Readers repeatedly point out that I should take note of the fact that long-term interest rates are currently not following the short-term rates set by the central bank, as I normally assume they do. They point out, for example, that long-term interest rates in Germany are currently tending to rise, while short-term rates have been clearly lowered by the ECB. There is also heated debate at present as to whether the US could be financially ruined if people stop ‘investing’ there or even liquidate investments held there. Caution! Anyone who fails to understand the global interrelationships of the capital markets and the power of the central banks will very quickly get their fingers badly burned.

The relationship between short and long

A longer-term view of the annual averages of the relevant interest rates shows that there is a close relationship between short-term and long-term interest rates in both the EMU and the US. Although the correlation is close, it does not rule out deviations over a period of several months. There have been a few instances in history where central banks have caused confusion, which was misinterpreted by the capital markets and delayed the adjustment of long-term interest rates to short-term rates. In other cases, the capital markets anticipated the actions of the central banks.

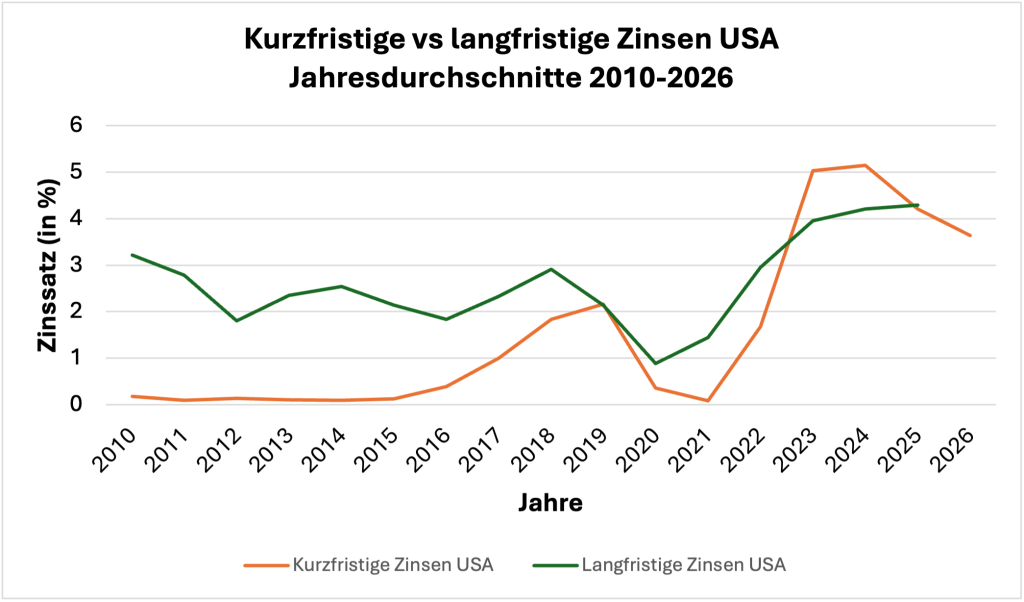

Let’s start with the US (Figure 1). There, too, there have been repeated deviations (such as in 2013 and 2014) in which long-term interest rates did not clearly follow short-term rates, which were almost at zero at the time. In 2014 and 2015, long-term interest rates (green) fell, even though the first upward interest rate move for short-term rates (red) had already taken place in 2016. In 2019 and 2020, long-term interest rates in the US fell sharply because the Fed had already started to lower interest rates again in August 2019. In 2023 and 2024, a so-called inverse yield curve emerged for the annual figures used here, i.e. a situation where short-term interest rates are higher than long-term rates. This is an unmistakable sign of restrictive monetary policy.

Figure 1

Source: Federal Reserve (Effective Federal Funds Rate). Federal Reserve (10-Year Treasury Yield, DGS10). Own calculations. For 2026, we have set the last available point as the annual average for short-term interest rates.

Sometimes the markets anticipate an adjustment in short-term interest rates, as was the case in the US in 2021, even though the Fed did not start raising interest rates again until March 2022. In the last two years, there has also been a clear adjustment of long-term interest rates to the central bank’s guidelines, namely a reduction in politically set interest rates, although the adjustment was not perfect and did not happen immediately. The financial markets have been operating independently for several months, so to speak, but this is mostly driven by speculation about what the central bank will do next. There is no real decoupling.

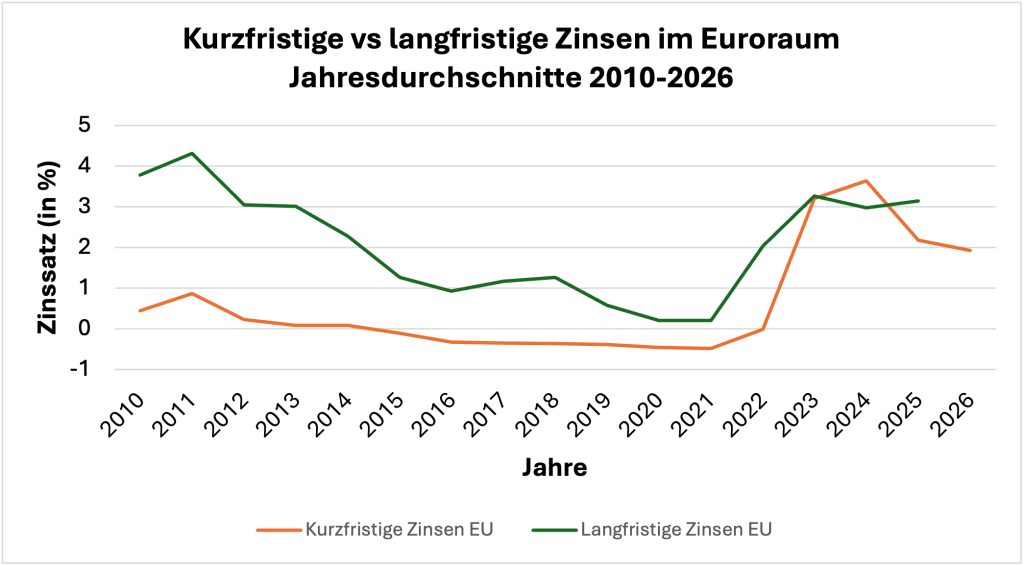

The situation is very similar in the eurozone (Figure 2). Because short-term interest rates (red) remained very stable in the 2010s, long-term interest rates (green) followed short-term rates with a narrowing gap towards zero. It was not until the monetary policy shift in short-term interest rates in 2022 that there was also an upward movement on the long-term side. But the flattening of the rise in short-term rates in 2024 already brought about a downward turn in long-term interest rates. There was also an inversion in Europe because long-term interest rates stopped rising much earlier than short-term rates. The fact that there has been no real decline since then is one of the temporary peculiarities of the capital market that can be observed time and again.

Figure 2

Source: European Central Bank (10-year government bond yields, euro area); Eurostat (IRT_DTD) until 2021; European Central Bank (€STR) from 2022; own calculations. For 2026, we have set the last available point as the annual average for short-term interest rates.

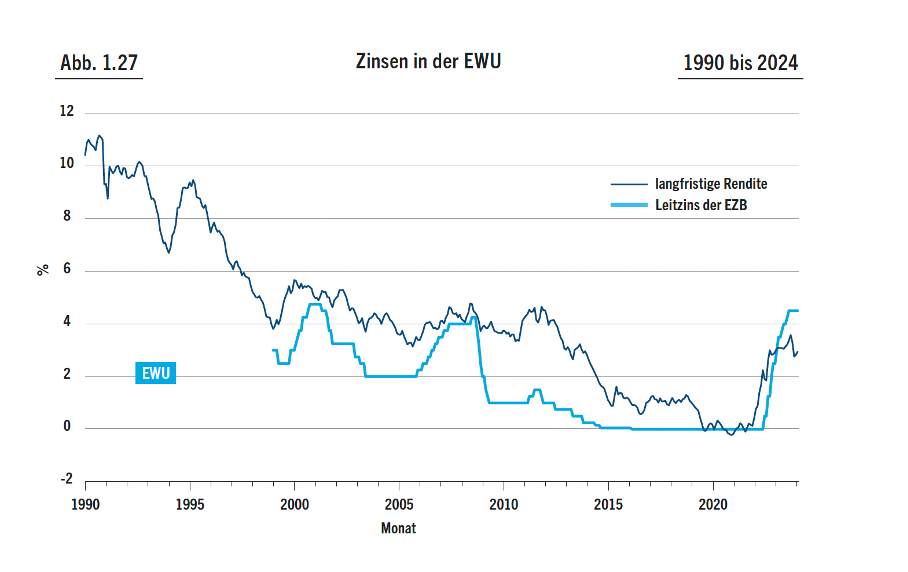

If you look a little more closely than is possible with the annual averages, you can see that even small irritations on the part of the central banks can have a major impact on long-term interest rates (Figure 3, “Leitzins” is short or policy rate). This figure, taken from my textbook (which will come out in English in due course), shows monthly values for the period of EMU. In 2011, there was a small interest rate hike by the ECB, which stemmed from a fundamental misjudgement of economic developments by the ECB (under the then chief economist of the ECB, Jürgen Stark) and which, although it was corrected very quickly, had an enormous impact on the capital market. The downward adjustment of long-term interest rates (“langfristige Rendite”) to reflect short-term developments was delayed by several years because the markets were confused about the direction the central bank had taken and would take in the future.

Figure 3

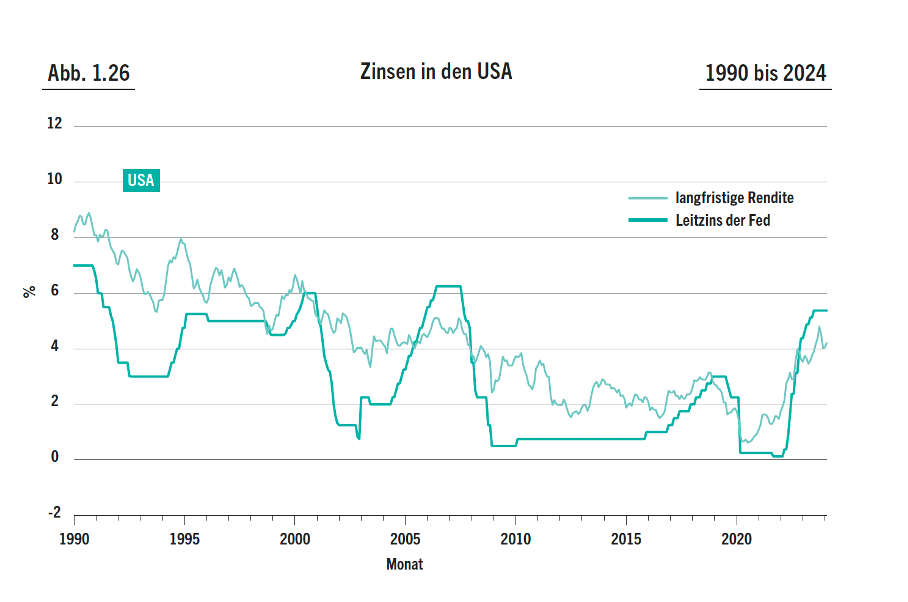

At almost the same time, there was similar confusion in the US when the Federal Reserve raised interest rates once in early 2010, even though there was no reason to do so (Figure 4, also from the textbook). This also delayed the downward adjustment of long-term interest rates for one to two years.

Figure 4

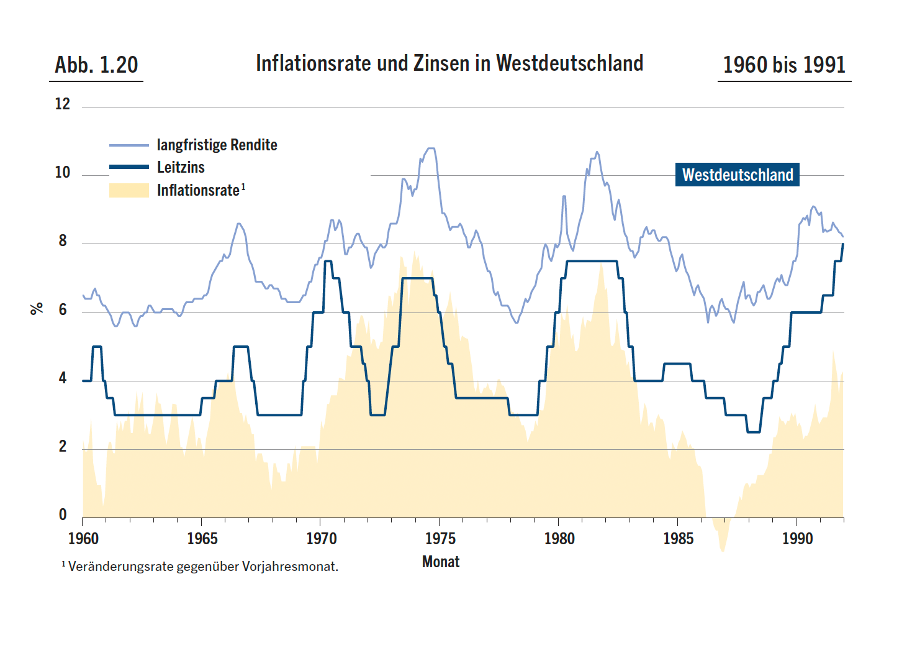

Finally, a graph (also from the textbook) for the years 1960 to 1991 for the Federal Republic of Germany once again clearly shows the correlation. All major interest rate swings by the central bank are also reflected in long-term interest rates. However, the swings on the long side of the market are sometimes larger and sometimes smaller than the central bank interest rate. But that does not change the fact that the central banks clearly set the direction.

Figure 5

There can be no doubt that the central banks also dominate price developments on the capital markets with their instruments. That is why many fears that capital markets are largely autonomous and can, for example, put pressure on countries due to “excessive government debt” are far-fetched or completely irrelevant.

There can be no doubt that the central banks also dominate price developments on the capital markets with their instruments. That is why many fears that capital markets are largely autonomous and can, for example, put pressure on countries due to “excessive government debt” are far-fetched or completely irrelevant.

Can the US be put under pressure on the capital markets?

The power of central banks is currently being completely underestimated in considerations of how to put pressure on the US. Anyone who believes that a reduction in the presence of European creditors in the US would ‘send American interest rates through the roof’ is way off the mark. Nothing would happen because other ‘savers’ would probably take over these securities immediately. However, if interest rates did actually rise, the US Federal Reserve would easily prevent anything from going through the roof by cutting interest rates or intervening directly in the capital market.

Anyone who wants to withdraw ‘their money’ from the US must also consider what impact this would have elsewhere in the world. If interest rates in the US were to go through the roof, they would have to plummet elsewhere. Anyone who wants to ‘withdraw’ should check whether there are other similarly attractive investment opportunities in comparable amounts anywhere else in the world.

Even more important for Europeans: the impact of a ‘withdrawal’, if it could be organised and accomplished (which I do not see happening at all), on currency relations would be enormous. The mass conversion of dollars (which you get for your American bonds when you sell them) into euros would cause the euro to ‘go through the roof’ and possibly ruin European competitiveness for decades to come. If you don’t want that to happen, you have to ensure that the ECB intervenes and prevents an appreciation. But then you’ve shot yourself in the foot. Because then the ECB will hold exactly the same dollars that were previously held by European ‘investors’ in the US. Economically, nothing is gained, but the action would destroy a huge amount of political capital.