If that isn’t defeat, what is? French Prime Minister François Bayrou asked for the confidence of the National Assembly, and only 194 MPs gave him their confidence, while 364 said no. Just imagine: the head of a sitting government loses a vote of confidence, with almost two-thirds of MPs against him. Apparently, the government lacked legitimacy even before that.

This is what President Macron achieved with his early election last year: France is ungovernable. It is time for the president to face the consequences and pave the way for new elections – preferably including new presidential elections. Starting today, there are supposed to be nationwide protests against Macron, but no one knows whether this will result in mere chaos or whether constructive opportunities will arise. Macron has already been pushed to the brink of open defeat by the yellow vests once before. Perhaps this time the pressure from the streets will be great enough to at least make it clear to him that he has already ruined his presidency and can only cause more damage.

But all those in Germany who are badmouthing their unstable neighbour would do better to keep their mouths shut. Germany is indirectly the main reason why France has become ungovernable. With neighbours like that, who needs enemies (as here already shown after last year’s elections)? But none of the clever German commentators who hold microphones in front of their noses in Paris can understand that. You only have to listen to the interview with Armin Laschet on Deutschlandfunk to understand what utter nonsense is usually spouted here.

France can only escape the European trap if it explicitly opposes Germany and the economic mainstream on the debt issue. Yes, it must emancipate itself politically and intellectually. The whole debate in France, Germany and Europe suffers from the fact that only traditional economics is being discussed. But that offers no solution. According to the augurs of neoclassical economics, France should try to restructure its finances through a massive austerity programme, but that is impossible because it would inevitably and immediately lead to a severe recession. Then the state will once again be particularly challenged because unemployment will rise and social problems will become more acute.

France is in the same situation as the USA (shown here) and must ensure growth in the same way. France would have to engage in an open intellectual battle and explicitly challenge the narrow-mindedness of Germany. But who is to do this in a country where economics does not rank highly in the education of the elite?

However, I do not want to repeat myself. I am attaching excerpts of a paper from April 2024 (by Friederike Spiecker and myself) in which the situation between Germany and France is described in detail and exhaustively.

Ideology beats reason – a new round in the debate on debt brakes and fiscal rules has begun (April 2024)

The fundamental importance of the sectoral balances

Everything that is currently being discussed on the subject of government debt and fiscal rules tacitly assumes that conditions exist in all countries that allow the government to reduce its debt without major economic upheaval, provided that the political will to do so exists. This is wrong. The key question is always who will generate demand if the government increases its revenue or reduces its expenditure. It is pure logic that a country’s public sector can only reduce its revenue deficits, i.e. its new debt, if other sectors such as private households or companies (domestic or foreign) or even the public sector in other countries accept that their expenditure surpluses, i.e. their debts, will increase or their revenue surpluses, i.e. their savings, will decrease. If this condition is not met, any attempt by a country’s public sector to save will lead to a recession in that country and will sooner or later have to be abandoned by the government because it will have to absorb or at least bear the consequences of the recession, for example in the form of increased social security expenditure and reduced tax revenue.

Debt always arises when there is a gap between expenditure and revenue in an economic unit. This is usually due to a real imbalance of such a nature that this economic unit lives beyond its means (i.e. it consumes more real resources than it puts into the cycle) and another lives below its means. For a closed economy or the world as a whole, there can be no living above or below one’s means because real resources can only be distributed and consumed once.

The gap between the income and expenditure of an economic unit is not a problem if there are conditions within an economy (and in the world as a whole) that ensure that the under-the-circumstances living of one group is systematically offset by the over-the-circumstances living of another group. However, there is no systematic balance in the real world that ensures that attempts to save do not automatically lead to a downturn. Neoliberal and neoclassical economists claim that such a balance exists (via interest rates), but this thesis is clearly false, as we have shown theoretically here and as the facts below show empirically.

Typically, in an economy, it is private households that spend less than they earn because they try to provide for the future through this type of saving. The financing balance of the private household sector is therefore regularly positive: there is a constant surplus. Companies would have to counterbalance private households and spend more than they earn because they are the main drivers of investment. Companies invest when they expect to make profits from the investment that will allow them to pay the interest that is usually payable on a loan.

The state does not actually need to incur debt as long as it is certain that the corporate sector will invest at least as much as is saved elsewhere, i.e. that it will fill the spending gap of private households with its own investment demand and correspondingly high debt. In this case, total demand remains unchanged and economic development stagnates. Growth also requires that companies not only offset the surpluses of private households with their own deficits, but that they do even more than that, namely accumulate additional deficits in the form of debt-financed investment demand. The corporate sector must therefore incur more debt overall than corresponds to the surpluses planned by private households.

But this is by no means certain. As the charts in the following section show, companies in many economies, including Germany, are running surpluses, thereby exacerbating the problem of insufficient demand. If the government wants to ensure positive economic development, it must either create conditions that encourage the corporate sector to fully assume its inevitable role as debtor, or it must itself aim for expenditure surpluses, i.e. incur debt.

Foreign countries consist of the same sectors as domestic countries and are therefore in no way suited to being net debtors in the long term in order to fill the gap in a country’s overall demand caused by the domestic sectors’ willingness to save.It should be self-evident that every country in the world has to solve the same problem of private savings behaviour as the domestic sector.

Anyone who is not prepared to take this neutral position cannot present themselves as a serious economist. And economic policymakers who ignore this neutral position should not be surprised if, outside their own country, they encounter at best a lack of understanding and at worst the same kind of economic nationalism – only from the perspective of the other country, i.e. with the signs reversed, so to speak. Incidentally, this has a negative impact on all other areas of international policy where cooperation is so urgently needed, such as climate protection, migration and external security.

Germany is not a role model

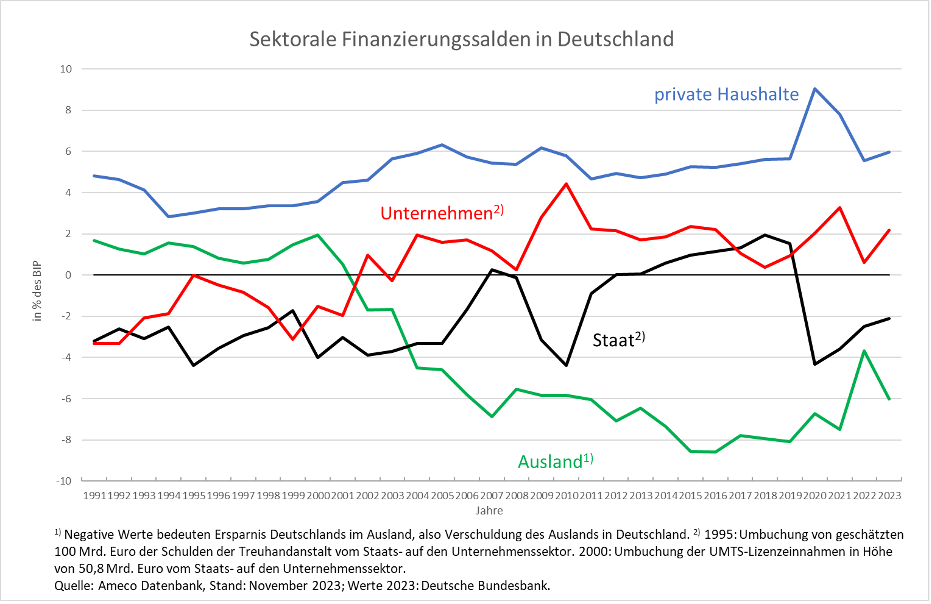

Empirical evidence clearly illustrates the problem. The private household sector in Germany saves around six per cent of GDP (the blue line in Figure 1). Unlike in previous decades, however, German companies have not been doing their part for the last 20 years. Despite massive tax cuts at the beginning of the 2000s, the corporate sector has not contributed to closing the gap between revenue and expenditure, but has instead widened this gap through its own savings in almost every year – the red line in Figure 1 is above zero. This has had a permanent negative impact on the economic development of the national economy (government is black, foreign countries are green).

Figure 1

Parallel to this urge to save on the part of private individuals, the public sector also sought to reduce its deficits or even generate surpluses. Only in response to obviously severe crises such as the financial crisis of 2009 or the coronavirus crisis of 2020/2021 did the public sector allow greater debt. Had it not done so, the economic slump would have been even greater than it already was in both cases. This is because companies responded to the crises by significantly increasing their savings (the red line rises steeply in each case). Private households also resorted to increased savings during the crises, as shown by the respective rise in the savings rate.

The fact that the German economy did not experience a permanent decline as a result of the years of austerity measures in all three domestic sectors is solely due to the annual new foreign debt, which rose to well over six per cent of GDP (the green line in the figure): the excess demand from abroad, based on debt, closed the domestic demand gaps. Germany has saved itself from its savings problem through mercantilism. As we have explained and empirically proven many times, the key to this was undercutting international competition through macroeconomic wage restraint in the monetary union.

France and Italy are suffering from Germany’s obsession with saving

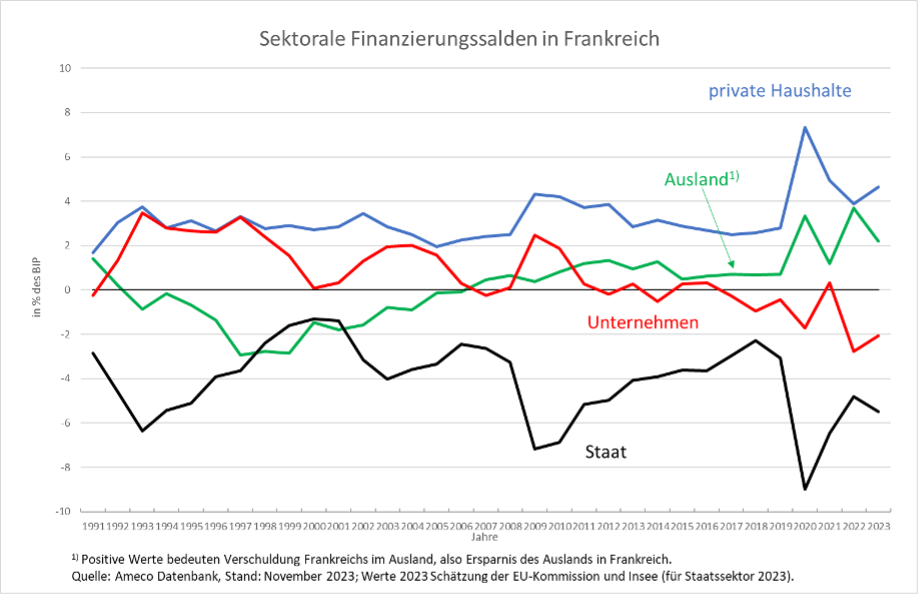

This has had an impact on other countries. For the past 1½ decades, France has recorded a current accountdeficit, albeit a small one in percentage terms relative to its own economic strength: the green line in Figure 2 is above zero, which means that, from France’s perspective, other countries are running surpluses with France. The French private household sector is saving, albeit to a slightly lesser extent than its German counterpart. The corporate sector has been borrowing again for several years, but not to a sufficient extent. In this constellation, the public sector in France had no choice but to borrow if the country wanted to avoid a permanent contraction in its economic output. Anyone who ignores this macroeconomic context when assessing the French government deficit must face the accusation of contributing to the political radicalisation of our neighbouring country. This is because, under the current competitive conditions in international trade, the austerity measures recommended to the public sector can only lead to poorer economic development in France.

Figure 2

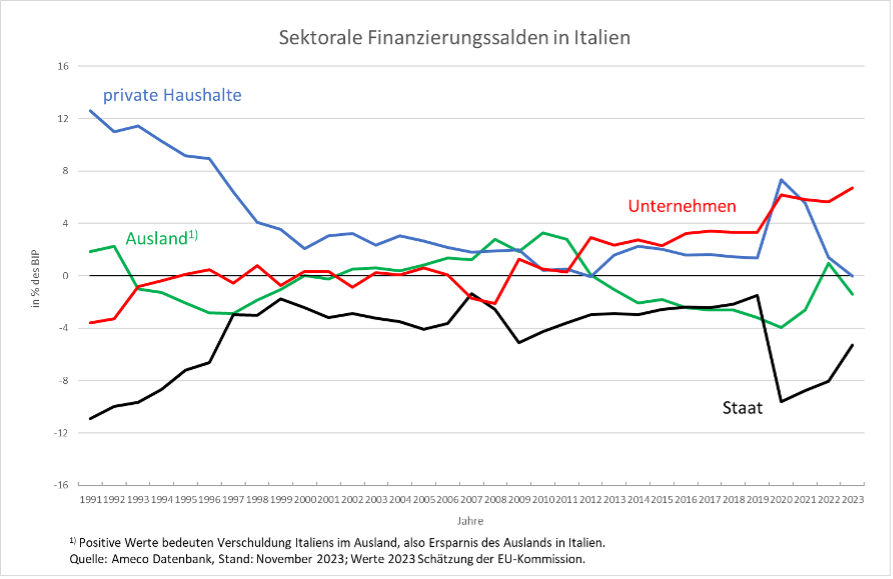

In Italy (see Figure 3), the problem of corporate sector savings is much more pronounced than in France and has even been more serious than in Germany for the past ten years. If private households in Italy were as keen savers as their German counterparts, the domestic savings problem would be even greater. Since the height of the euro crisis, however, Italy has managed to push foreign countries – at least from its point of view – into the role of debtors to some extent by drastically reducing its imports of goods. Nevertheless, the Italian state also had to remain in the role of debtor if it wanted to avoid a prolonged recession, which would otherwise have been the inevitable consequence of private savings.

Figure 3

The logic of the sectoral balances is absolutely compelling, …

These three examples show that it is not possible to meaningfully analyse a country’s public debt without considering the savings and debt behaviour of the other three sectors, especially the foreign sector. Anyone who criticises the public sector’s debt and wants to see it reduced must explain who should take on the debt instead and under what circumstances. On the one hand, it is undeniable that there is always a certain willingness to save among private individuals, which is even more pronounced in times of crisis than in ‘normal’ times. On the other hand, it is also obvious that every country strives to avoid falling into recession or even remaining in it permanently, as is pre-programmed by the saving behaviour of private individuals.

If, in parallel with this private urge to save, every country strives not to incur new public debt or even to reduce old public debt, every country is dependent on other countries, the ‘foreign countries’, to incur debt with it. (It does not matter which of the three domestic sectors of these other countries takes on the spending surplus.) Logically, this cannot work: if no one wants to be a debtor, but everyone wants to be a saver, the economy in all countries will shrink. Economic development cannot happen without debt.

… but is sacrificed on the altar of economic ideologies

Neoliberal economists such as Lars Feld, in the aforementioned study defending the German debt brake, construct a picture that is characterised by the fact that government debt is not considered in relation to the expenditure and revenue of other economic sectors. Germany, like the other countries used for comparison, is viewed as an island that has no relationship with other countries and receives no impetus from them.

In the years examined by Lars Feld, however, the accumulation of an extremely high current account surplus played a decisive role in Germany’s economic development. Only because foreign countries took on the majority of the debt that is essential for growth in any economy was the German government able to reduce its debt without triggering a prolonged recession.

Conversely, this means that the countries with the corresponding necessary current account deficits were not in a position to consolidate their national budgets as well. Unless, of course, their private sector had decided to take on even greater debt in parallel with the current account deficit and government austerity measures. It should be clear to every economic policymaker – with or without a degree in economics – that no private sector in any country in the world is prepared to do this, because government austerity measures and losses in foreign trade destroy any inclination to invest.

The study entitled ‘The debt brake – a guarantee for sustainable fiscal policy’ represents yet another attempt to cloak an ideology in scientific garb, the consequences of which are devastating in both economic and political terms. Because the majority of citizens think in terms of microeconomics, this ideology is much easier to communicate, democratically legitimise and thus implement than anything that even begins to do justice to macroeconomic considerations. And so it is to be feared that German politicians will continue to walk around and act with the ideological blinders offered to them by mainstream economics, both at home and abroad.