It’s already starting: one of Germany’s largest trade unions, the chemical industry union IGBCE, is entering collective bargaining negotiations, which are set to begin in January, without any specific demands. ‘Every job counts, every euro counts,’ says the union, but those who clearly put jobs before euros don’t want more money, they want job security. And job security, according to the pseudo-logic of the unions and business management, means sacrificing wages. Employers have offered a zero increase, and we can already predict the outcome with a high degree of certainty: an agreement of around 1.5 per cent.

At VW in Germany, employees are even facing ‘painful cuts’ because the company is invoking all the clauses agreed in the last collective agreement if the economic situation does not improve significantly. IG Metall will have no choice but to accept real wage losses elsewhere as well. One does not need to be a prophet to predict that the political slogans about ‘excessive labour costs’ in Germany will make all trade unions’ hearts sink. The result will be settlements of no more than two per cent.

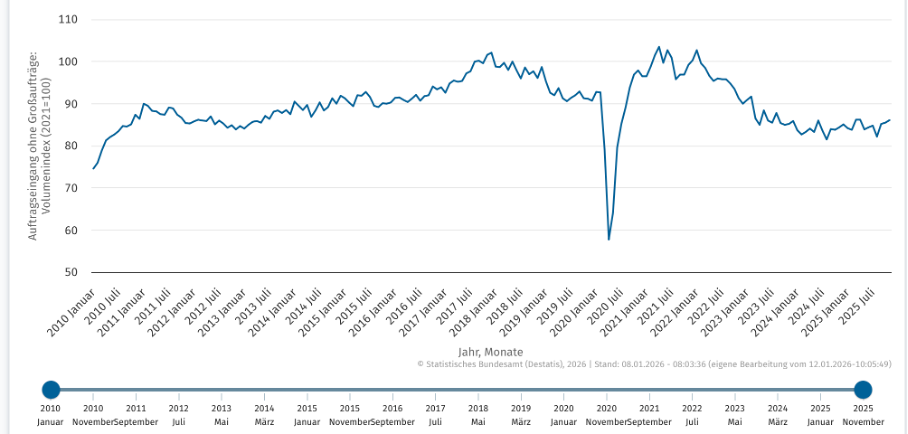

Even after some upward-trending data for November, the economic situation in Germany has not improved (figure from the Federal Statistical Office). Without large orders (from the military sector), total order intake in German industry remains at recession levels. Sentiment indicators even point to another setback in December.

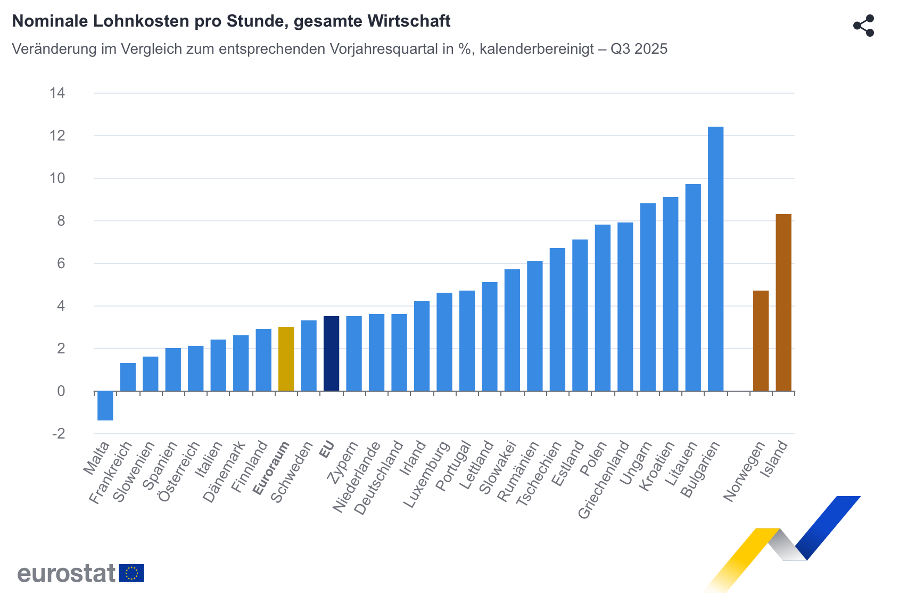

Labour costs in the EMU are rising less

Labour costs across Europe, which rose by 3.3 per cent in the third quarter of 2025 (figure from Eurostat), are rapidly approaching the two per cent mark. It is highly doubtful whether the decline in growth rates will come to an end there. France has been well below two per cent for some time, Spain was exactly at two per cent and Italy only slightly above. If Germany, which was still above three per cent in autumn 2025, falls to two per cent or even below, wages across the eurozone are likely to rise by less than two per cent in the near future.

However, the fact that a country like Bulgaria, which has just become a member of the Eurogroup, recorded a rise in labour costs of over 12 per cent in the third quarter of 2025 is further proof that this country was accepted into the monetary union solely for political reasons. Even producer prices are rising at double-digit rates in the country. The consequences will be dramatic, as recently described here.

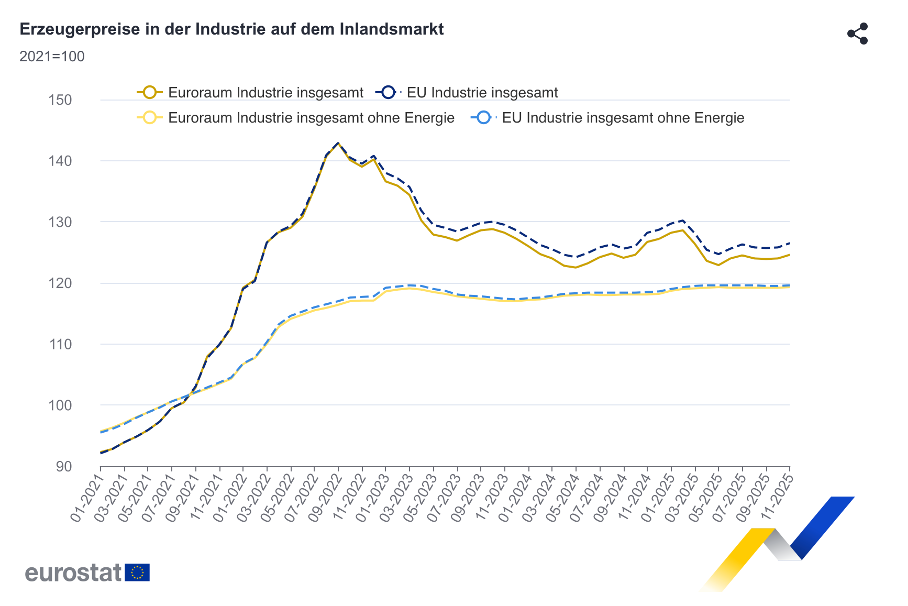

Producer prices as an indicator

If you want to know what happens when wage settlements fall significantly, you only have to look at producer prices in industry in the eurozone. These remained absolutely constant in November 2025 (excluding energy), marking almost three years of absolute stability (figure from Eurostat). The competitive pressure in this sector must be incredibly high if companies there are unable to raise prices by even a millimetre despite the significant wage increases (of four to five per cent per year) over the last three years.

Politicians expect lower wage increases to improve international competitiveness and thus create new jobs – at the expense of other countries. But this calculation will not work out. The only thing that will happen when wage increases in Europe approach the two per cent mark is that there will be even greater pressure on producer prices and thus on consumer prices for all products manufactured with industrial inputs. Producer prices will fall in absolute terms and consumer prices will fall below the two per cent target.

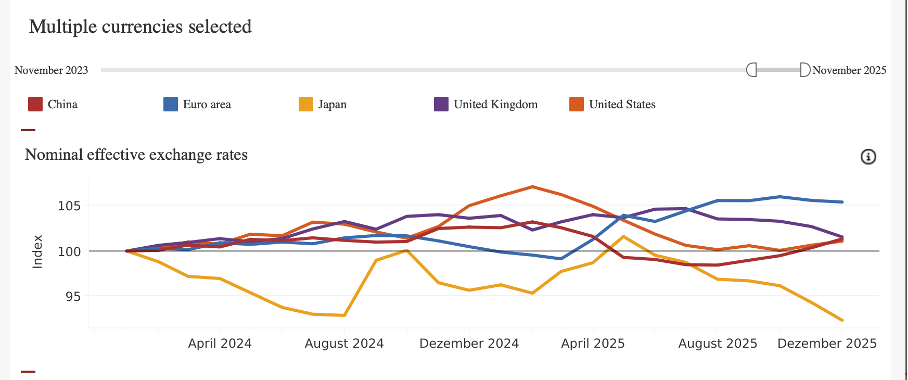

This will have no impact on the international competitiveness of Europe and the EMU because the euro, which has already appreciated significantly against the US dollar in particular since 2025, will strengthen further. In nominal terms, the eurozone has appreciated by around five per cent against a large group of trading partners since the beginning of 2025 (figure from the BIS).

If there is another similar appreciation this year, no amount of wage restraint will be able to offset these losses in competitiveness. Even if there are no further appreciations, the threats by the largest trading partner to raise tariff barriers even further should be reason enough to abandon all hopes of improving competitiveness through relative wage cuts.

What is even more serious is that because the ECB’s leadership is on the wrong track and is considering interest rate hikes instead of cuts, small wage and price increases or even reductions in both would mean a massive deterioration in investment conditions. The real interest rate, which is decisive for investors, rises when prices can no longer be maintained and at the same time the nominal interest rate does not fall or even rises.

The ECB has lost its way

It is easy to show how far the ECB has lost its way. For Executive Board member Isabel Schnabel, the euro economy is on track because current growth exceeds so-called potential growth. However, what many economists refer to as potential growth is the direct result of the weak growth of recent years, which means that she expects the European economy to grow very slightly more than very weakly. With growth forecasts of around 1 per cent for the entire eurozone, no serious person can speak of an ‘economy on track’. The US economy, on the other hand, will grow by around 2 per cent despite several years of full employment.

For Schnabel, the main driver of growth is the ‘robust’ labour market with low unemployment and strong wage growth. Why the labour market in Europe is ‘robust’ with an unemployment rate of over 6 per cent and youth unemployment of almost 15 per cent remains Ms Schnabel’s secret. Her memory apparently only goes back to 1999; she simply does not want to know that Europe once had full employment with rates of around three per cent. Unfortunately, she has failed to note that wage increases in the large EMU countries are currently grinding to a halt.

The most remarkable thing is that she believes the risk with inflation is acceleration, not deceleration. One of the reasons she gives for this is that ‘inflation’ for industrial goods has stabilised at pre-pandemic levels. This is a blatantly false statement; it is not ‘inflation’ that has stabilised, but prices are, as shown above, absolutely stable. Had she correctly talked about prices and not inflation, she would never have been able to make her statement about inflation risks “tilted to the upside”.

Overall, this is a very poor starting point for the German and European economies. Fiscal policy that spends for military equipment but otherwise saves like crazy, monetary policy that fundamentally misunderstands the situation, and the threat of politicians in Germany to pursue a course of wage cuts are a combination that makes any reasonable person shudder.