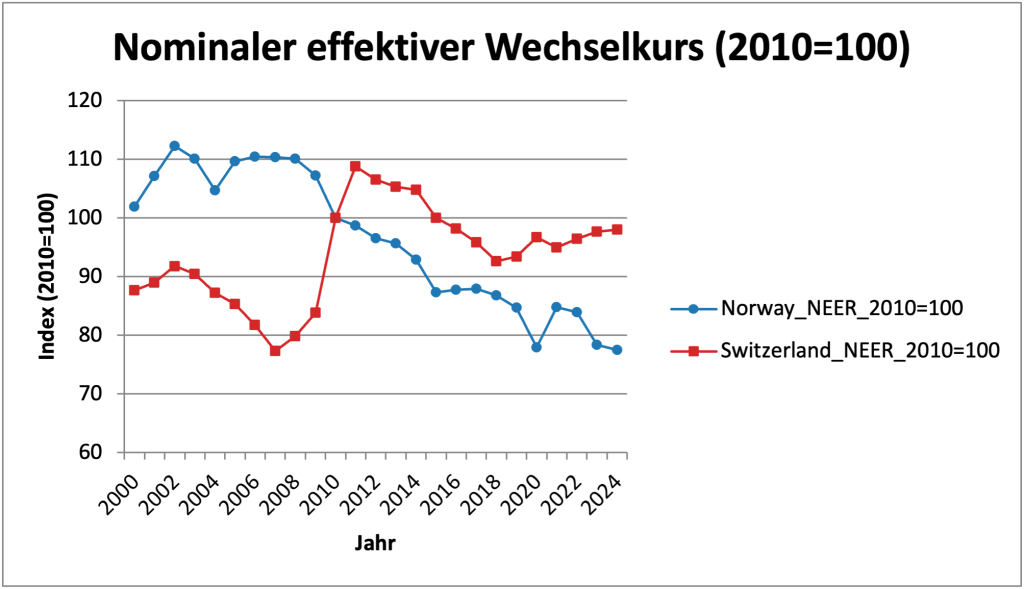

To get an idea of Norway’s currency relations, let’s compare it with Switzerland, another surplus country (also outside the EU), even though the Swiss currency is doing the exact opposite, appreciating in real and nominal terms (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Source: BIS Effective Exchange Rate (broad indices, 2010=100); mirrored via FRED (CCENNR01NOA661N – NOR, CCENNR01CHA661N – CHE). ¹ NEER: nominal² Falling index = devaluation

The Swiss franc experienced a massive nominal appreciation after the global financial crisis of 2008/2009, which the Swiss National Bank countered with varying intensity in order to prevent the appreciation from becoming too strong. In Norway, the krone began to depreciate at around the same time, a trend that has continued to the present day and has resulted in a loss in value of over thirty per cent compared to the years after 2000. In both cases, this is an effective calculation, which means that the change in currency relations with the most important trading partners is weighted and summarised.

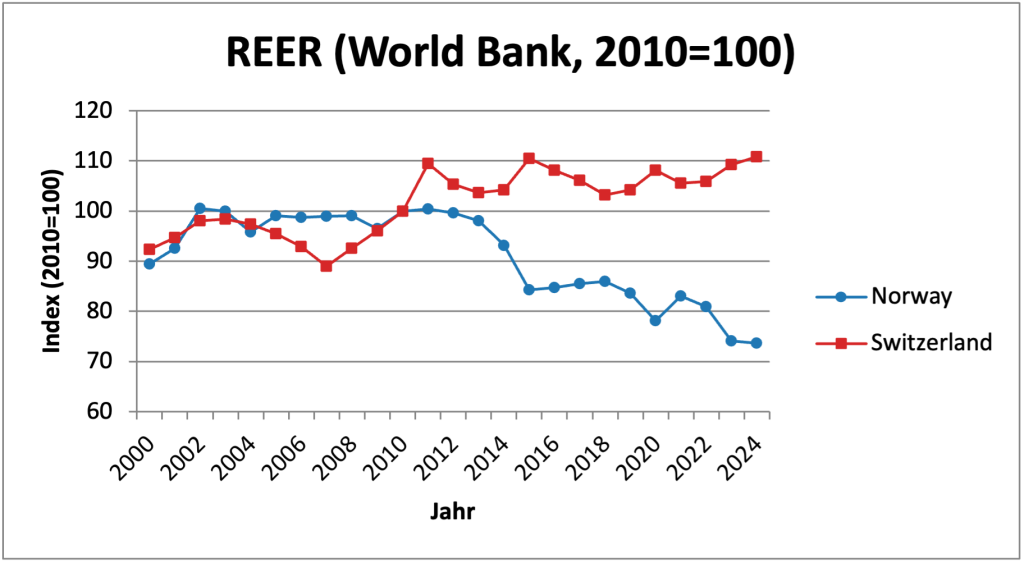

Looking at real effective exchange rates, i.e. the deviations of currency relations from inflation differences, which is the most important measure of a country’s competitiveness, the results are even more astonishing (Figure 2). Switzerland is now appreciating somewhat less significantly after the financial crisis, but the value of the REER remains very high until 2024. The situation is quite different in Norway. Here, the REER began to decline in 2013 and will continue to do so until 2024.

Figure 2

Source: World Bank WDI – PX.REX.REER (Real effective exchange rate index, 2010=100), NOR & CHE. ¹ REER (CPI-based): adjusted for consumer prices. ² A falling index means devaluation.

The Norwegian paradox

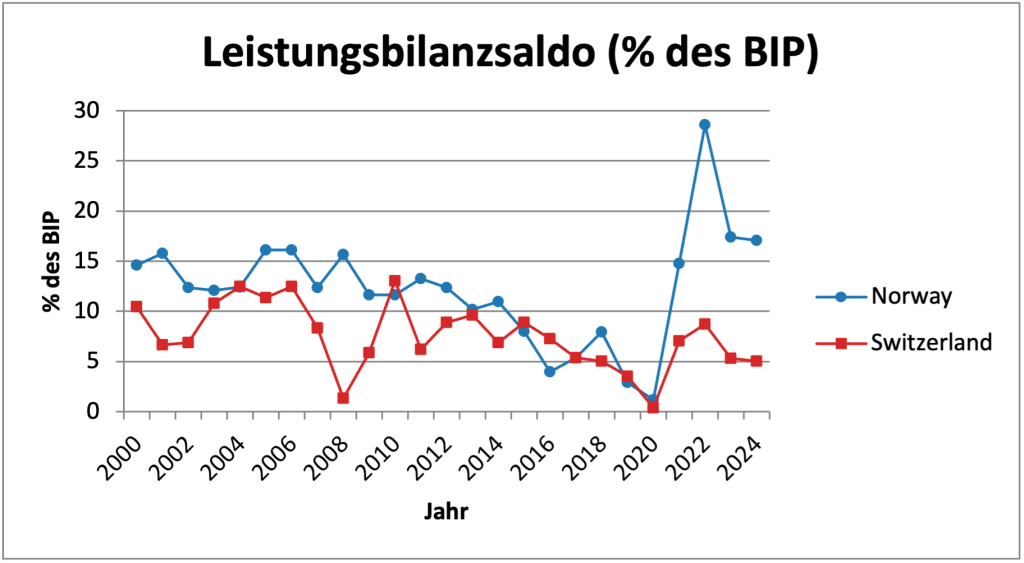

This is impressive: Norway is improving its competitiveness year after year, even though there is no evidence that it has ever lost significant competitiveness before. The current account surplus, which is a (albeit rough) indicator of a country’s external competitive position, was over ten per cent of GDP from 2000 to 2012, which is an enormously high figure (Figure 3). Switzerland’s balance, which is generally considered to be very large, was always below this until 2015.

Figure 3

Source: World Bank WDI – BN.CAB.XOKA.GD.ZS (Current account balance, % of GDP), NOR & CHE. ¹ Positive = surplus; ² Share of nominal GDP.

After 2015, both countries entered a phase in which the surplus declined, reaching almost zero in 2020 (the year of the coronavirus pandemic). However, Switzerland’s surplus then ‘normalised’ relatively quickly, while Norway’s exploded. Since 2022, Norway has become Europe’s largest gas supplier in the wake of the Ukraine conflict. At well over 15 per cent, Norway’s current account surplus is still far beyond what could be considered normal in historical terms.

However, this is by no means consistent with the real depreciation of the Norwegian krone. To find out where the krone’s weakness, which is absolutely baffling from a market economy perspective, comes from, we must first look at the central bank. Is the Norwegian central bank manipulating the exchange rate of the krone against the rest of the world, i.e. intervening in the foreign exchange market to weaken the krone?

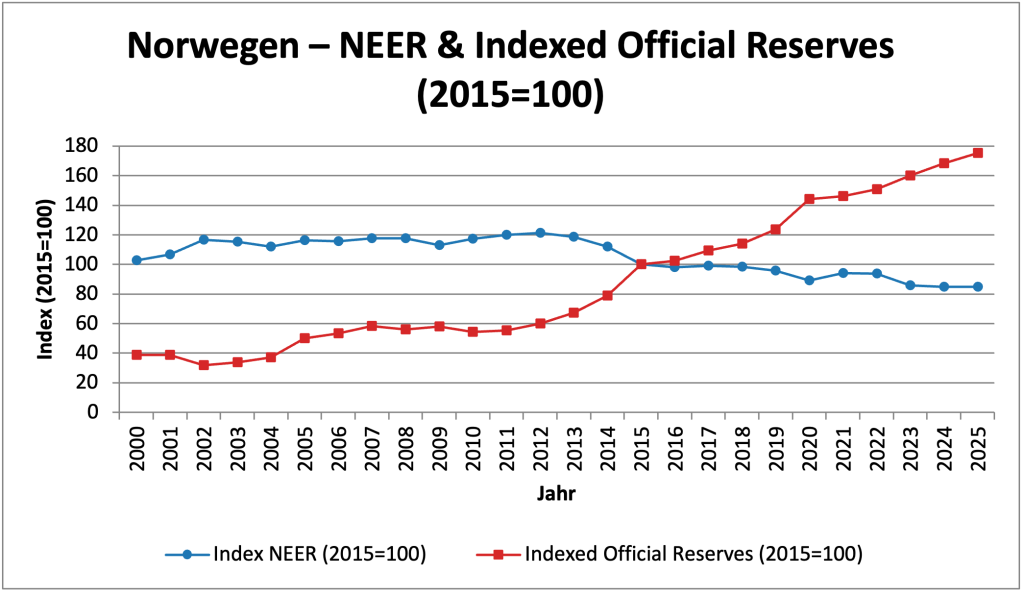

Looking at the NEER, i.e. the nominal effective exchange rate, and the development of foreign exchange reserves, there is much to support the thesis that manipulation is taking place here (Figure 4). The steady increase in foreign exchange reserves since 2012 and the steady decline in the krone’s exchange rate are clearly synchronised and cannot be disputed. The fact that Norway continues to show steadily rising foreign exchange reserves even after 2022, i.e. after the explosion in the current account surplus, is more than astonishing. This is a very strong indication that systematic manipulation is taking place here.

Figure 4

Source: Fed St. Louis and Statistics Norway

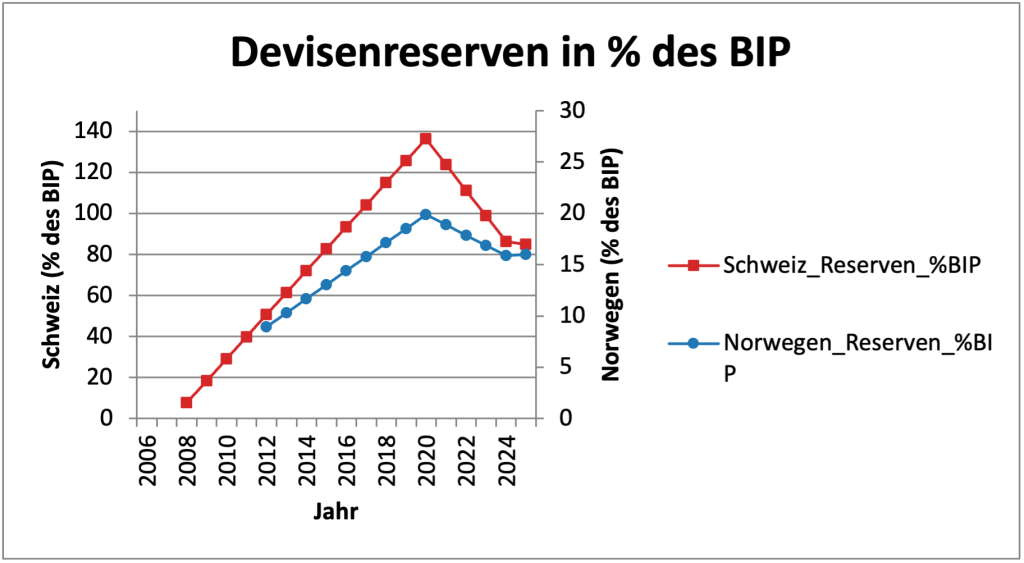

If we compare the development of foreign exchange reserves as a percentage of GDP and compare this again with Switzerland, we see that Switzerland’s intervention was considerably greater in quantitative terms (the scales are very different, so please note the axis applicable to each curve). However, the pressure on the franc to appreciate was enormous, while the krone remained weak throughout (Figure 5).

There is little to suggest that the development of Norway’s foreign exchange reserves can be explained by normal developments on the foreign exchange market. The interaction between a weak krone and rising reserves is too clear. After all, foreign exchange reserves in Norway reached 20 per cent of GDP in 2020, which only appears low in comparison to the absolutely exceptional figure for Switzerland.

Figure 5

Source: World Bank WDI – Indicator FI.RES.TOTL.CD.ZS (Total reserves including gold, % of GDP), countries: Norway (NOR), Switzerland (CHE). ¹ Foreign exchange reserves generally include currency reserves, gold, SDRs and IMF positions.² Values as a percentage of nominal GDP (annual data).

Final remark

The chaos that some people call the international trading system is growing. If a country such as Norway, which is extremely successful in trade and also very wealthy, allows itself to weaken its own currency in order to strengthen its external economic position beyond what it already has, how can a small, poorer country anywhere in the world gain confidence in international agreements?

Real devaluations have just as little place in a rationally organised monetary and trading system as real revaluations. When a rich country systematically devalues its currency, it causes immediate damage to all its trading partners, but especially to developing countries. International bodies, especially the International Monetary Fund, are failing because they play along with the big and powerful countries instead of seeing themselves as advocates for those who need a truly fair and rules-based order.

Such a callous foreign trade policy also undermines the credibility of all proposals made by Western countries to developing countries to adapt to climate change. Norway has largely exploited its fossil fuel reserves without regard for the climate, but now believes that, as a so-called ambitious country, it can put pressure on developing countries to renounce the extraction of fossil fuels. This can never succeed if those who have profited massively do not give up part of their fossil fuel wealth for the benefit of the world’s poorest.

I would like to thank Erik Münster for searching for the data and creating the graphics.