Signs and wonders are happening! The German Handelsblatt has recognised that foreign trade surpluses are not necessarily a good thing. Although they have long been regarded in this country as hard proof of German competitiveness, the paper writes that a country’s surpluses inevitably create deficits in other countries, which can also get into difficulties as a result. Bravo! This is finally a realisation that will help Germany move forward, albeit a good twenty years late.

What’s more, even a leading German media outlet is suddenly admitting that Germany was considered a problem case within the EU. What a happy coincidence that, of all times, the EU is now no longer classifying Germany as a problem case due to excessive trade surpluses for the first time in years. EU Economic Affairs Commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis apparently believes that new government debt will help Germany further reduce its current account surplus. That is why he no longer sees a ‘macroeconomic imbalance’ in Germany. Here, too, is a revolutionary insight that Brussels has preferred to keep to itself until now.

But that’s not all: to underscore its new insight into the situation, Handelsblatt even expects its readers to accept the fact that German companies have become net savers since the turn of the millennium, preferring to build up reserves rather than invest. This is nothing short of revolutionary. German companies are saving, private households are saving, and the state, according to Handelsblatt, has been able to break even for years, i.e. it has also been saving.

Yes, this German savings spree was only possible because Germany was able to force other countries to run up high levels of debt year after year in order to buy German exports. Of course, no one mentions the fact that this simple correlation was hushed up in Germany for 20 years, even though it is obvious. To complete the analysis, it should be added that it was the agenda policy of the red-green coalition, applauded by all parties, that duped the partners in the newly founded European Monetary Union by leading them to believe that wage policy would be aligned with the jointly agreed inflation target. That was a blatant lie.

How do we get out of this?

As always in life, you get out of a mess the same way you got into it, only by taking the opposite measures. In other words, raise wages in Germany, focus everything on domestic demand and give the state the freedom to ensure appropriate macroeconomic momentum by finally abandoning its austerity rules. For Europe, this must mean that all countries are released from the obligation to comply with the Stability Pact, because practically everywhere – as in Germany – companies have become net savers.

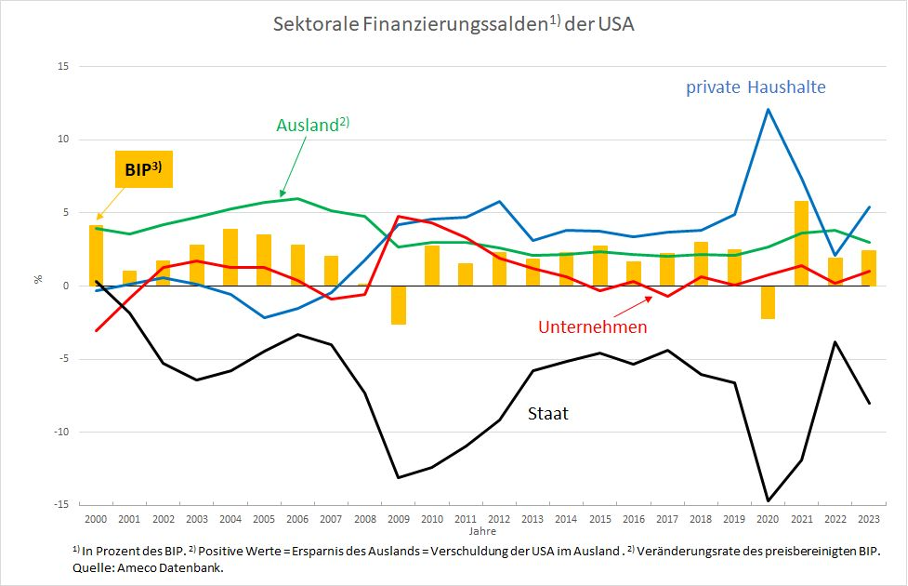

If the German current account surplus disappears, the continent of Europe will find itself in exactly the same situation as the United States, namely confronted with the end of the normal market economy, where companies had systematically taken on the role of debtors. Now, as the figure clearly shows, the state is called upon to act.

If, as in the US, all private balances and the foreign trade balance are positive, logically only the state can save the economy from collapse by taking on debt itself. This can be seen immediately in the graph: whenever the private sectors are uncertain and restrict their spending, as in the coronavirus crisis, but also in the global financial crisis of 2008/2009, the state must intervene immediately and massively, increase its own debt, stimulate demand and thus keep the economy going.

In the United States, this has been impressively successful in the wake of the coronavirus crisis. Donald Trump’s tax bill shows that he will not be deterred by those who have reservations about government debt. And although many individual measures in this bill are extremely problematic in terms of distribution, it will nevertheless lead to a renewed stimulus for the economy without fundamentally calling into question the soundness of American fiscal policy.

A U-turn in Europe is essential

Europe and Germany must now make a decision. However, it is not a question of replacing the global market with the European market for the German economy, but of kick-starting demand across Europe and sustaining it for as long as possible.

The belief that an upturn can also be achieved through deregulation, bureaucracy reduction or even the ‘creation of a genuine capital market union’ (Jens Südekum) is naive. No matter how high the level of regulation, no matter how many trade barriers still exist, the European Union’s economy can only be pulled out of its lethargy by a surge in demand from the state. Because monetary policy, by its own assessment, has already largely exhausted its means and consequently no further major interest rate cuts can be expected, the only option now is government action.

Anyone who wants to credibly move away from exports as the sole driver of the German economy must turn to the European level. But not in the sense of further improving Germany’s competitiveness vis-à-vis its European trading partners, but in the sense of freeing fiscal policy in all European countries from the shackles of the Stability Pact. This ‘pact’ was included in the Maastricht Treaty at the last minute at Germany’s insistence. But it has no place there. If Germany fails to understand that this cardinal error must be corrected as quickly as possible, the German economy will also not be able to escape its slump.