Heiner Flassbeck and Erik Münster

People often ask whether Germany’s competitive position has deteriorated in recent years compared to other members of the eurozone, given that nominal wages have risen significantly in this country. Looking at developments from around 2020 onwards, it is clear that Germany has fallen behind Italy and France, for example. However, comparisons based on arbitrarily selected starting years are misleading.

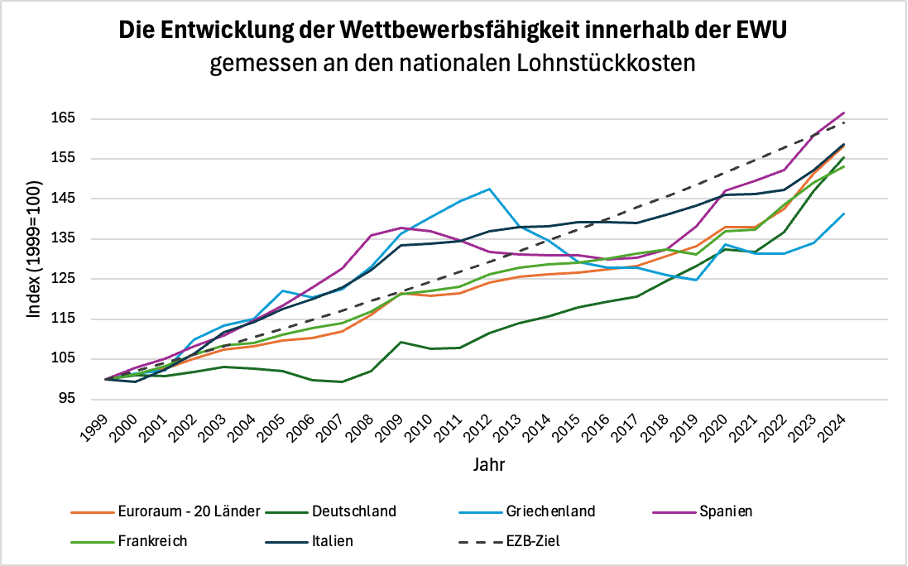

It is always necessary to go back to the start of monetary union, i.e. 1999, in order to capture all deviations in national unit labour costs from the jointly agreed inflation target that have occurred within monetary union. We have therefore updated the graph of the unit labour cost index based on 1999, which we have used repeatedly here, for several countries up to 2024 (unit labour costs are only calculated annually and Eurostat does not yet have data for 2025) (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Now it is important to interpret this graph appropriately. We assume that in the year the monetary union was founded, the deviations between the levels of unit labour costs were small, because the entire convergence process in Europe was aimed at achieving as similar a starting position as possible for all members at the beginning of EMU.

Since we have created an index that reflects all increases and decreases, the annual points on the curves in this graph can be interpreted as the respective level of competitiveness (the observed annual points are connected by a solid line for clarity only). As long as one country’s point is below that of another country, the competitiveness of the country below improves every year. Improved competitiveness in turn means that the country or all companies in the country have cost advantages that they can use to offer their products at lower prices and thus have the opportunity to gain market share over all competitors who cannot offer similarly low prices.

Due to wage increases in recent years, Germany has actually lost some of its lead. In 2024, there was even a reversal of positions with France. For the first time since the EMU was founded, the French curve is now below the German curve, which means that French companies had the opportunity to offer slightly lower prices than German companies for the first time that year. However, given the enormous competitive advantages enjoyed by German companies over the past 25 years, this merely means that a tiny fraction of the market share that France lost to Germany during this period has been regained.

Germany continues to gain competitiveness vis-à-vis Spain and Italy and is able to expand its market share. Only Greece has managed to dip significantly below the German curve since 2021 due to its drastic wage cuts following the major crisis. However, Greece also suffered by far the greatest losses in competitiveness compared to Germany in the early years of EMU.

Conclusion

Anyone who says that Germany has a problem with competitiveness, that labour costs are too high or that we need to tighten our belts is contradicting the facts. Germany is still living below its means and continues to violate the rules of the EMU. Wages would have to rise more sharply than in the rest of the EMU for several years to give the other members a chance to regain at least some of the market share lost to Germany in the past.

However, this will not happen because it is already foreseeable (as shown here) that wage increases in Germany are moving towards two per cent or even below. In some other countries, too, wage agreements are falling below the two per cent mark, which should actually be an absolute lower limit for wage increases in the EMU. As long as Europe’s political leaders insist that improving competitiveness is the most important economic policy concept, the pressure on trade unions will remain unchanged. As has been shown many times on this page, companies are currently unable to raise prices in critical areas, which prompts them to remain tough in collective bargaining negotiations, even when faced with reasonable demands from employees.

Only a revival of demand by the state can resolve this deadlock. A revival of domestic demand across Europe would improve companies’ profit expectations across the board and end the glaring weakness in investment.

Appendix

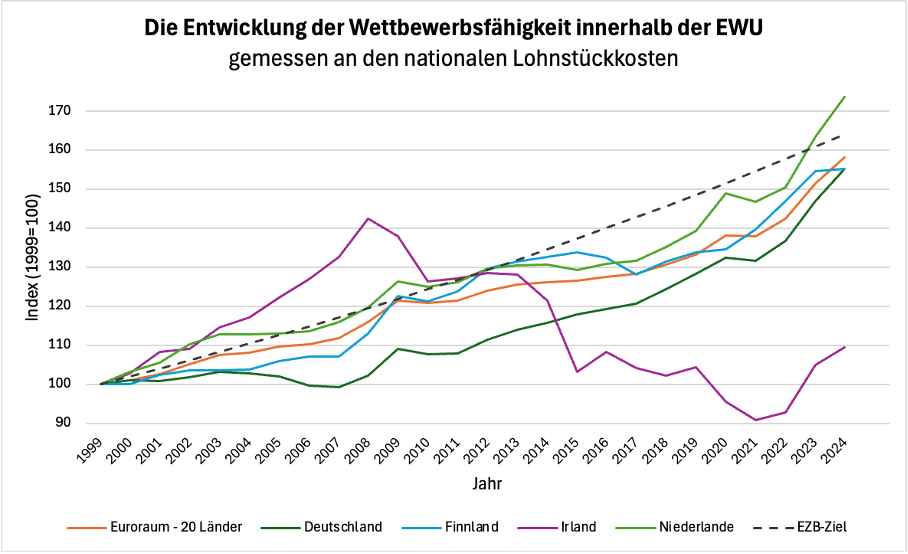

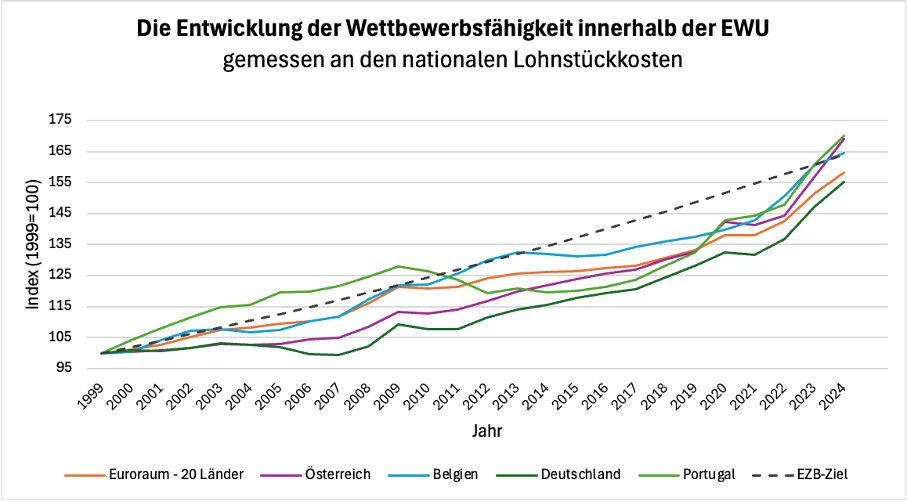

As a service to our readers, we have included figures below showing the development of unit labour costs in the other EMU countries (the founding members) in comparison with Germany and the eurozone as a whole.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Source: Eurostat: Nominal unit labour costs per hour worked; index 1999=100; own calculations