In the exploratory talks in the run-up to coalition negotiations and in their media accompaniment, the state’s debts played a prominent role. In particular, the conservative parties and their media lobbyists feel called upon to warn against a “softening” of the legally established debt rules in Germany and Europe. Europe would be threatened with a debt explosion if Germany, which in their eyes had been the haven of stability up to now, now said goodbye to the noble and traditional principles in the wake of the Corona crisis. Only through growth driven by private enterprise, the conservatives and liberals argue, can public debt be brought back to a tolerable level.

This diagnosis, along with its accompanying therapy, is pure fantasy. It lacks everything: a factual basis and economic logic. It is more than astonishing that it is possible to tell this story over and over again without reaping massive opposition from those who act as experts in the field of economics. This can only be explained by the enormous ideological bias of the so-called economic sciences. Everything that does not fit into their age-old scheme of functioning markets is simply ignored.

It’s a good thing that the crucial relationships are so simple that you can understand them at any time with a little common sense, even without studying economics. This is exactly what we should expect from the negotiating partners in the exploratory talks and coalition negotiations. If the FDP, with its more than naive ideas about government debt, does not meet enlightened partners who can explain the connections to the liberals, any coalition is doomed to fail. Olaf Scholz cannot be expected to be able to do this. Consequently, everything hangs on Robert Habeck, who has at least indicated that he is on the way to questioning the simple prejudices that are not alien to his party either.

In a proper diagnosis of the situation in Germany and Europe, one immediately recognizes that the debt issue is politically crucial. Those who fail here fail in almost all other fields. This applies in particular to Europe, where Germany has to set a new course in the EMU. We must be careful not to fall for short-cuts such as those propagated by SPD chairman Walter-Borjans, who wanted to leave the issue of government debt out of the coalition negotiations because there would not be a two-thirds majority in parliament for amending the debt brake in the Basic Law anyway. Such a position is more than negligent. It shirks the necessary factual debate on an issue that is central to the future of Germany and Europe.

The logical basis

How do debts arise? Debt always arises when there is a gap between expenditure and income in the accounts of an economic unit. Behind this is a real imbalance of the kind that one party lives above its means (i.e., claims more real resources than it puts into circulation) and the other lives below its means .

These gaps between income and expenditure are not problematic if there are conditions in an economy that ensure that the below-the-means-living of one group is systematically balanced by the above-the-means-living of another group. Typically, it is households within an economy that spend less than they earn because they are trying to provide for the future by “saving.” Typically, in the past, it was businesses that spent more than they took in because they invested in the hope of making at least a profit that would allow them to pay the interest that usually had to be paid on a loan.

The government would not actually have to incur debt if it were ensured that companies invested at least as much as they saved, i.e. if they just filled the spending gap of private households. Then, after all, the economy would stagnate. The trouble is that this is by no means the case. Because private households spend less than they earn, companies make losses. After all, the income of private households comes from businesses in the form of labor income (and from the state in the form of labor income and transfer income). The attempt of neoclassical theory to construct a balance here, in which the interest rate on the capital market functions as the decisive link, must be considered a failure and need not be presented again here.

Such an economy is far from a development that could be described as “growth” or “positive change”. After all, growth would mean that companies not only compensate for the surpluses of private households despite their own losses, but that they even do more than that, namely accumulate additional deficits of their own that are higher than the surpluses of private households. If the state wants to achieve growth, it must either aim for spending surpluses itself, i.e. debt, or create conditions that induce the corporate sector to do so.

The foreign sector consists of the same sectors as the domestic sector and is therefore in no way suited to be a debtor or creditor on balance. Indeed, there is no mechanism here, even in traditional economics, that would allow one country to have permanent surpluses and other countries to have permanent deficits.

The Empirical Findings

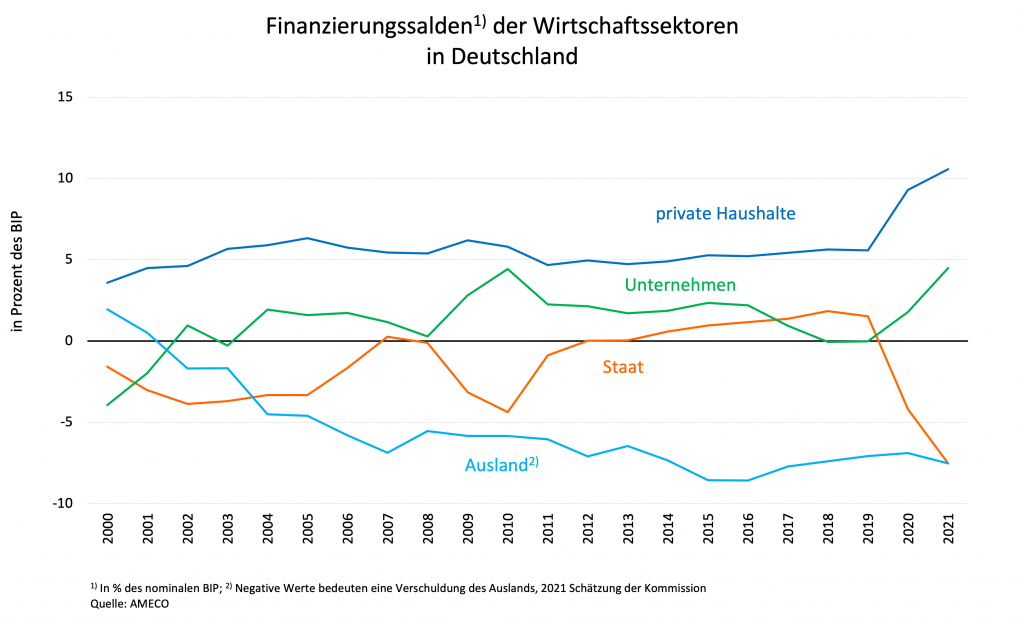

Everything that is currently being discussed is discussed on the assumption that in all countries there are precisely the conditions on the side of the companies that ensure that all other sectors are not forced to accept revenue deficits, i.e. debt. But such conditions have not existed for a long time, as the figure shows.

Figure

For twenty years, the contribution of companies to the economic development of the German economy has no longer been a relief, but a burden. Despite massive tax cuts at the beginning of the 2000s, companies have no longer contributed to closing the gap between revenues and expenditures; instead, they have widened this gap through their own savings in almost all years. Germany saves itself through mercantilism (again, I won’t repeat this because it has been discussed hundreds of times).

In the Corona crisis, businesses and households reacted in a completely similar way, namely by widening their spending gap, which the state had to make up in order to prevent an even far greater crash of the economy. Anyone who expects companies to contribute to growth in this situation must be completely ignorant or a lobbyist for the business community.

In the case of the FAZ, you can take your pick. It writes:

“As finance minister, Lindner will have to balance what is desirable with what is feasible. It’s not just the coalition partners who can thwart him. The debt rule and the budget burdened by the pandemic leave little room for anything new. To generate new growth opportunities, Lindner will have to make almost impossible tax relief possible. This will then benefit not only his FDP, but the entire country.”

Almost more aberrant is what the “business community” itself thinks about this issue, according to a survey in the FAZ:

“The attitude of business experts to tax cuts is interesting. Only 3 percent of those surveyed want them if it meant more government debt. Just under a third want to see tax cuts financed with spending cuts. 17 percent are in favor of a mix of spending cuts and new debt. By contrast, just under half are in favor of foregoing tax cuts if necessary. “As a result, a purely debt-financed tax cut finds virtually no supporters,” EY concludes.”

Tax cuts under the debt rule are just silly stuff. If the government has to recoup the money it needs for the tax cut by cutting spending elsewhere, a tax cut is meaningless in terms of growth and development, no matter who it benefits. The efficiency gains that the FDP hopes will result from a redistribution from the bottom to the top will occur as little in the future as they have in the past. Consequently, for example, “slashing” the social budget in favor of abolishing the solidarity tax remains at best a zero-sum game that increases inequality, but it is likely to be a negative-sum game that also harms the economy.

If you even want to cut taxes for companies, which on balance do the opposite of what they are supposed to do in a functioning market economy, you again must be blind or an ideologue. To say that the whole country benefits from tax cuts from which the FDP profits is pure disinformation from a media that obviously sees itself as a lobbyist.

Anyone who discusses the state’s debts without saying who should make the debts instead, and under what circumstances, if the state does not make them, is basically a charlatan. That so-called economic science allows such charlatans to suggest to people that there can be economic development without debt is by far its greatest failure.